A private business cannot discriminate against an employee because she is white, according to the Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Another one cannot discriminate against an employee because he is a male.

State Rep. Robin Smith, R-Hixson, wants to find out where state law comes down on private businesses mandating that their employees be vaccinated against the COVID-19 virus.

It's a good question and one that deserves a clear and precise answer from Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery.

Smith, who is asking for the legal opinion, said up front that she "can speak firsthand to the effectiveness of the vaccine for our family." But, she said, "I understand the various sides of this argument."

Private businesses have the right to determine many conditions of employment, and the history of this page has long supported them in doing so. But federal and state laws also have curbed some of those conditions over the years, which is likely why the lawmaker is asking.

Elsewhere, the U.S. Justice Department already has weighed in, saying the Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act requires that employees be informed of their "option to accept or refuse administration" of an emergency use vaccine or drug. But it does not prohibit employers from mandating vaccinations as "a condition of employment."

Earlier, the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) had offered guidance that said federal laws prohibiting discrimination in the workplace "do not prevent an employer from requiring all employees physically entering the workplace to be vaccinated for COVID-19."

But the EEOC also said there are cases - medical or religious reasons, for example - where employees might be accommodated through alternative measures such as weekly COVID-19 tests, wearing masks in the office or working remotely.

Smith, though, has couched her question to Slatery about a vaccine being "a condition of employment" through Tennessee's existence as a "right to work" state, meaning its decision that workers do not have to join a union to acquire or keep a job.

She also wondered what legal standing an employee would have if, for some reason, the employee found himself in "an unfavorable, harmful or deadly state of health" from a vaccine, and what legal protections exist for a company if an employee or employees wind up in that state of health.

Complicating the scenario is the state's "at will" status in regard to employment law. While "an employer may not discriminate against any employee on the basis of the employee's race, sex, age, religion, color, national origin, or disability," it "may legally terminate an employee at any time for any reason, or for no reason without incurring legal liability."

This issue is similar though not exactly the same as incidents that have cropped up in recent years in which private employers were asked to make decisions that went against their religion, such as covering the cost of abortifacients for employees or selling wedding cakes to a gay couples.

The United States Supreme Court eventually held - though in very nuanced terms - that employers did not have to provide drugs that induced abortions or cakes to gay couples if it was against their religion.

In this case, though, the mandate involves the introduction into the body of a vaccine that, until just this month (and only in the case of Pfizer) had only been approved for emergency use.

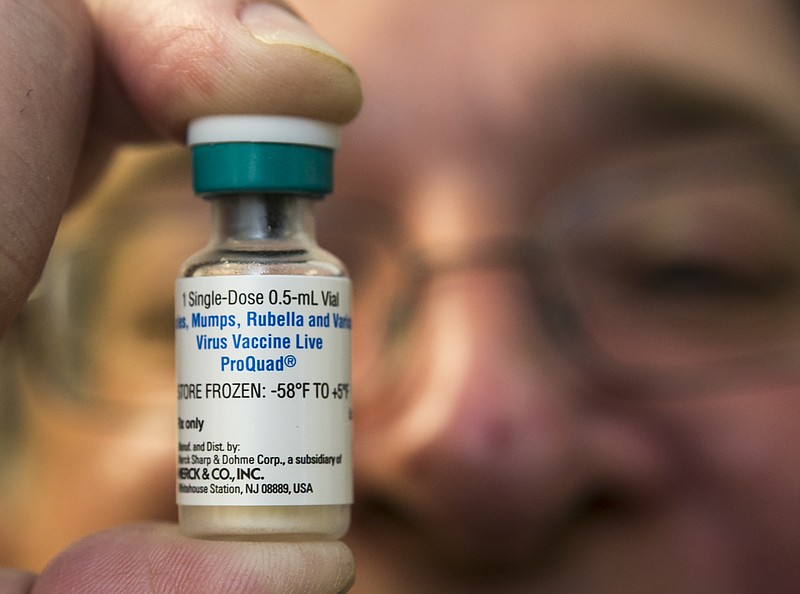

However, requiring vaccines is nothing new for private facilities. A number of states have laws requiring employees in hospitals and nursing homes to be vaccinated against diseases such as measles, mumps and rubella, and a few require such workers to get an annual influenza vaccine.

To be sure, though, all this is relatively new. The first hospital in the nation to make vaccination a condition of employment was Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle in 2004. And though the hospital could report 98% coverage within three years, it still allowed opt-outs for medical and religious reasons.

With the COVID-19 vaccines, a number of states already have vaccine mandates for all state employees (some even add on-site state contractors and volunteers); for state employees only working in state and private health care settings; for all personnel in public and private K-12 schools, public and private higher education institutes and child care facilities; and various combinations of the above.

Individual cities and businesses - New York City municipal workers and new employees at Delta and United Airlines being just a few examples - also are requiring the vaccines. Some, like the city of Chattanooga and Walmart, are offering their employees monetary incentives to get them.

Based on current Tennessee law and recent EEOC guidance, we believe Slatery will come down on the side of supporting what's been called a "soft" private employee mandate with accommodating measures for vaccine alternatives. We believe that is a reasonable compromise that protects both employers and employees.