One warm summer's night in the 1990s, Anne Exum found herself in a darkened corridor of Historic Engel Stadium as she dressed up a hot dog during a Chattanooga Lookouts game.

Behind her at that moment stood a man talking to his daughter on a pay phone.

"Sweetheart," she heard him say, "I'm so sorry I'm missing your birthday. I just wanted you to know Daddy loves you and misses you."

Finding this gesture both sweet and touching, the mother of two turned around to discover the man she'd been listening to was none other than Bill Buckner, the former Boston Red Sox player who was a roving hitting instructor with the Chicago White Sox by then.

"I've never forgotten that," Exum said Tuesday morning, the day after Buckner sadly lost his battle with Lewy body dementia at the tender age of 69. "I've always been a Red Sox fan, and I always liked Buckner, but I looked at him a little differently after that, as someone who was a really good husband and father."

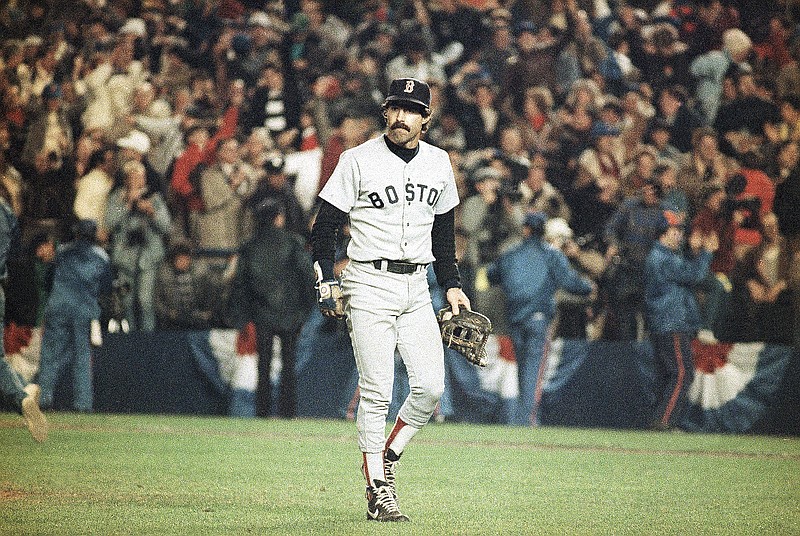

For too many folks - hundreds of thousands of Red Sox fans, truth be known - it took far too long to look at Buckner as anything but a goat following his error in the bottom of the 10th inning of the sixth game of the 1986 World Series against the New York Mets.

Never mind that the game was tied at 5 at that moment after the Sox had entered the bottom of the inning with a 5-3 lead. Or that Boston led Game 7 by a 3-0 score entering the sixth inning before losing 8-5. Or that Buckner was playing on legs so gimpy he'd had to take cortisone shots nine times that season just to stay on the field because Boston manager John McNamara didn't trust the younger, more able-bodied Dave Stapleton. As McNamara would confide to a reporter years later, "Dave Stapleton's nickname was 'Shaky.'"

But it was Buckner who allowed Mookie Wilson's slow, bouncing grounder to roll between his legs at first, which allowed the Mets' Ray Knight to score the winning run, forcing the pivotal Game 7 at New York's Shea Stadium two nights later.

And that single error in an otherwise sparkling career haunted Buckner for much of the rest of his life, if only because no one much seemed interested in allowing him to forget it.

"He handled it amazingly well, but it killed him (emotionally)," longtime Buckner friend and fellow MLB player Bobby Valentine told the New York Times. "There were probably 50 interviews where he could have blamed McNamara, or said something about (pitcher Bob) Stanley throwing the wild pitch, or anything else about Game 6. He never said any of that."

The worst part was, if Buckner didn't quite have a Hall of Fame career, he was within the area code with career numbers that included a .289 batting average, 2,715 hits, 498 doubles, 174 home runs and 1,208 RBIs in 2,517 major league games.

Moreover, he won the 1980 National League batting title (.324), was a 1981 All-Star and played for parts of 22 seasons, retiring at the age of 40 after breaking into the majors at 19.

Tweeted Mets great Keith Hernandez at Buckner's passing: "He was a terrific hitter as well as a human being. Tears."

How terrific a hitter? Noted baseball writer Jayson Stark observed in a tweet that only five players from 1972 through 1982 with a minimum of 5,500 at-bats batted .300. They were Rod Carew (.340), Al Oliver (.312), Pete Rose (.308), Steve Garvey (.304) and Buckner (.300).

Somewhat surprisingly, Carew is the only one of the five to reach the Hall of Fame.

Yet even more impressive when it comes to Buckner the hitter, he never struck out three times in a single game. On Sunday, the day before he died, 16 major leaguers struck out three times. In fact, his 4.5% career strikeout rate is the fourth-lowest of the post-1960 expansion era.

Yet that wasn't what made Buckner most special. It was that kinder, gentler, sweeter side. Or as Garvey included in a Monday tweet: "He was a dear friend, a strong Christian and wonderful husband and father."

That's no doubt what Jody - his wife of 39 years - his daughters Brittany and Christen and son Bobby saw in him every day. It's what Exum saw in him while overhearing a single phone conversation at Engel Stadium.

He surely never heard enough kind comments from others, though the Red Sox Nation did, perhaps out of supreme guilt, give him a two-minute standing ovation when he returned to Fenway Park in 2008 to throw out the ceremonial first pitch before a game. But as time passed he didn't seem to care.

Or as Buckner said in a 2005 interview: "A lot of people have come up to me and said, 'You really helped me in my life. I looked at what you had to go through, and how you handled it, and my life is better because of that.' When I look back at my job, baseball and my life, I maxed out. I did physically everything I could do. What more could you ask of yourself?"

For those who asked or expected more of him, that error was on them, not him.

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com.