One of the funniest stories I ever heard about the college admissions madness came from an independent consultant who was paid handsomely to guide families through it and increase the odds that Harvard or Yale said yes.

He recounted the involvement of one father and mother in their son's personal (hah!) essay, which they didn't trust him to ace himself. They drafted it, focusing of course on the hardship that he had overcome. But when they showed it to him, he spotted a minor problem. What they'd described - his mom's difficult pregnancy, a sequence of visits to medical specialists, so much fear - predated his arrival in this world. Poignant as it was, he could take zero credit for it.

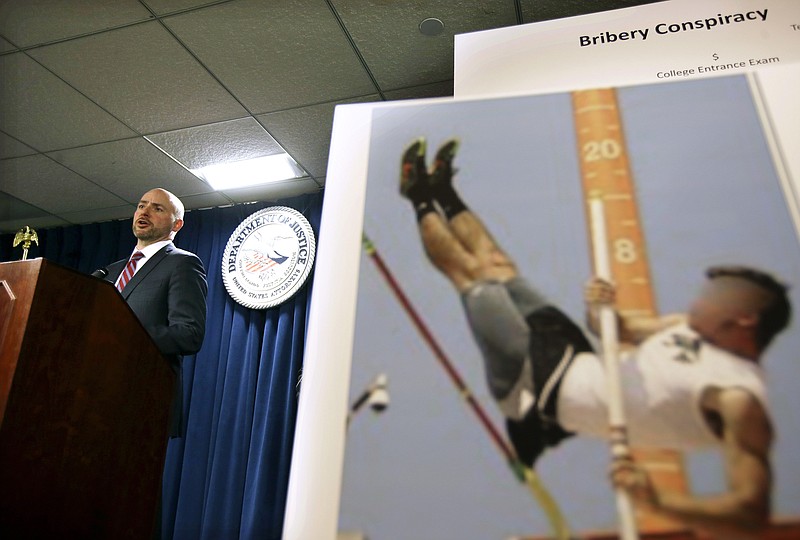

On Tuesday, the Justice Department announced the indictments of dozens of wealthy parents for employing various forms of bribery and fraud to get their kids into highly selective schools. Some allegedly paid college coaches, including at Yale and Stanford, to lie and say their children were special recruits for sports the kids didn't even play. Others allegedly paid exam administrators to let someone smarter take tests for their children. Millions of dollars changed hands.

It's a galling exposé of widespread cheating by families who are already well-to-do and well-connected, but it's not really a surprising one. Anyone who knows anything about the cutthroat competition for precious spots at top-tier schools realizes how ugly and unfair it can be: how many corners are cut, how many schemes are hatched, how big a role money plays, how many advantages privilege can buy.

The wrinkle here is that the schemes were actually criminal and will apparently be prosecuted. But they're versions of routine favor trading and favoritism that have long corrupted the admissions process, leeching merit from the equation.

It may be legal to pledge $2.5 million to Harvard just as your son is applying - which is what Jared Kushner's father did for him - and illegal to bribe a coach to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars, but how much of a difference is there, really? Both elevate money over accomplishment. Both are ways of cutting in line.

It may be legal to give $50,000 to a private consultant who massages your child's transcript and perfumes your child's essays, and illegal to pay someone for a patently fictive test score, but aren't both exercises in deception reserved for those who can afford them?

What a message it sends to the children: You're not good enough to do this on your own. You needn't be. Your parents and your counselors know the rules, and when and how to break them. Just sit back and let entitlement run its course.

The Jared Kushner story was uncovered more than a decade ago by Daniel Golden, who showcased it in his 2006 book, "The Price of Admission," a definitive account of the strings pulled by rich families like Kushner's. Jared did get into Harvard, despite grades and test scores that were, according to Golden's reporting, well below what Harvard typically wants.

I spoke with Golden just after the Justice Department detailed the bribery and fraud scam, which he characterized as "an extreme outgrowth of what I wrote about."

"I had a chapter about how the wealthy benefit from athletic preference because there are so many white patrician sports that most kids never get a chance to play," he said. Inner-city schools aren't sending as many rowers or water polo players to the Ivy League as the storied boarding schools of New England.

They got away with it, the Justice Department charges, because coaches went along with it, accepting bribes. The people indicted by federal prosecutors or implicated in what happened worked at Wake Forest, the University of Southern California, Georgetown, UCLA and other prestigious schools. According to court documents, the former head coach of the women's soccer team at Yale pleaded guilty almost a year ago and became a cooperating witness who helped federal prosecutors gather evidence against others.

There are many takeaways from this appalling story. One is how crassly hypocritical parents can be. I bet that more than a few of those charged are proud liberals who talked about the importance of equal opportunity and an even playing field, then went out and did whatever it took to push their kids into the winner's circle.

While colleges pledge fairer admissions and more diverse student bodies, they don't patrol what's going on with nearly enough earnestness and energy to honor that promise.

The spell that some of these colleges cast over applicants and their families - and the magic attributed to them - are absurd. But they are indeed part of an infrastructure of perks and packaging that isn't uniformly accessible.

When struggling Americans seethe at "the elite," they mean parents who exploit their station to try to guarantee it for their kids. They mean the self-regarding colleges that allow that to happen.

When they say the system is rigged, they have this kind of wrongdoing - and the widely accepted and entirely legal shenanigans that are none too far from it - in mind. Our country's best schools are supposed to be engines of social mobility and the gateways to dreams. Sometimes they're just another sour deal.

The New York Times