Carter Godwin Woodson is given much of the credit for Black History Month.

Who? Don't know that name? Well, there is so much that so many of us don't know about Black history. Beginning with the fact that Black history is American history.

And that's exactly what Woodson thought. It's why the American historian, author and journalist in 1915 founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Disturbed that history textbooks largely ignored America's Black population, Woodson took on the challenge of writing Black Americans into the nation's history.

It's also why, in February 1926, he launched the celebration of "Negro History Week," which became the precursor of Black History Month.

Born in Virginia in 1875, the son of former slaves, Woodson spent his childhood working in coal mines and quarries. His only early education was a yearly four-month term that was customary for Black schools at the time. He was 19 before he was finally allowed to enter high school, but having already taught himself English fundamentals and arithmetic, Woodson completed the four-year curriculum in two years. He went on to earn his bachelor of literature degree from Berea College in Kentucky, a master's degree in history from the University of Chicago and a doctorate from Harvard.

Woodson believed "the achievements of the Negro properly set forth will crown him as a factor in early human progress and a maker of modern civilization."

He was right, of course, but that didn't stop the flagship history professionals of the time in the American Historical Association from ignoring him. Things are only slightly better today.

We should lament the fact we rely on a calendar designation for "Black History Month." Do we have a White History Month? But what is most lamentable is that we still are not a culture inclusive enough to see ourselves as President Barack Obama once intoned: not a white America, not a Black America, but a United States of America.

Woodson saw this, and it made him something of a self-proclaimed "radical." In March of 1915, he proposed to the then-6-year-old NAACP: Secure an office for a center to which people may report whatever concerns the Black race may have," and boycott, or has he put it, urge "diverting patronage from business establishments which do not treat races alike."

Charles E. Cobb Jr., in his book, "On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail," wrote that then-NAACP President Archibald Grimke "wasn't enthusiastic about the idea."

The rejection prompted Woodson to write to Grimke, "I am not afraid of being sued by white businessmen. In fact, I should welcome such a lawsuit. It would do the cause much good. Let us banish fear. We have been in this mental state for three centuries. I am a radical. I am ready to act, if I can find brave men to help me."

Finding brave men to help, it seems, is always hard.

Woodson chose the second week of February for his early celebration of Black history because it marked the birthdays of two men who greatly influenced the Black American population: Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery and became an abolitionist and civil rights leader, and President Abraham Lincoln, who signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which abolished slavery in America's Confederate states.

Chattanooga has an ample share of important Black history.

We can read some of it - and walk it - with Chattanooga history buff and attorney Maury Nicely's book titled, "Chattanooga Walking Tour and Historic Guide."

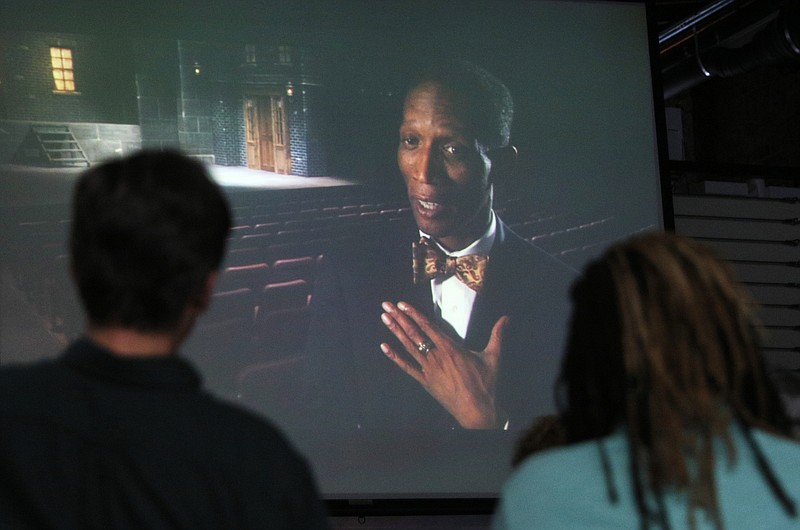

We can watch some of it starting Thursday on WUTC's Scenic Roots six-part series on the Ed Johnson Project, the story of a Black man hanged by a mob on the Walnut Street Bridge in 1906. Besides being one of our nation's thousands of horrific tragedies of racial terror, it also is the story of several historic firsts: Noah Parden, a local attorney, was one of the first Black attorneys to argue before the Supreme Court, which issued a stay of Johnson's execution. After the illegal mob lynching, the Supreme Court conducted a criminal trial for the first and only time. The landmark Supreme Court case set a precedent for federal oversight of local civil rights that was used throughout the Civil Rights era and still today.

To learn about Black history nationally, visit www.africanamericanhistorymonth.gov.

For his work, Woodson has been called the father of Black History, but he probably wouldn't like that.

"We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history," Woodson once wrote. "What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice."

That would indeed be a great history. Let's start today.