The first day of school in 1965 was not going as planned for Levi and Terry Scott. Attending previously all-white Bradley Central High School for the first time, the Scott brothers, who are Black, were experiencing more than a wee bit of racial tension.

"We were scared," Levi said as he recalled the transition from Cleveland's College Hill, an all-Black high school. "We'd never previously been around a bunch of white people before."

Soon enough, he found himself surrounded by several Bradley students not too happy to see him.

"They started kicking at me, pushing me, calling me the N-word," Levi said. "I was worried about what would happen next."

What happened next was the arrival of Mike Fitzgerald and a couple of his fairly large fellow football players.

"I told them Levi was my friend and he was going to help our basketball team," Fitzgerald remembered. "They left him alone after that."

Some of that acceptance was no doubt due to basketball.

"When they found out we could dunk," Levi said, "everybody starting being nice to us."

Said Fitzgerald nearly 55 years later: "That's what sports does. It brings people together."

We have rarely needed to be brought together in this country more than now. When we combine the coronavirus pandemic, racial unrest and a potential economic calamity, our patience and emotions are being tested like never before. And much like the mid-1960s, our young people are right in the middle of it. Should they go to school? Should they learn online? A mix of the two? Should we play sports at all? In some abbreviated form? With fans in the stands? No fans?

Just studying and attempting to understand all those options is enough to send the calmest and most balanced of souls into therapy.

But in 1965, Fitzgerald was anything but your typical white teenager befriending a handful of Black students attending his high school for the very first time. He was the son of noted professional baseball scout and minor league manager Lou Fitzgerald, who managed the San Antonio Bullets - a Class AA farm club of the Houston Colt .45s (later the Astros) - to consecutive Texas League pennants in 1963 and 1964.

"That team had (future Hall of Famer) Joe Morgan and (longtime Astros star) Jim Wynn, who were both Black," Fitzgerald said. "I was often a bat boy for my dad's teams in the summer. I saw how he handled racial situations. If we stopped at a hotel or restaurant that didn't serve Blacks, my dad would just say, 'Well, we'll just have to find someplace else,' and we'd move on. I learned a lot about how to treat people from my father."

So after watching Levi and Terry Scott and Charles "Bozo" Queener walk a good distance from their Cleveland homes to Bradley Central for a couple of days, Fitzgerald agreed to take them to school and bring them home for a fee.

"Twenty-five cents a week," said Queener, who only got to play his senior season at Bradley because of a TSSAA transfer issue.

Added Levi, whose younger sister Gloria was later part of one of Pat Summitt's national title teams at Tennessee and whose younger brother Alvin became a longtime star with the NBA's Phoenix Suns: "Every time we see each other, Mike says I still owe him 75 cents."

But they also had other things to say about Fitzgerald.

Levi: "That's my brother, right there. He's my closest friend."

Queener: "If it hadn't been for Mike, I might not have made it. He's meant the world to me."

To better explain the Bradley County of the mid-1960s, Fitzgerald remembers taking a short walk from his Dalton Pike home to view Ku Klux Klan rallies from a distance in South Cleveland.

"I don't ever remember them burning anything," he said, "but I remember the robes they'd wear and the pointy hats. They'd rant and rage. They scared the heck out of me."

Levi and Queener recalled similar horrors. Of today's racial unrest, Queener said simply, "I think what we went through was a little tougher."

