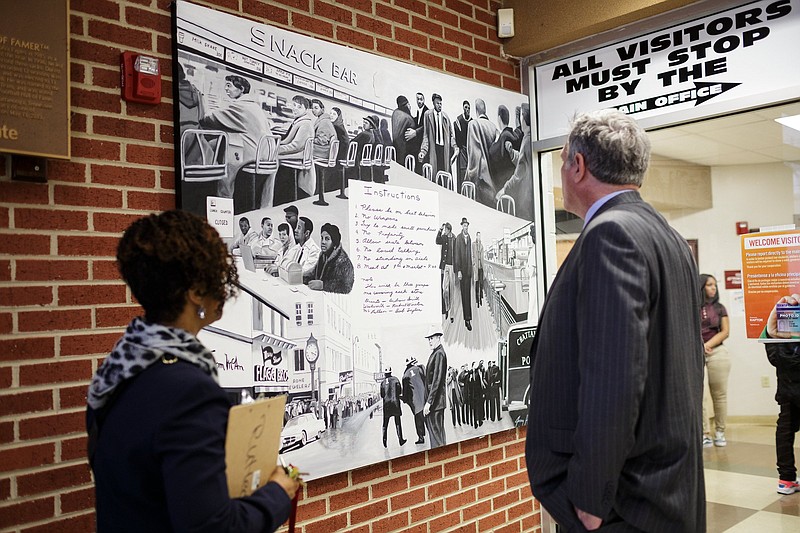

It is especially appropriate in Chattanooga that February nationally is designated Black History Month. For it was in February, 60 years ago this week, that the initial black lunch counter sit-ins in the city - attempting to integrate public and private facilities - reached their peak.

Participants in the sit-ins, which led to the integration of the lunch counters six months later and the end of segregated public facilities about three years later, surely displayed some of the most political courage ever seen in the city. The fact the participants were largely high school students made what they did even more remarkable.

Their actions followed similar attempts by college students in Nashville six days earlier and by college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, less than three weeks earlier.

The initial foray, according to newspaper archives, involved about 30 black students thought to be from Howard High School entering J.W. Woolworth Co., a downtown dime store on Market Street, about 4:15 on a Friday afternoon and sitting quietly at its lunch counter. They were not served in accordance with a 1952 state resolution, which required complete racial segregation in all types of eating establishments, including variety store lunch counters. As such, the lunch counter was closed.

They next went to the adjacent McLellan Co. store, a similar retailer, and sat at its lunch counter, which also immediately closed.

No violence ensued, but attempts the following week saw clashes between police and individuals for and against the integration of the lunch counters. Indeed, police used a fire hose on black and white youths to quell demonstrations. It preceded by more than three years the well-publicized use of fire hoses and police dogs to shut down protests in Birmingham, Alabama, by Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene "Bull" Connor.

The integration attempts by about 200 youths on the Monday following the initial Friday sit-ins occurred at McLellan Co., W.T. Grant Co., F.W. Woolworth Co. and S.H. Kress & Co., all on Market Street.

A reporter's description of the sit-ins said the black youths "read, talked and ate potato chips, peanuts and lunches brought with them," but were not served. Tensions heightened with the presence of white youths who also attempted to occupy the lunch counters, but the appearance of police in the stores prevented any skirmishes.

However, on Tuesday, Feb. 23, 1960, 60 years ago today, newspaper archives described a "near riot between Negro and white teen-agers at a variety store." Accounts said 200 black students from Howard and 300 students from white high schools gathered to contend for seats. After about an hour, in which "flower pots, dishes, water glasses and sugar containers were hurled into the crowd by several of the mob" at one store, did the crowds dissipate. Arrests on minor charges were made of several black and white individuals.

On Wednesday, things grew worse, and a report of the clashes said Chattanooga "became the first major southern city since 1954 to resort to [a] fire hose to clear its main business district of jeering Negroes and whites." Although the lunch counters were closed, eventually "several thousand" people of both races occupied Market Street and slowed rush hour traffic.

At 4:17, according to one account, a hose from the fire engine "Pat Wilcox" was turned on the crowd on first one side of the street and then the other. By the time the crowds began to break up around 5:30 p.m., 14 white and 13 black people were arrested.

No further attempts at sit-ins were made the rest of the week, no more violence occurred, and only a few arrests were made.

The sit-ins resumed in April on two occasions lasting several days and again in May. On these occasions, the incidents were more organized with help - and pickets - from the local NAACP.

Following the February sit-ins and throughout the spring, a biracial committee had been meeting in an attempt to alleviate the situation - and the segregation. Finally, an agreement was reached, and downtown lunch counters were opened to all on Aug. 5.

"The role of every Christian minister and rabbi in any community is that of reconciling God to man and man to man," the Rev. John Bonner, rector at St. Paul's Episcopal Church and a member of the committee, said at the time. "Many ministers, including myself, have tried faithfully to play the role in Chattanooga in recent months."

But the courage of a group of Howard High School students, seeking what few then but many later would call "civil rights," led the way.

Last week, a WalletHub study revealed Tennessee to be the seventh worst state in terms of black participation in elections. Black voter registration was 33rd of the 50 states in the 2016 presidential election, black voter turnout was 39th that year and black voter turnout was 34th in the 2018 midterm election.

Voting is one act of political courage. We hope, as people consider whether to cast a ballot in the March 3 presidential primary or the November election, they'll remember the even more significant political courage of a group of Howard students 60 years ago.