Did you know that ...

Due to their poor eyesight and murky aquatic environment, electric eels have developed a keen sense of hearing that is aided by a modified vertebrae between their inner ear and swim bladder that detects and interprets pressure changes in the water. Because of their eyesight, they navigate and sense prey using discharges as a kind of radar or echolocation. Electric eels aren't actually eels but a type of knifefish. Unlike true eels, they lack pelvic and dorsal fins and live exclusively in freshwater. Scientists classify them similarly to carp or catfish. When electric eels reproduce, the males build a nest using their saliva and the female deposits batches of eggs into it. A group of electric eels is known as a "swarm." Although there have been reported deaths due to drowning by swimmers who have been stunned by an electric eel, an eel's natural defense mechanism is to remain motionless. A shock from an electric eel lasts about 2 milliseconds, but they can discharge at least 50 times a second. Although they have gills and lack a set of lungs, electric eels are obligatory air breathers and get about 80 percent of their oxygen at the surface through an oral cavity. They will drown if they don't breath once every 10 minutes or so. Eighty percent of their bodies are made up of the three organs that generate electricity. At their most powerful, electric eels have emitted bursts of up to 860 volts, about seven times the current in the typical American electric socket. Source: Tennessee Aquarium, National Geographic

The last few years have proven that social media and animals are natural bedfellows, with thousands -- sometimes millions -- of subscribers keeping tabs on the exploits of surly felines and puffed-up pups. Even Aflac's spokesduck has more than 67,000 followers on Twitter.

So why not an eel?

On Dec. 15, the Tennessee Aquarium's newly installed Amazonian electric eel, Miguel Wattson -- get it, Watts-on? -- registered an account on Twitter that automatically posts messages whenever probes in his tank detect a strong-enough electrical discharge from him.

"Outside the aquarium, there might be people who don't know just how cool electric eels are," says aquarium spokesperson Thom Benson. "This gives us a way to reach a broader audience. I think there's some potential to just have some fun and really capture people's imaginations."

So far, the posts to the account (@EelectricMiguel) have been a mix of environmental conservation messages, scientific facts and groan-inducing fin-slappers, including this quip from Dec. 30:

"If I was an artist, I'd be an eel-ustrator!"

And this one, from Jan. 7: "What do I do in my down time? Brush up on current events!"

Eyeroll-worthy as his sense of humor is, Miguel isn't to blame for the abundance of puns. Behind the scenes, the aquarium staff curates a continually updated database of tweets, with new ones automatically posted with each spike in electric activity.

Miguel moved into the World Gallery of the aquarium's River Journey building just before Thanksgiving and, before he made his social media debut, the staff already had taken steps to ensure his grey, mostly motionless form wasn't overlooked by guests.

Given that an electric eel's emissions are silent and invisible, the aquarium's exhibit design team installed a set of underwater probes connected to an amplifier to translate Miguel's near-continuous electrical discharges into static-y pops that reverberate throughout the gallery.

That auditory showcase, accompanied by a set of LED lights that indicate the strength of each discharge, is enough to attract the attention of those who see Miguel in person, but Benson says the staff also wanted to give him an online presence to help connect with people who hadn't yet or couldn't visit the aquarium.

To cobble together a technological solution that enables a limbless aquatic creature to join the Twitter rank and file, the staff turned to Tennessee Technological University, whose BusinessMedia enter previously had developed the aquarium's smartphone app.

When they were approached, university staff say they were intrigued at the possibilities of the project, which promised to use emerging technologies and require the collaboration of students from several academic disciplines.

"These people from all these different majors are coming together and working things out," says BusinessCenter manager Mack Lunn. "They all speak different languages and all have different personalities and are contributing, and then bang! They've got the job done and done something that hasn't been done before."

Ultimately, the project involved seven students whose majors ranged from environmental studies and web design to education and marketing. The project's lead developer was 20-year-old Evgeny "Zee" Vasilyev, a Russian-born sophomore computer science major.

Early on, Vasilyev says, he decided the solution lay in creating a system that could operate continuously and autonomously, monitoring Miguel's activity and triggering tweets automatically via a connection to the tank's voltmeter.

