If you thought masks and mandates would be the only issues Tennessee legislators will discuss in their special session next week, think again.

A bill was introduced Thursday that would permit elections for school boards to be conducted on a partisan basis and allow candidates running for a school board seat to run as representatives of a political party. That legislation is set to be considered in the special session.

Since school boards across the state have been on the front lines over considerations of masks and mandates for students and school personnel, their members' election fits into "the call" (the subject matter) of the special session.

Today, since Hamilton County Board of Education members are the only county office-holders not to be elected with party designations, it makes sense to us to complete the circle.

After all, given the positions of local school board members on various issues and given the contributors to their campaigns, it's usually not difficult to tell with which party they are affiliated.

The bill, as it reads, does not specify whether a representative of a party would be chosen in a primary or if all comers would run together, as in three Republicans, two Democrats and two who do not affiliate with a party in the same election.

The measure, introduced by state Rep. Scott Cepicky, R-Culleoka, says it would take effect July 1, 2022, and apply to school board elections held on or after that date.

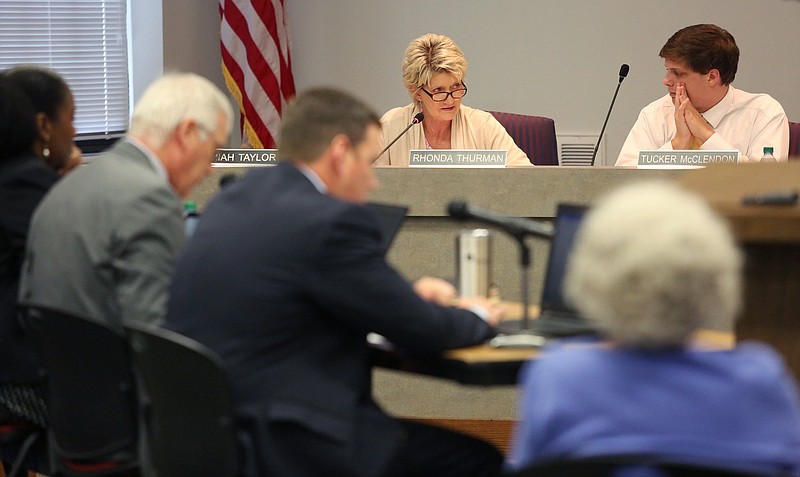

In Hamilton County in August 2022, the school board seats of Joe Smith (District 3), Karitsa Mosley Jones (District 5), Jenny Hill (District 6), Tucker McClendon (District 8) and James Walker (District 9) normally would be up for election. But the apple cart of 2022 local elections is being upset by the redistricting process currently underway and by the decision earlier this week by Hamilton County Mayor Jim Coppinger not to run for re-election.

Currently, the Hamilton County Commission is pondering an 11-district panel in its redistricting process. That would likely mean the school board would have the same 11 districts, but talk in early redistricting workshops was that a parallel school board was not a given.

A joint county commission-school board meeting on Tuesday may provide some clarity on that issue.

Hill, who was elected to the Chattanooga City Council in April, already has said she will not be running for re-election to the school board. Coppinger's decision not to run leaves the field for county mayor wide open. If District 3 County Commissioner Greg Martin and District 8 County Commissioner Tim Boyd run for the position in the Republican primary, we could envision Smith and McClendon, respectively, running for their seats.

Smith, for his part, ran as an independent against Martin in the special election to fill the unexpired term of Marty Haynes, after Haynes was elected assessor of property in 2016.

In the current county commission set-up, Republicans outnumber Democrats by a 6-3 margin on the panel. If all current school board members suddenly were forced to declare a party, the split likely would be five Republicans and four Democrats.

The one difference would be in District 2, where County Commissioner Chip Baker is a Republican, but Marco Perez was elected to the nonpartisan school board in 2020 with the strong backing of the area's top traditional donors to Democratic candidates.

But as we read Cepicky's bill, if it were to pass, school board elections "may" be partisan, and candidates "may" but would not have to "campaign as the nominee or representative of a political party."

If that is the case, Hamilton County officials could decide to keep the elections nonpartisan.

We can see advantages and disadvantages to this approach.

On the plus side, declaring a party affiliation would force candidates to be honest about who they are and embrace those who are backing them. And if the county commissioner and the school board member run in the same party it could forge a better working relationship between the two, particularly if they worked together to be elected.

On the minus side, one would think the subject of public education should be neutral, impartial and an issue that crossed party lines. So a partisan election might invite more tribalism, coarsen the dialogue, and highlight differences rather than agreements.

Unfortunately, with the leftward tilt to public education over the last 60 years, that ship has sailed. Conservatives concerned with public education today often fight a losing battle just to be heard.

Most states still elect their local school boards in nonpartisan elections, but public sentiment has been changing on that issue in recent years. A 2017 Tennessee bill to allow for partisan school board elections in counties with more than 100,000 people failed, but other states are pondering the change.

The way we see it, with the current lay of the land, the elections may as well be partisan now. They're everything but partisan in name as it is.