Read more

Bat cave canoe trips in Nickajack Cave are popular local offeringCavers poised to discover secrets in Missouri cave, Devil's Well

The first time Tim White went caving might have been his last. It was 1984. He was 19 years old and living in Alabama. Back then he didn't know much about caves. To gain experience, he joined the Huntsville Grotto.

A "grotto" is a regional caving club that offers cave training and education and organizes group trips. White's first trip took place in a horizontal cave, which involves crawling and climbing over and under slick, muddy rocks.

He and his group crawled and climbed. Eventually, the narrow passage opened into a small room where White accidentally bumped a delicate stalactite formation. The tiny narrow straws broke from the ceiling and came twinkling down to the floor like icicles.

"It was a huge faux pas," White says. "Breaking a formation is like sacrilege. One of the leaders said, 'Well, we obviously have some people here that shouldn't be.'"

White was humiliated. But he was also angry.

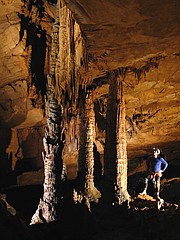

"I mean, geez! Then show me how to do it right! People can't know what they don't know," says White - now an avid caver. He describes caving as mountaineering in reverse. A mountaineer's objective is to reach the highest peaks. A caver's objective is often to reach the deepest depths. "After you summit a mountain, gravity is working in your favor. You just have to descend. But when you reach the bottom of a cave - say, 400 feet deep - that's the easy part. Now you have to get out," says White, who is also the Southeast Region coordinator for the volunteer-based National Cave Rescue Commission.

The Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia caving community, known as the TAG community, represents the largest concentration of caves and includes the deepest underground pitch in the continental U.S. So there are countless opportunities for a novice caver to require rescue. A novice, in the caving community, is known as a "Joe Spelunker."

The caving community is famous for being exclusive. Though cavers prefer to call it tightknit. They look out for their own. They take their sport seriously.

For some, caving is like a religion.

"We call it the Church of Karst," says Kim Bodenhamer Smith, local caver and board chair of the Chattanooga Grotto. Like most other caving clubs, the local grotto is comprised of individual members of the National Speleological Society. Anybody can join. It is only a matter of attending meetings and paying dues.

Over a dozen grottos exist within the TAG region. Smith says the Chattanooga Grotto is the most organized caving club of which she's been a member. White and his partner, Amber Lehmann, are members too.

"We're more organized than any church," says Smith.

In order to protect their temple, seasoned cavers want spelunkers to know a few things before setting out on an underground adventure of their own.

More Info

How to get startedYou wouldn’t invest in expensive climbing gear before you hit the climbing gym to make sure it’s a sport you love, says White. So before you commit too much time and money to your local grotto, it can be beneficial to get a couple caving trips under your belt. Georgia Girl Guides, or G3, is a local adventure-guiding service located on Lookout Mountain. G3 leads wild cave tours and group cave tours that feature stunning cave formations, underground rivers and more. Their tours can accommodate those age 6 and up. Outings last 1, 2 or 4 hours. Along with the guided exploration, participants receive an introduction to cave geology, conservation and safety, as well as information on how to connect with local grottos.To find out more about Georgia Girl Guides visit georgiagirlguides.com.

How to Stay Safe

The "Golden Hour" is a medical concept that says the first hour after a traumatic injury is the most important in receiving successful treatment.

"Cavers talk about the 'Golden Day,'" White says, explaining, "It's akin to the '10 to 1' rule. If you've traveled one hour underground, it will take 10 hours to get you out. That's not a hard and fast rule. But it's a good general rule," he says.

The most common injuries sustained in a cave, says White, are slip-and-fall related sprains or broken bones. Other common injuries include head injuries and hypothermia. The most common rescue, he says, is not so much a rescue as it is a search - "the guy with the baseball cap and flashlight who goes into a cave, his flashlight goes out and he can't find his way out."

