WHO IS BURIED THERE?Five of the most notable:Samuel Frazier: The man for whom Frazier Avenue is named was born in Rhea County and became a first lieutenant in the 19th Tennessee infantry. He fought at Shiloh and Vicksburg before he was wounded at Chickamauga and taken as a prisoner of war to Chattanooga. Following his recovery, he was sent north to a prison camp for the remainder of the war. He settled in Rhea County after the war and practiced law before abandoning the profession in 1882 and moving to Chattanooga where he started "Hill City" just north of downtown. He donated $10,000 for the construction of the Walnut Street Bridge, which was built in 1890. Frazier died in 1921.Martin Fry: Enlisted in the Tennessee infantry at age 16 and saw action in many of the war's major battles in the western theater. While returning to his middle Tennessee home after the war in 1865, he was arrested in Pulaski, Tenn., on charges that he killed a man and burned a bridge. Fry was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson, a Tennessean, and returned to live in the rural countryside of Alton Park. He died in 1926.Ben Goulding: A notable Chattanooga philanthropist who began a weather bureau in the city among numerous other civic actions following his participation in the war. Goulding died in 1934.Shadrick Searcy: An African-American who received a Confederate pension and opted to be buried in the Chattanooga Confederate Cemetery after the two brothers he served with died in action during the war. Following their death, Searcy remained in the Confederate service. He moved to Chattanooga in 1903 to work for the railroad and died in 1935.Edward Wentworth: A sergeant in the Union's 19th Michigan Infantry, Wentworth was captured at Thompson's Station in Williamson County by Confederates and transported to Chattanooga where he died.

The American Civil War has been over for nearly 150 years, but the struggle to preserve the history of those who fought continues.

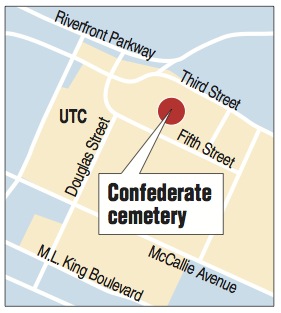

And Herb DeLoach is doing everything he can to win the battle at the Chattanooga Confederate Cemetery on Fifth Street.

Things look better at the historic resting place of hundreds of Confederate veterans than they did 20 years ago, but without federal funding, corporate backing or much city help, the cemetery relies on a local camp of the Sons of Confederate Veterans for maintenance and upkeep.

At the moment, that means DeLoach, the great-grandson of Alabama infantryman Robert DeLoach, hops on his 46-year-old lawnmower every so often and spends the day keeping the cemetery from becoming overgrown like it did in the early 1990s.

"It takes between six and eight hours to do the whole job," said DeLoach, a 74-year-old retired aircraft maintenance supervisor. "But I don't mind. These guys, it's almost like they know you're here. That sounds strange, I know, but it's a labor of love for us and our camp."

Though the cemetery is the city's property, responsibility for the plot is claimed by N.B. Forrest Camp 3 in accordance with a national emphasis by the Sons of Confederate Veterans on Confederate burial places.

All of the needed tune-ups at the Chattanooga Confederate Cemetery would require $100,000, the local chapter says. But with the primary revenue for the cemetery coming from DVD sales and other fundraisers at area Civil War shows, the 88-member chapter is taking things one project at a time.

Last month the City Council approved a resolution accepting $5,790 from the camp for repairs at the cemetery's pavilion.

"It [the cemetery] means a great deal to a number of our local citizens," City Council Chairman Yusuf Hakeem said. "We've partnered with so many other entities and organizations. We didn't see it as an issue as far as partnering with that group for this. The fact that it doesn't cost the city anything, it makes it that much more attractive."

DeLoach, the adjutant of the chapter, has seen how the old city cemetery next to the Confederate portion was poorly maintained in the past. He wants a different fate for the plot that holds both soldiers who died during the war and some who chose to be buried there long after it.

Nationally, things are no different. Gene Hogan, chief of heritage operations for the Sons of Confederate Veterans, said camps work with municipally owned cemeteries across the South to ensure that Confederate cemeteries are not overlooked.

"I would say just the overall maintenance, adornment, protection and preservation of a Confederate burial site, there's really just no higher priority we have than that," he said. "That is so critical to who we are and what we're called to do as an organization."

Many of the plaques, monuments and other bits of commemoration around the cemetery, like the wrought-iron battle flag gate along Fifth Street, are more than 100 years old. Confederate veterans purchased the northern part of the cemetery in 1867 from George Gardenhire and acquired the rest of it for one dollar in 1901 from the Gardenhire family under the provision that it would also be used as a Confederate cemetery.

When the last associate member of the local Confederate Veterans camp died in the 1950s, it left the city as the sole trustee of the cemetery. In 1994 Chattanooga Mayor Gene Roberts authorized cooperation with the Sons of Confederate Veterans to help restore the cemetery that had become overgrown and a rededication ensued in 1995.

"We've tried to maintain it and take better care of it since then," DeLoach said. "But it is a real fight."

The future of the cemetery will soon lie in the hands of a younger generation, a generation that DeLoach worries about. Since the victors get to tell how the war was won, he worries that future Confederate descendants may grow up without a true understanding of the motives that drove their ancestors to fight for independence.

But for now, he is happy to continue devoting time to maintaining the cemetery.

"We're bound to do this," he said. "As long as I can function and get on that 46-year-old tractor [I'll do it]. As long as I can get on that thing and crank it up."

Contact staff writer David Cobb @dcobb@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6731.