Sometime in the early 2000s, a few years after the Atlanta Braves moved to Turner Field, I got on an elevator one Sunday afternoon to make my way to the press box.

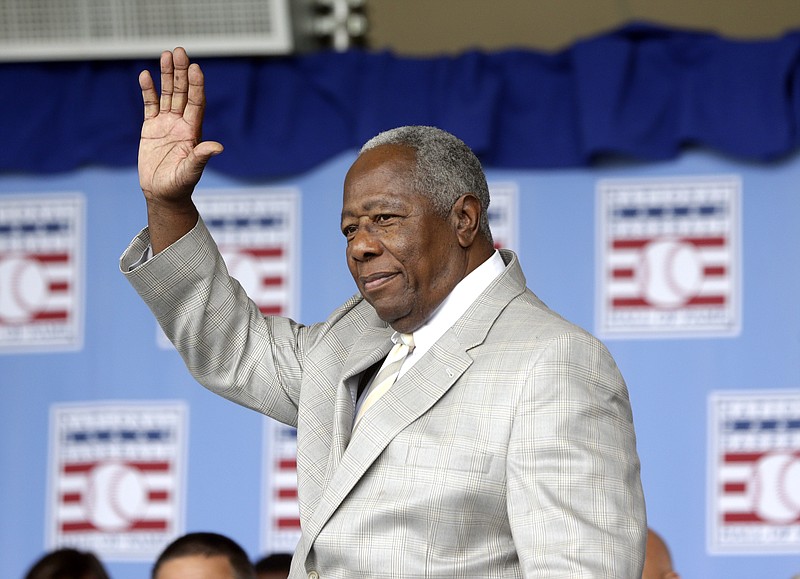

Already inside it were Hank Aaron and four or five other men, all of us thrilled to be in the company of one of the three or four best hitters in the history of professional baseball.

As we exited the elevator a minute or two later, one young man turned to Hammerin' Hank and said, "Would you mind if I asked for your autograph, Mr. Aaron?"

Said Aaron, a warm and easy grin spreading across his face: "I wouldn't mind at all. It's nice to be remembered."

If there's ever been a more decent, dignified and gracious sports superstar than Aaron, I'm unaware of them.

Even in the final weeks before his death Friday at the age of 86, the man who will go down as the leading home run hitter of all time without the aid of chemicals (Barry Bonds, tainted by performance enhancers, has seven more than Aaron's career 755), was still providing a positive example for others to follow.

Just this month he received one of the earliest COVID-19 vaccines, an effort to assure Black Americans the vaccine was safe.

"I don't have any qualms about it at all, you know," he told the media. "It's just a small thing that can help zillions of people in this country."

AP photo by John Bazemore / Les Motes and his 2-year-old daughter Mahalia leave flowers Friday in Atlanta near the spot where Hank Aaron's record-setting 715th home run landed on April 8, 1974, as the Braves hosted the Los Angeles Dodgers at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Aaron's death Friday at age 86 drew an outpouring of reactions from around baseball and beyond.

AP photo by John Bazemore / Les Motes and his 2-year-old daughter Mahalia leave flowers Friday in Atlanta near the spot where Hank Aaron's record-setting 715th home run landed on April 8, 1974, as the Braves hosted the Los Angeles Dodgers at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Aaron's death Friday at age 86 drew an outpouring of reactions from around baseball and beyond.How Aaron carried himself throughout most of a career too often marred by others' racism and bigotry was anything but a small thing, especially the restraint he showed as he was about to overtake Babe Ruth's major league mark of 714 career home runs, once considered untouchable.

A native of Mobile, Alabama, Aaron had grown up in poverty and prejudice, occasionally recalling how his mother would hide him and his seven siblings under their beds whenever the Ku Klux Klan would march down their street.