According to National Speleological Society code, each caver is required to carry three sources of light. The primary light is mounted to the helmet. Smith says a helmet is the most important gear when it comes to responsible caving. Some passages are the size of an amphitheater, but others are narrow squeezes. "Inevitably, you are going to bump your head," she says.

Smith suffered hypothermia during her first cave adventure. It was a "swimming cave," she says. She wore a wetsuit, but still, her body temperature started to drop. Luckily, she was accompanied by cavers trained in rescue, who noticed when her lips turned blue.

Overheating is as serious a risk as hypothermia, adds Smith. Cavers should never wear natural fibers such as jeans or cotton, which tend to hold moisture and heat. Instead, they should wear moisture-wicking material such as polypropylene, nylon or polyester.

"There are things that people do every day without thinking, that you just can't do in a cave. It's a different world," Lehmann says.

Jumping, for instance. Or, remembering the three-points-of-contact rule, which states three points of the body must be touching immovable objects when traversing uneven ground. "Two hands and a foot. A shoulder, a foot and a butt," Lehmann explains.

"And watch the person behind you. You are always responsible for the person behind you."

The sociology of caving is different than other sports, she says. "It can be a life or death situation, and you have to rely on the people you are with."

More Info

The hush, hushCavers love to talk about caving. But cavers do not love to disclose their caving locations. Although this is commonly interpreted as elitism, in fact, it usually has to do respecting landowners’ property rights. Many caves are located on private property, says White. Or a cave might be owned by the Southeastern Cave Conservancy but adjacent to private property. The conservancy may have a relationship with that landowner that a common caver does not. Similarly, veteran cavers often have established relationships with those landowners. White says protecting that relationship is important to the caver, as it is important to the health of the cave as well as the private property. “Say Joe Farmer has a cave on the back of his 40-acre farm. He doesn’t need people driving across his cornfield every weekend,” White says.

How to protect fragile ecosystems

Part of cavers' protectiveness is that caves host fragile ecosystems and rare wildlife. "Caves are a non-renewable resource," says White. For example, there are salamanders and spiders. In cave lakes, there are fish and crayfish.

"When you put your hand on a wall, you have to make sure there isn't a bat there," says Maureen Handler, local caver and chairwoman of the SERA Karst Task Force, a regional nonprofit dedicated to cave conservation and watershed cleanup.

Bats are a hot topic for cavers. Since 2006, white-nose syndrome has killed an estimated 6 million bats in the Eastern U.S. In part, the spread of this fungus has been linked to human activity.

To help protect bats, or as Smith calls them, "cavers' little friends," cavers should decontaminate their gear after every caving trip. This can be achieved either by soaking gear in water that is 122 degrees Fahrenheit for at least 15 minutes, or by wiping gear down with Formula 409 antibacterial cleaner, Lysol disinfectant wipes or bleach, according to the United States Fish & Wildlife Services.

In addition to cave conservation and education, SKTF organizes caving trips dedicated to picking up cave litter, which, Handler says, is often discarded batteries. Occasionally, SKTF participates in graffiti removal. However, this cleanup can be tricky.

"If you can easily get to a cave, then Native Americans could easily get to it as well. We have to be very careful that we're not destroying historic stuff," Handler says.

One way to avoid disrupting ancient artifacts is by staying on established trails. "Elephants tracks," Handler calls them. Although rare, it is possible for a caver to see prehistoric footprints imprinted in the dirt or fossils stamped in cave walls.

"Once, I saw a shark's tooth on the ceiling of a cave," says Smith. "I just stopped and was like, 'God's Time!' I thought, 'Wow. We are all just a flash in the pan.'"

Chattanooga is privileged to be part of such a vast and stunning cave system. But caving is a sport that comes with big responsibility and risk. To understand karst, one must see the big picture, says Smith. The above and the below; the light and the dark.

"That can take an act of faith," says Smith.