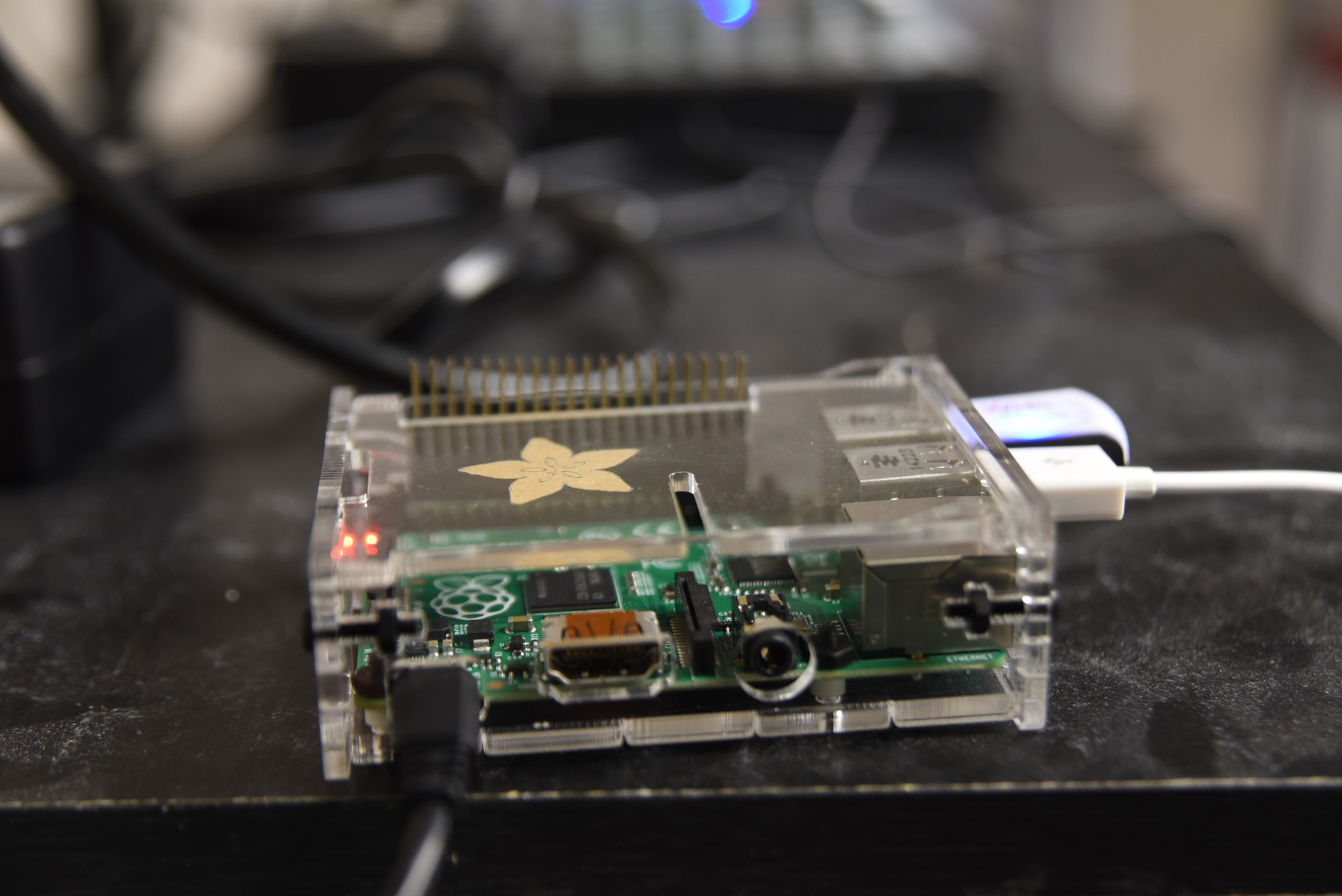

Vasilyev says the obvious solution was to build a device around a Raspberry Pi, an inexpensive, self-contained computing platform that has been used in applications ranging from handheld video game emulators to controlling Christmas light displays.

"I have seen plenty of videos of what that little thing can do, and I knew every pro and con of the Pi," Vasilyev writes in an email. "[It] did exactly what we needed: easy Wi-Fi access, support for multiple programming languages, low power consumption and 24/7 operation."

On a high shelf in a closet behind Miguel's tank, the final product of TTU's efforts is an unassuming plastic box containing a single computer board, a wireless dongle and a connection to the tank's voltmeter.

So far Miguel has tweeted about dozen times and attracted 20 followers. Generally, new posts arrive on Monday, Wednesday and Friday afternoons, when aquarist Brad Thompson deposits chunks of fish and clams into the tank.

During a recent visit, the tank's speakers burst into life when the first silver-scaled morsel lands on Miguel's back, accelerating from a plodding series of pops into a frenetic, machine gun report that sounds like a needle being drawn across a record. Within minutes of this red-line burst, Miguel's account registers a new post: "ZZIINNNGG!"

Although he's the first aquatic resident of the aquarium to join Twitter, Miguel isn't the first to blaze the trail. He's following in the pawprints of Chattanooga Chuck (@ChattNoogaChuck), the aquarium's pudgy groundhog and self-proclaimed "chief seasonal forecaster."

Yes, they follow each other on Twitter.

Contact Casey Phillips at cphillips@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6205. Follow him on Twitter at @PhillipsCTFP.