"I'm telling you, if I don't get out of this house, I'm going to go stir crazy!"

My buddy sounded a little desperate, to say the least.

"I've been staring at these walls for two weeks, and I can't watch any more 'Gunsmoke' episodes. I'm even tired of Miss Kitty!"

Now I knew he was serious, and I would have to do something. Still, I had to throw in a warning.

"Ah, uh, bud, you know we are supposed to be social distancing," I replied, letting my words trail off to see what his reaction would be. I could hear his blood pressure go up over the phone.

"I haven't seen anyone except the guy that delivers my propane, and that was at least two weeks ago," he snapped. "What about you?"

I admitted to seeing a few more people than that, but really it had just been me and three crazy dogs for a few weeks.

"Well then, if we stay at least six feet apart, we should be OK. I wasn't planning on hugging your neck anyway," he said, stating the obvious. "I'll meet you at High Rocks at 0600, and we'll go for a walk.

I wasn't ready when he slammed down the phone. I assumed we were finished talking.

I assembled a few things in a vest, as I knew we could be in the boonies for several hours. To this guy, "a walk" could cover a lot of ground.

I was only able to drag myself out of a warm bed in the morning for fear of being chastised by you know who. I knew he would beat me to the rendezvous point, and sure enough the lights of my truck caught him standing there as I pulled up; being on time was late for him. I grabbed what I could, took a last gulp of coffee and followed where he had disappeared into the dark.

The first order of business would be to get to a listening post. I knew he would head for the high knob on the ridge that lay before us. From this point we could hear any turkey that decided to gobble this morning. This day seemed like it would be beautiful. The stars were shining intensely, a low moon was hanging and a glow was starting in the east. If no turkey gobbled today, it would be his fault.

I was out of breath when I pulled up on the knob; he was already there, of course, and stood apart from me as I tried to catch my breath. We stood in silence for several minutes as another day began in the world. The cardinals and other tweety birds first, then a few distant crows. We waited for the gobble that didn't come.

Just as we started to leave and took several steps, he stopped and looked at me with a face that said "Did you hear that?" Yes, I did, and another distant gobble came from the ridge to our west, then another. Well, one mission had been accomplished. This was just a scouting trip, but it was nice to hear a couple turkeys with hunting season a few weeks away.

Now I knew we would take a detour and go to phase two, and that would be ramps.

Most of you in the Appalachians know what ramps are, but in case you don't, they are wild leeks. While they may resemble scallions, they are not onions and have their own taste and fragrance. Much like bluegrass music, you probably either love ramps or hate them. Many people love them, and they can be eaten raw (if you really want to social distance) and there is a tradition of ramp festivals in West Virginia and several other states where hundreds of people will gather to partake of ramps, fried potatoes, ham, brown beans and cornbread.

Ramps are about the first thing green that comes out of the ground in the hills each year, and the early mountaineers thought of them as a spring tonic, as many still do today.

We both dug a Wally World bag of the aromatic ramps and started the long trek downhill to the creek. I didn't mind this part of the hike, but I knew every inch of elevation we lost would have to be regained when we came back. I told myself if we found the subject of our next quest, it would be worth it.

The brook trout is the only trout native to the eastern United States, and to make things even more complicated, the biologists tell us he is not really a trout. The scientists who worry about such things tell us this fish is in fact a member of the char family. Salmon, trout and char in my opinion are so closely related that you couldn't tell the difference between them at a family reunion, but biologists may disagree with me.

Brook trout live only in clear, cold mountain streams, usually in wild places. They are beautiful little trout, and unfortunately for them, they are absolutely delicious. Trout raised in a hatchery cannot hold a candle to a wild brook trout.

Once on the creek, we cut saplings for makeshift fishing poles. The creek was beautiful, and we had caught trout here before, but today was not our day to find the brook trout. Knowing it was a long trek back to the truck, we sat on the creek bank for a while and enjoyed the sunshine. Glancing over at my buddy, I hoped he would be good now to go back to Marshall Dillon and Miss Kitty.

I figured two out of three wasn't bad. We heard a turkey and dug some ramps; maybe we would get the brook trout next time.