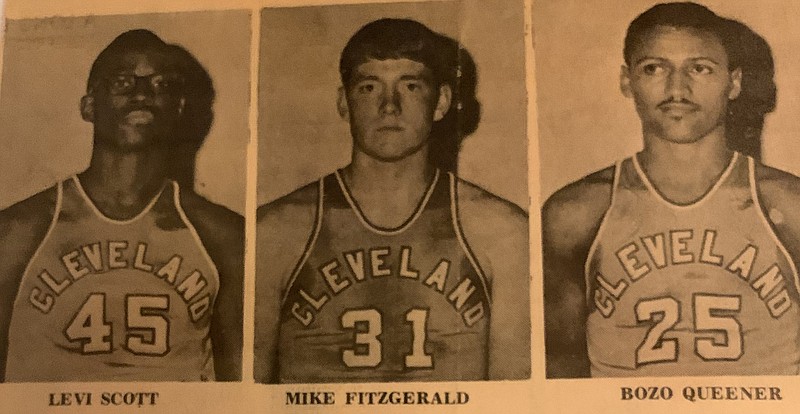

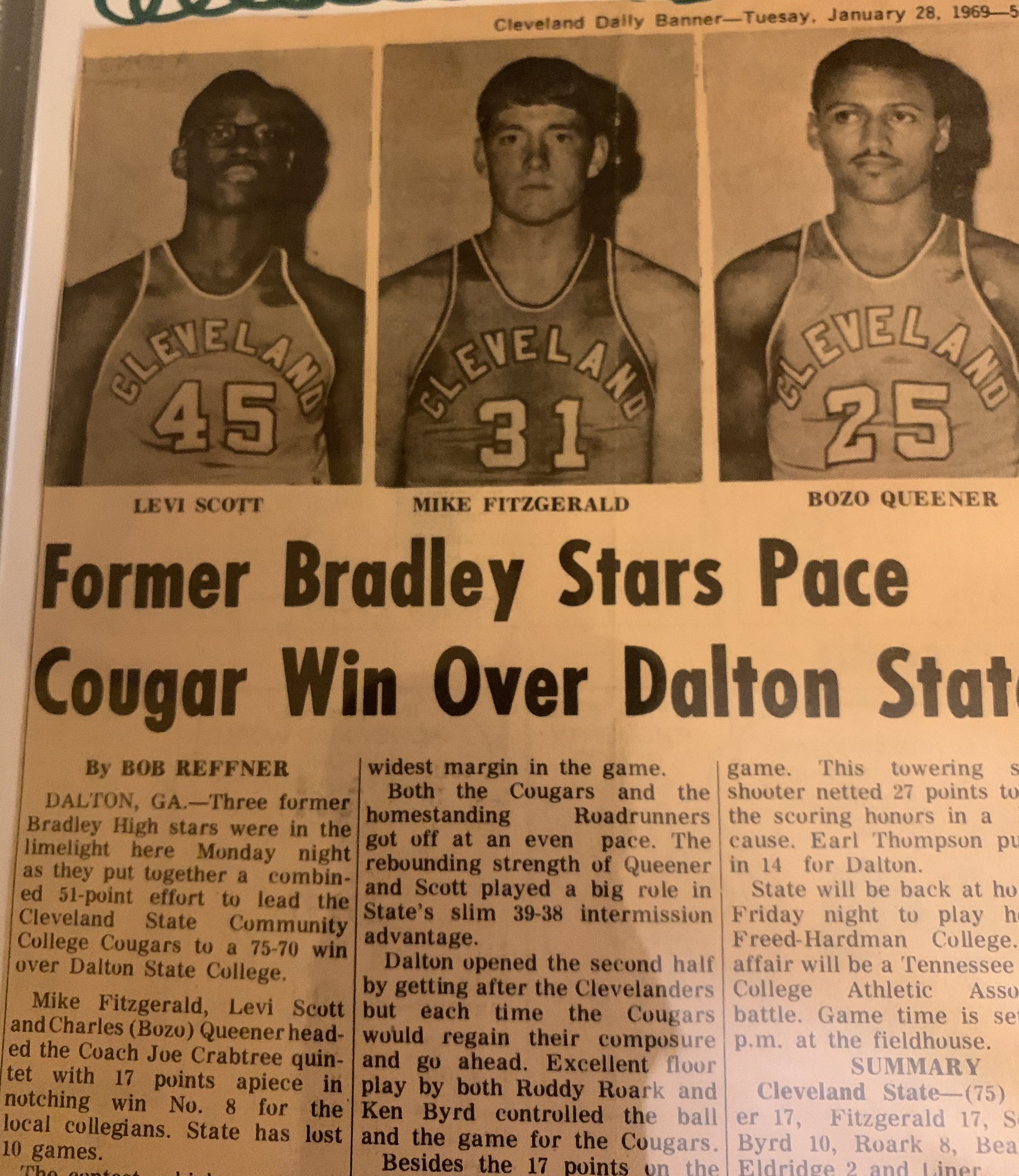

But there were also good times at Bradley Central and later at Cleveland State, where Levi and Queener would eventually be inducted into the Cougars' athletics hall of fame as basketball players, with Fitzgerald going in for baseball. Terry Scott is in Middle Tennessee State's athletics hall of fame.

"We'd go to Mike's house sometimes," Queener said. "His mom would fix us something to eat. Not many people would do that back then."

There were also some entertaining hoops memories due to Fitzgerald's alter-ego "Hotch," who convinced Bears basketball coach Bill Walker that he could jinx opposing free throw shooters by sitting on the bench shaking his hands while the opponent stood at the line.

"I swear it worked 90% of the time," Fitzgerald said. "I got so good at it that Coach Walker would have me sit next to him on the bench late in the game when I did it."

This led to a bit of chicanery late in a game against Oak Ridge when Levi was fouled and appeared to hurt himself when he wound up under the scorer's table.

"I was a terrible free throw shooter," Levi said. "Coach told me to stay down. Then he sent Mike into the game to shoot my free throws. He hit them both and we won by one point."

Alas, that 1967 team's playoff run ended in a sub-state loss to Howard when the Hustlin' Tigers' Randall High nailed a jumper at the buzzer.

Yet for Levi, Queener and Fitzgerald, who all still live in the area, the friendship that began in 1965 has strengthened over the past 55 years as they all now approach the north side of 70 years old.

"We don't see each other enough," Fitzgerald said, "but we'll always be great friends."

Added Queener: "It's amazing to me that Mike always knows if I've been sick or something. He's always checking up on us."

So how was it that Fitzgerald understood so early in life that Black lives matter?

"I guess I was just raised right," he said.

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @TFPWeeds.