House Speaker Nancy Pelosi this week will again sharpen the focus on the impeachment of President Donald Trump. And on the future of our democracy.

On Friday she alerted her colleagues that she will transmit articles of impeachment against Trump to the Senate and prompt a trial there over charges that the president abused his office and obstructed Congress.

Once those articles are transmitted, the Senate's third impeachment trial of a sitting president in American history should begin promptly. That means possibly as soon as Wednesday.

The House impeached Trump on Dec. 18 in a largely party-line vote charging him in connection with a thoroughly Trump-like scheme to pressure the new president of Ukraine to publicly announce an investigation of Trump's top election rival - Joe Biden.

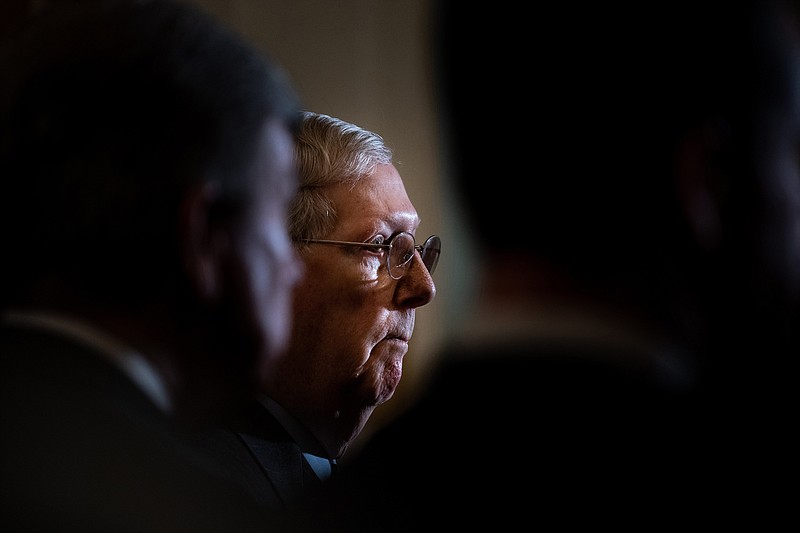

But when some of the most Trumpish of senators, including Senate Leader Mitch McConnell, began making it clear that they'd already made up their minds to support Trump, Pelosi said she'd hold off on the transmittal until she knew the trial rules - like who the witnesses, if there were any, would be. That would determine, she explained, what kind of managers she would need: questioners or orators.

(More: Pelosi to send impeachment to Senate for historic trial)

On Friday, Pelosi in her announcement wrote: "In an impeachment trial, every senator takes an oath to 'do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws.' Every senator now faces a choice: to be loyal to the president or the Constitution."

Pelosi's delay was strategic - and intuitive. As the world waited, new evidence and documents surfaced, including emails showing more of the administration's internal deliberations over Trump's actions. Former White House national security adviser John Bolton announced he would be willing to appear if a subpoena were sent. Moreover, public opinion had gradually inched up in favor of both Trump's removal from office and in favor (57%) of the Senate allowing new witnesses and testimony. Additionally, 86% told FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos impeachment tracker that senators should attempt to be impartial jurors examining the evidence rather than be guided by their party (10%) on how to vote.

Now with Pelosi's decision, the ball moves to McConnell's court.

Imagine, for just a moment, that you are eagerly awaiting the trial of a person who had tried to force you to testify falsely against your neighbor or lose your long-promised pension. Imagine that the judge (or judges, if the case were on appeal) had already told all of the reporters in town that they were working with the extortionist and didn't want to hear from you or any other witnesses. Would you feel you were about to get fair justice? Of course not.

That's a reasonable analogy of what Mitch McConnell and too many U.S. senators - including our own Sen. Marsha Blackburn - have shamefully done. Doesn't that already seem to place them in violation of the oath of impartiality they will take later this week as the jurors in Trump's impeachment trial?

Lawrence Lessig, a professor at Harvard Law School, thinks so, and he reminded Americans recently in a Washington Post op-ed that the impartiality oath our senators must take before this impeachment trial is mandated by the Constitution. It's very language, set by Senate rules, requires each senator to swear to "do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws."

Lessig writes: "To swear a false oath is perjury - the crime President Bill Clinton was charged with in his impeachment. Yet given the Constitution's speech or debate clause, a senator likely could not be charged with perjury for swearing falsely on the Senate floor. Instead, it is the Senate itself that must police members' oaths - as it has in the past."

(More: Analysis: Pelosi's delay tests public opinion on impeachment)

Don't hold your breath on that one. The same McConnell who openly said last month that he would shape the trial "in total coordination with the White House counsel," designing it to minimize the damage to Trump and arrive at an acquittal as quickly as possible, also said he can get 50 of his Republican colleagues to agree to what amounts to an unfair, no-witnesses trial.

And, no, he won't care how many Americans or editorial pages or political pundits criticize him. After all, did he care about criticism when he refused for about year to bring to the floor President Obama's Supreme Court Justice nomination of Merrick Garland?

Lessig contends that the real question will fall to Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., who will preside over the president's trial: Can Roberts accept an oath that he knows is false? Can he seat a juror who he knows has pledged not to be impartial? Lessig says Roberts should forbid McConnell from taking the oath, and thus forbid him from taking a seat as a juror.

Time will tell. If that drama unfolds, the decision could be appealed to the Senate as a whole, Lessig says. And should the Senate openly accept a false oath - perjury, the thing for which Clinton had to be impeached - that would make any senator who allowed it "a party to that falsehood."

If that's not sobering enough, consider this warning that Lessig offers us - and our senators - "A nation governed by the rule of law cannot accept a plain flouting of the law."

This should be an interesting week.