NASHVILLE - A Nashville judge ruled Friday that school districts in Hamilton and six nearby counties can proceed with their lawsuit over Tennessee's funding of public education.

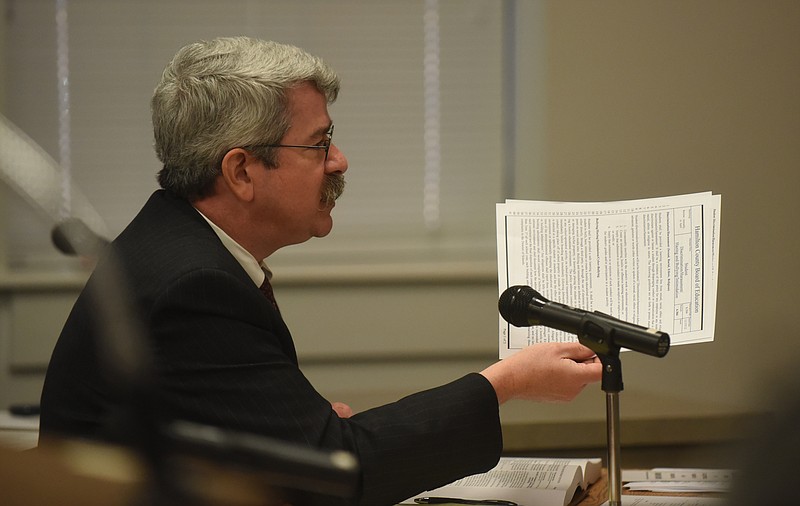

"I am respectfully denying the [state's] motion to dismiss," Chancellor Claudia C. Bonnyman said after hearing nearly 90 minutes of arguments from state Deputy Attorney General Kevin Steiling and Hamilton County Board of Education attorney Scott Bennett.

But the state wrested one victory out of the hearing when Bonnyman denied Hamilton County's motion for class-action status in the lawsuit over the state's Basic Education Program funding formula.

If granted, the motion would have brought all 141 school systems into the lawsuit.

Even so, Friday's ruling opens the latest chapter in a nearly 30-year legal struggle over state support of public education.

Small school systems won three cases in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, charging that state funding was not equitable among districts.

The new suit questions whether the BEP formula is adequate given what the counties call insufficient state support.

In effect, Hamilton, Bradley, Polk, McMinn, Grundy, Marion and Coffee counties argue state funding must rise before the pie can be divided equitably. If the districts win in court, Tennessee government could easily be required to spend at least a half-billion dollars more each year to make things right.

"I'm not surprised that she denied the motion to dismiss," said Bennett, attorney for the six systems.

"The law on this issue is very clear," he added. The latest claim "is simply a continuation" of the earlier struggle.

Because the state hasn't significantly boosted its share of the actual cost of hiring teachers since 2002, he said, "it's hardly surprising we're where we are."

He said Bonnyman's denial of class-action certification "doesn't really bother us" and noted the chancellor herself spoke of the administrative burden of a class action.

In the midst of the court discussion over the class-action issue, attorney and former state senator Roy Herron asked to speak on behalf of the 80 small school systems in the original funding suit.Herron said the systems aren't interested in joining the new suit now; they're waiting to see what Republican Gov. Bill Haslam and the GOP-led General Assembly do on K-12 funding in Haslam's proposed budget. He also didn't rule out the systems filing their own lawsuit.

Shelby County, Tennessee's largest school system, filed a separate suit, saying its huge numbers of low-income children make its situation unique. The Tennessean reported Williamson County, one of Tennessee's wealthiest, may be looking at a lawsuit.

The BEP provides billions of dollars to local systems, which add to the pot based on their ability to pay. Haslam put nearly $250 million in new money into the funding formula of his proposed 2016-2017 budget.

But Haslam also wants to eliminate an equalization provision in the formula that favors urban systems like Hamilton County's.

Steiling, the deputy attorney general, argued at the hearing against the suit's four basic claims.

One is that the state is failing its duty under the Tennessee Constitution to "provide for the maintenance, support and eligibility standards of a system of free public schools."

"The small schools cases really don't provide a lot of support for the adequacy of funding," Steiling said, suggesting the claim would stake new legal ground because the Tennessee Supreme Court steered clear of the adequacy issue in its 1990s and early 2000s rulings on in those cases.

The "facts don't support that level of constitutional funding," Steiling added.

He questioned claims that the current formula and funding amounts violate equal protection rights, run afoul of state law on funding adequacy and constitute unfunded mandates on local systems.

State law says education support is "subject to available funds," Steiling said, because officials knew "there would be lean years" when tax revenues did not support expansion.

While the formula says the state will put up 75 percent of school funds and locals 25 percent, the current 70 percent state level is permissible because of the "available funds" provision, Steiling said. He referred to it as "sort of an escape clause."

Asked Chancellor Bonnyman: "Does it really mean, as written, '75 percent as we can?'"

Yes, Steiling said.

But Bennett responded: "The bottom line is that for more than 20 years, the General Assembly has breached its responsibility to provide substantially equal" funding.

In the second and third small schools cases, the Supreme Court in effect "blessed" the BEP, which was created in response to the first suit, he said. But the court also noted the formula "failed to address teachers."

It still doesn't, Bennett said. And that's forced school systems to cut back on needs from school supplies to computers to provide their share of formula expenses for teachers.

Twenty years ago, the court found the teacher funding shortfall was $3,800 per year per teacher, he said. By now, it's $10,000 per teacher, a $534 million-a-year gap, Bennett said.

The state also has ignored years of recommended formula improvements by the BEP Review Committee, he said.

The end result is funding disparity between and within school districts across the state that affects students, he said.

As an example, Bennett cited differences in ACT scores between Signal Mountain High School, located in a wealthy community, and The Howard School, in a low-income area of Chattanooga.

Signal Mountain parents can afford to pay fees and charges for things like science lab equipment, but Howard parents can't, he said.

When Bonnyman said the hearing's aim was to defend criticisms of allegations in the complaint, Bennett said his illustrations were a "fundamental point" in the case.

"You don't start having a discussion about equity until you address adequacy," Bennett said. He contended the state was "artfully focused on school systems" when the real argument is over unequal treatment of students within districts across Tennessee. And that comes back to equal protection, he added.

"It's not fair to these families to have to pay fees if they want their children to have high ACT scores," he said.

It's "nothing to do with counties," Bennett added, but "everything to do with equal opportunity. Those kids can't pay for it and it's not fair."

Contact Andy Sher at asher@timesfreepress.com, 615-255-0550 or follow via twitter at AndySher1.