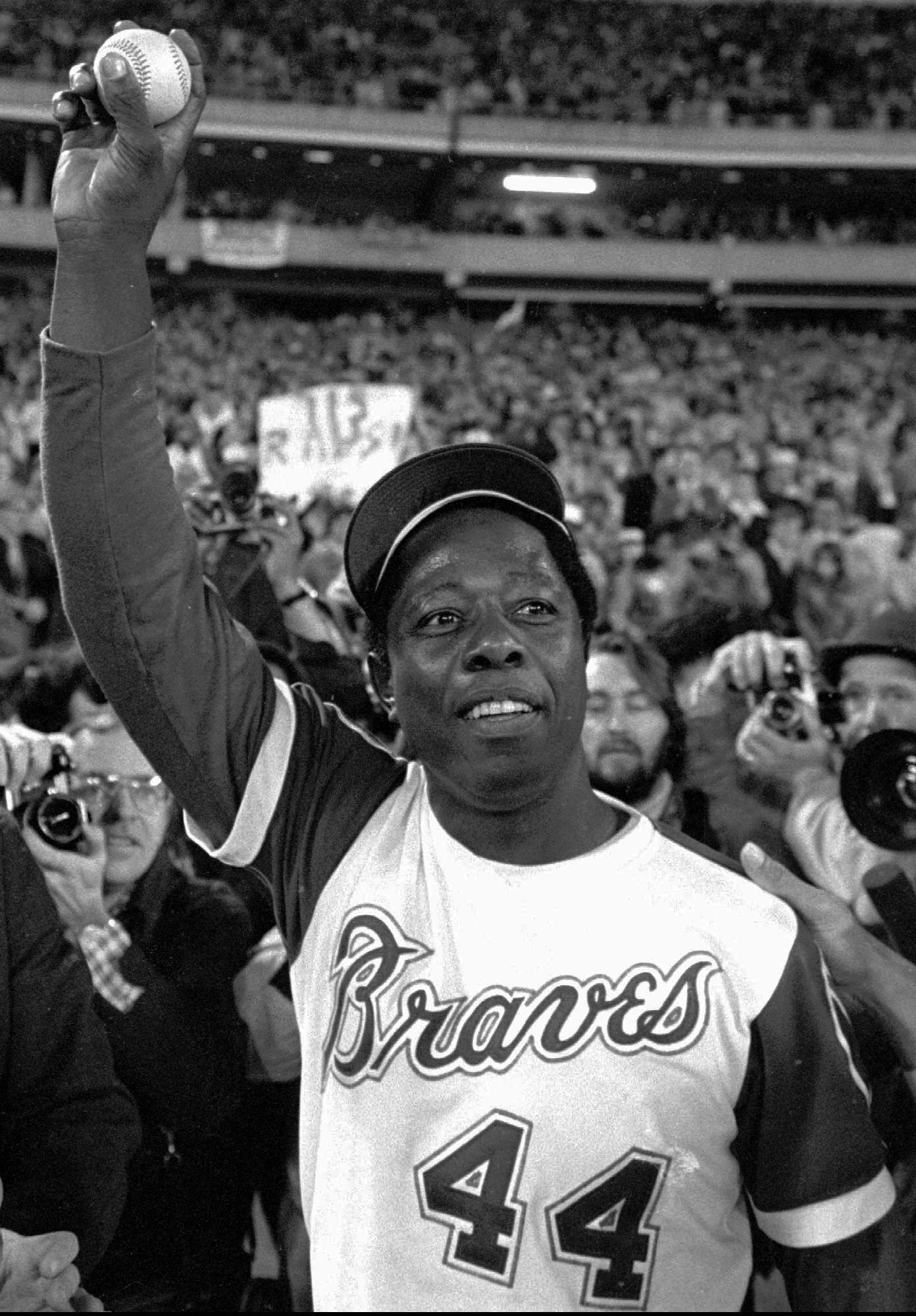

Yet despite coming of age in such a troubling time in American history, he rarely allowed his emotions to boil over in public, even when he was receiving 3,000 pieces of hate mail a day in the weeks before he would break Ruth's home run mark on April 8, 1974, swatting No. 715 off the Los Angeles Dodgers' Al Downing that night inside Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

According to the Associated Press, he did admit a year before the record was broken: "If I was white, all America would be proud of me. But I am Black."

Much later, he also lamented: "It was supposed to be the greatest triumph of my life, but I was never allowed to enjoy it. I couldn't wait for it to be over."

He mostly kept those frustrations to himself, though, realizing that would only make the bad guys behave even worse, maybe even tormenting his family.

On the night he broke the record, two white teenagers somehow made their way onto the field, catching up to him and running a couple of bases alongside Aaron, patting him on the back as he ran. According to ESPN, what most never knew was that as the star slugger rounded those bases, his bodyguard, Calvin Wardlaw, was in the stands holding a gun, attempting to determine whether those two young fans meant Aaron harm and whether he should shoot them to protect the player.

Thankfully, Wardlaw never fired his weapon, the two teenagers ran back toward the stands and the legendary Dodgers radio announcer Vin Scully, after pausing for 30 seconds to let his audience hear the roar, delivered the following gem: "What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. It is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron."

But if you think that moment was a turning point in how the most famous Black athlete in Atlanta sports history was viewed and respected, that Aaron would thereafter be seen by his own employer, the Braves, as the national treasure he was, you'd be wrong.

The Braves traded him to the Milwaukee Brewers at the close of that season when he balked at a front office position that would have paid him roughly 25% of the salary he was making as a player.

"Titles?" he said at the time, according to the AP. "Can you spend titles at the grocery store? Executive vice president, assistant to the executive vice president, what does it mean if it doesn't pay good money?"

Yet there he also so often stood in his latter years, having finally joined the front office, a Braves legend seemingly happy to be a Braves legend whenever they asked him back to recognize his accomplishments. Time heals most wounds if you allow it.

And no Brave has ever accomplished more than Aaron, who was a first-ballot selection for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom - the nation's highest civilian honor - from George W. Bush in 2002 and still holds the major league records for RBIs (2,297), extra-base hits (1,477) and total bases (6,856).

Amazingly, it almost didn't happen. At least not as an Atlanta Brave.

The excellent ESPN writer Howard Bryant told that network's Stephen A. Smith on Friday of Aaron's original reluctance to return to his native South when the Milwaukee Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966. A meeting was set up with civil rights giants Ralph David Abernathy, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Andrew Young.

Said Bryant: "They told him 'You're as important to this (civil rights) movement and Black people as we are. We need you to come here."

Because had he not, and had he not done so with such decency and dignity and grace, what a marvelous moment for the country and the world - a Black man getting a standing ovation in the Deep South, escorted around the bases by a couple of white teenagers - we would have missed.

And, oh, how much these days we need zillions of us in this country to rediscover that color-blind joy in every facet of our lives.

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @TFPWeeds.