Let's hope Santa and his elves and reindeer are good swimmers and won't mind a greener Arctic landscape.

This just in from the "Capital Weather Gang" at The Washington Post: "The Arctic is undergoing a profound, rapid and unmitigated shift into a new climate state, one that is greener, features far less ice and emits greenhouse gas emissions from melting permafrost, according to a major new federal assessment of the region released Tuesday."

The new assessment is the 2019 Arctic Report Card, a major federal look at climate change trends and impacts in the Arctic, the largely (for now) ice-covered region at the northernmost top of our world.

The Arctic is so vast that it includes parts of Russia, Canada, United States (the northern swath of Alaska), Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Finland, Sweden and Iceland. And the North Pole is to the Arctic as Ross's Landing is to our country's Southeast.

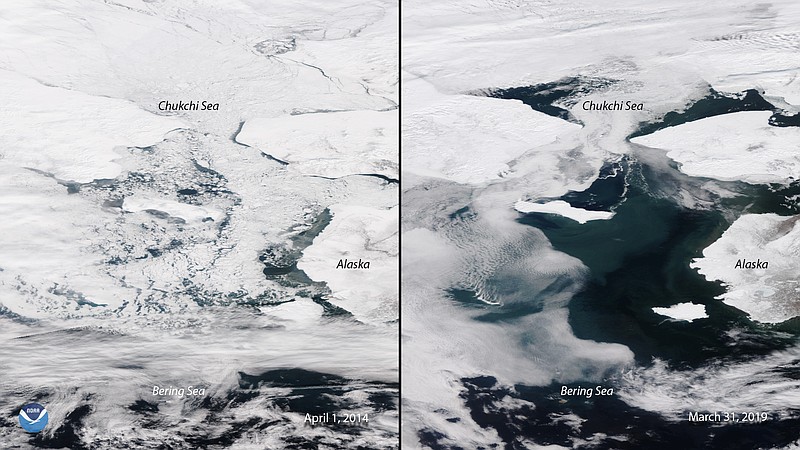

But according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, there's no land at the North Pole; it's all ice that's floating on top of the Arctic Ocean. And over the past four decades, scientists have seen a steep decline in both the amount and thickness of Arctic sea ice during both summer and winter months.

How do they know? Each year, data and photographs from satellites - even in the Arctic's months of total darkness - help NOAA ice analysts estimate the thickness and state of Arctic ice. Multi-year ice is thicker and has survived at least one melt season, while first-year ice is much thinner. Arctic sea ice usually reaches its minimum around mid-September each year. In 2018, the National Snow and Ice Data Center noted that the amount of multi-year ice remaining that summer was the sixth lowest on record, according to NOAA.

Then came 2019. Rick Thoman, a climate specialist for the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, has noted that 2019 had the lowest - lowest - ice extent on record.

The problem with this "new normal," as NOAA describes it, is that it won't just affect Santa's North Pole.

The 2019 Arctic Report Card paints an ominous picture of the Arctic region speeding to an entirely new and unfamiliar environment. The report says the consequences of the climate shift will be felt far outside the Arctic in the form of altered weather patterns, increased greenhouse gas emissions and rising sea levels from the melting Greenland ice sheet and mountain glaciers.

The report concludes that the Arctic already may have become a net emitter of planet-warming carbon emissions due to thawing permafrost - the carbon-rich frozen soil that covers almost a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere's land mass - primarily in Alaska, Canada, Siberia and Greenland.

And, yes, the effects will feed each other as the permafrost carbon release accelerates global warming.

Need some perspective? Scientists say that the 1,460 billion to 1,600 billion metric tons of organic carbon stored in frozen Arctic soils is almost double the amount of greenhouse gases already contained in the earth's atmosphere. That organic carbon really needs to stay there - frozen in ice. But we have just tripped over the tipping point.

Ted Schuur, a researcher at Northern Arizona University and author of the report card's permafrost chapter, told the Capital Weather Gang that the new study, combined with other recent scientific work, indicates that "we've turned this corner for Arctic carbon" and "the feedback to accelerating climate change may already be underway."

LEARN MORE

› See the 2019 Arctic Report Card at https://tinyurl.com/tra99mc.› Learn about the North Pole at https://tinyurl.com/rkrm6vh.

The 2019 Arctic Report Card concludes that these permafrost ecosystems already could be releasing as much as 1.1 billion to 2.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year - almost as much as the annual emissions of Japan and Russia in 2018, respectively.

On the other hand, that's not as much as it may seem. Schuur told The Washington Post that those Arctic emissions are less than 10% of fossil fuel emissions each year: "So it's a small addition to what humans are already producing."

Still, he said, the Arctic number is likely to grow with time as the region continues to warm.

"We've crossed the zero line," he said. "We don't think the Arctic is going to emit so much more emissions that it will make fossil fuel emissions irrelevant," but any extra emissions complicate the already difficult task of slashing them to net zero by mid-century to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

If earthlings don't get our act together, Santa may need a sea-going schooner and eight tiny dolphins. We may, too.