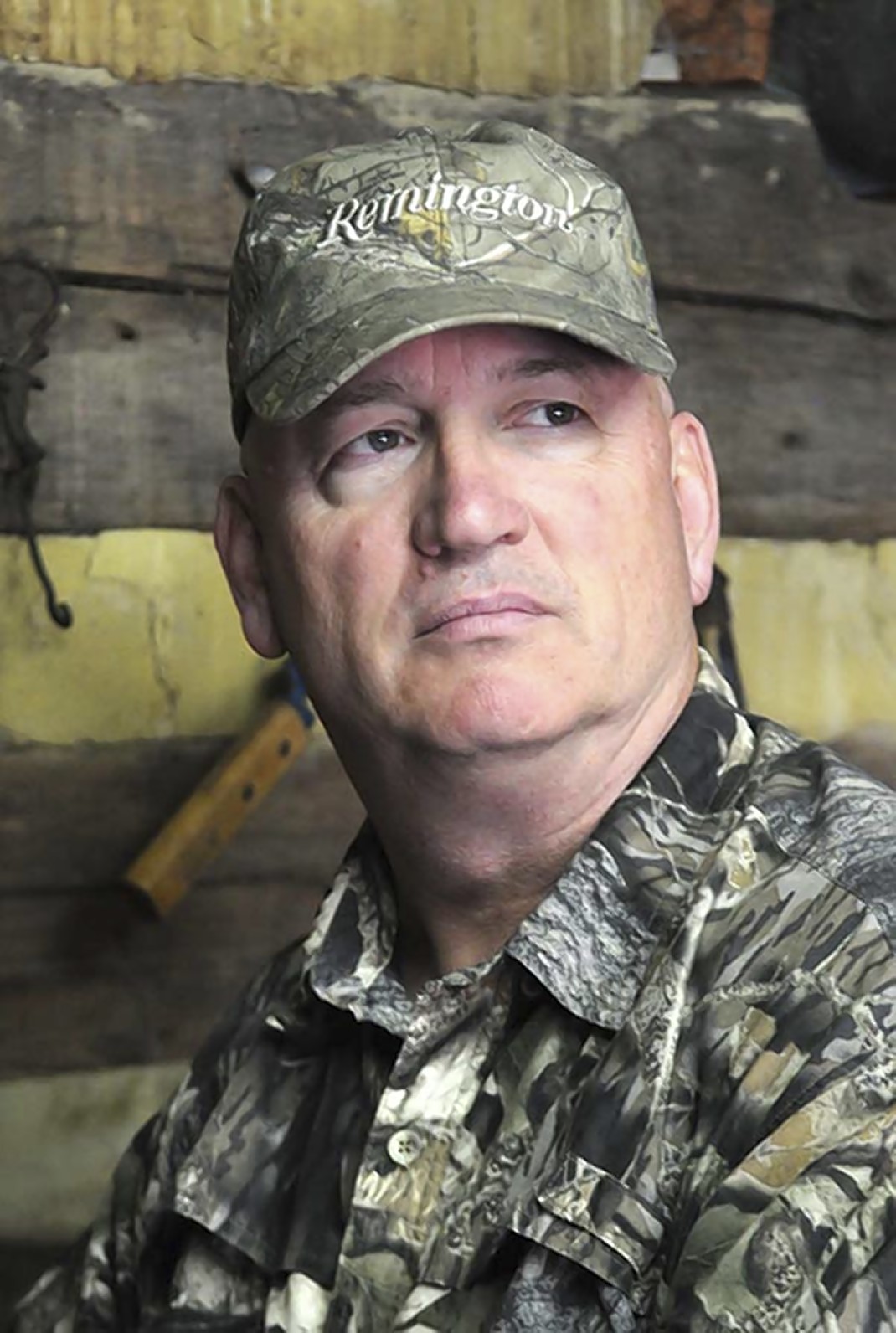

"The Trail Less Traveled" is written by Larry Case, who lives in Fayette County, W.Va. You can write to him at larryocase3@gmail.com.