HOW IT WORKSIn 2014, people applying for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits must go through this process:• All individuals must take a screening test, a written examination with questions geared to detect when a person might be using drugs.• If the person's answers raise a concern, he or she must pass a urine drug test for five types of illegal narcotics.• Applicants who fail the urine test must enter a treatment program to retain benefits. Without treatment, these individuals would be ineligible for benefits for six months.• After treatment, they must pass another urine test to maintain their benefits. Those who fail this test would lose benefits for six months, or up to a year in a repeat offense.

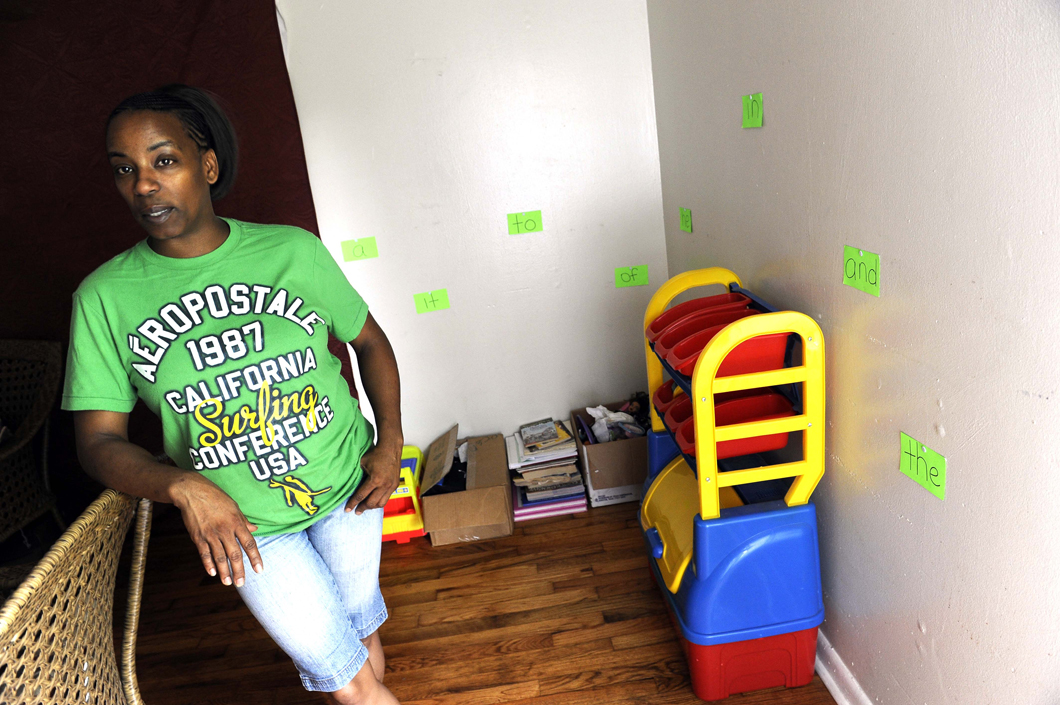

Yolanda Powers is willing to take a drug test to qualify for welfare.

But she doesn't think people struggling to get back on their feet should have to pay for it.

Like many of the thousands of Tennesseans receiving benefits under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, Powers says new legislation passed by the state legislature this month doesn't bother her.

The legislation, which Gov. Bill Haslam has said he will sign, is similar to a number of controversial and constitutionally suspect laws in other states. But Powers said allowing the state to test for drugs provides a way to make sure state funds are used appropriately.

"You have to realize that it's taxpayers' money," she said, "and it's a lot of people not doing the right thing."

While Powers said state officials "weren't going to have a problem" with the results of her test, she doesn't expect to stay on welfare long enough to see the future law and its policies go into effect. She's in too much of a hurry to improve her situation.

After losing her job at a local restaurant, the mother of five and soon-to-be grandmother plans to open a small child care center at her home near Tennessee State University. A corner of her home is already lined with donated books, toys and other things to help care for the four children she expects to have in the day care.

While she supports the idea of Tennesseans being tested, Powers didn't think recipients should have to pay for the test. That was a proposal floated during the legislative debate but ultimately not included in the law.

"Now that might not be a good idea," she said. "You have to be able to pay your bills and have to put food on the table and sustain a home."

It's not certain who will foot the bill for the testing program, because lawmakers left the policy unclear.

The legislation's latest fiscal note said TANF beneficiaries would cover the costs of the drug tests, estimated at one time to be around $30 apiece. But its Senate sponsor, Sen. Stacey Campfield, R-Knoxville, said after the bill passed that the Department of Human Services would try to help people pay for screenings and possibly the drug tests. A DHS official, Valisa Thompson, said development of the program will not start until July, so nothing specific about it has been determined -- including who will bear what costs.

"The department will develop the plan with a goal of minimizing financial impact for all parties," Thompson said in a statement.

But even as officials develop an implementation plan for the program -- estimated to cost more than $200,000 on average in each of the next three years -- they may have to confront constitutional questions.

Laws passed in Michigan and Florida that allowed tests without any prior suspicion were either deemed unconstitutional or challenged in court after federal judges said the tests lacked the proper cause for conducting a search, as required by the U.S. Constitution's Fourth Amendment.

Previous versions of the Tennessee legislation faced similar questions from state Attorney General Robert E. Cooper Jr., who issued two opinions questioning the bill's legality. The legislation was updated to make sure the drug tests would be suspicion-based, mainly by adding the screening process. That adjustment addressed the attorney general's written concerns, said Leigh Ann Apple Jones, Cooper's chief of staff, in an email.

Cooper has yet to weigh in formally on the current bill, but others say the new law might not withstand a constitutional challenge.

"I don't think it comes close. It's undefined and unspecified," said Ed Rubin, a professor of law and political science at Vanderbilt University. "It just allows for general surveillance. It doesn't provide any probable cause, which is required by the Fourth Amendment."

Rubin said that while the Fourth Amendment does allow people seeking certain jobs, such as airplane pilots and machinery operators, to undergo mandatory drug tests, cases like these occur when public safety is at stake.

"That rationale is completely lacking here," he said. "There is no plausible public safety argument from the general Fourth Amendment."

The legislation also has drawn criticism from the Tennessee chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which sent a letter to the governor calling the bill into question and urging Haslam to veto it.

The organization has not yet decided whether to sue the state, said Hedy Weinberg, executive director for the ACLU's Tennessee chapter. State chapters of the ACLU sued over similar legislation in Florida and Michigan. The state already expects to spend more than $100,000 in legal costs, according to the bill's fiscal note.

Weinberg said the legislation lacks clear guidelines and needs clarification, including its implementation policy and treatment referral process, but still might not pass the legal test.

"The bottom line is that it targets a certain socioeconomic group of people without suspicion or probable cause," she said.