TUSCALOOSA, Ala. - Wilbur Jackson and John Mitchell already had their place in University of Alabama football history. Now the Crimson Tide's first Black players also share a prominent spot outside Bryant-Denny Stadium.

The university unveiled a plaque honoring Jackson and Mitchell in a ceremony before the Tide's A-Day spring game on Saturday, more than 50 years after they broke the program's color barrier.

"It was a moment I will never forget," said Mitchell, who had become emotional when he spoke at the ceremony. "It was very touching. You grow up a little Black kid from south Alabama, and these are things you never dream of. "

The two 70-year-olds, who played for Paul "Bear" Bryant, were also honored at halftime.

The introverted Jackson became the Tide's first Black scholarship football player when he signed on Dec. 13, 1969. In 1971, Mitchell became the first Black player to appear in a game for Alabama.

Mitchell, a defensive end who transferred from Eastern Arizona Junior College, wound up starting all 24 games over two seasons at Alabama and earned All-Southeastern Conference recognition both years. Soon after that, he returned to his alma mater as the program's first Black assistant coach. He has been on staff with the NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers since the mid-1990s, currently as their assistant head coach.

Jackson became a star running back for Alabama, the only school to offer him a scholarship. He was a first-round NFL draft pick in 1974 by the San Francisco 49ers, where he played five seasons before spending three more in the league with Washington.

"If somebody had told me when I was 18 or 19 years old that 50 years later we would be here today being recognized for integration, I would never have believed it," Jackson said. "And yet here we are."

Both are members of the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

Tide coach Nick Saban showed his team a video of Jackson and Mitchell last year, the 50th anniversary of Mitchell's first season on the field.

"These guys were people who did something that nobody else was really willing to do that created so many opportunities and changed lives of so many people and changed the mindset of a lot of other people and was a big step in desegregating the South," Saban said. "And I think Coach Bryant should be commended for what he did to make that happen."

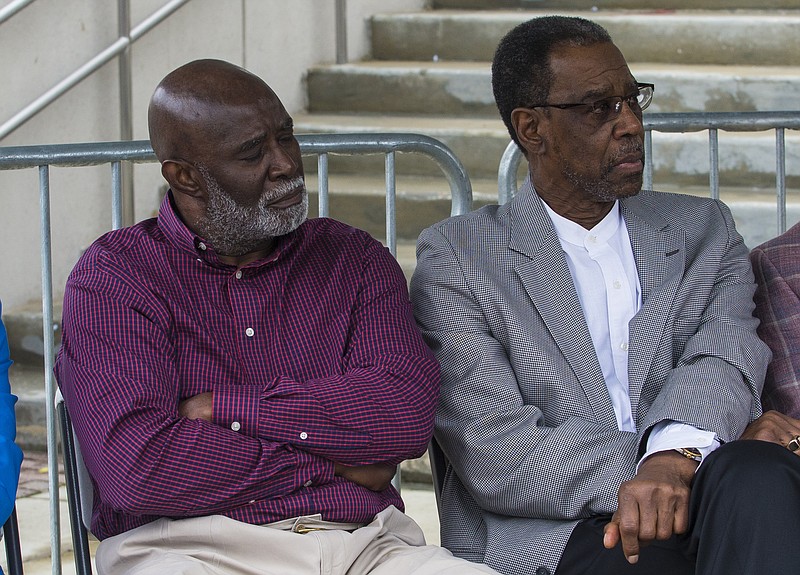

AP photo by Vasha Hunt / Former Alabama football players Wilbur Jackson, left and John Mitchell pull the drapes off a plaque commemorating their pioneer roles for the program during a ceremony outside Bryant-Denny Stadium before Saturday's A-Day spring game in Tuscaloosa. Also at left are university president Stuart R. Bell and football coach Nick Saban, while at right is Christine Taylor, vice president and associate provost for diversity, equity and inclusion.

AP photo by Vasha Hunt / Former Alabama football players Wilbur Jackson, left and John Mitchell pull the drapes off a plaque commemorating their pioneer roles for the program during a ceremony outside Bryant-Denny Stadium before Saturday's A-Day spring game in Tuscaloosa. Also at left are university president Stuart R. Bell and football coach Nick Saban, while at right is Christine Taylor, vice president and associate provost for diversity, equity and inclusion.Jackson and Mitchell each said Bryant told them if they ever had a problem to come see him first. Both said they never had to make a trip to the legendary coach's office for that reason.

"A lot of people don't understand the situation back then," Mitchell said in a phone interview with AP earlier in the week. "Coach Bryant handled the situation as well as any coach could handle it. And I've said this before: If it had been anybody but Coach Bryant, the situation probably could have been different.

"He didn't treat me any different, or Wilbur, than any other players on the team."

Mitchell coached Alabama's defensive line as part of Bryant's staff from 1973-76 and still uses lessons learned from that time - he even saved the notes from those staff meetings.

Back then, Mitchell roomed with white teammate Bobby Stanford, who remains a close friend and was a member of his wedding party.

In a recent phone interview, Stanford recounted how Mitchell came to Bryant's attention in the first place. Southern California coach John McKay had mentioned to Bryant that the Mobile native was planning to come play for him in Los Angeles. Bryant excused himself and called back to Tuscaloosa, ordering an assistant to track Mitchell down.

"Worst mistake John McKay ever made was telling Coach Bryant about him," Stanford said. "Coach Bryant had been trying to sign Black ballplayers for years, and the power structure in the state of Alabama wouldn't have it. Even as strong as Coach Bryant was, it wasn't easy. He tried."

And ultimately, he succeeded. So did Mitchell and Jackson.