Toya Morris still remembers the sounds her toddler made the first time air stopped reaching his lungs. She heard the wheezing in his chest, and watched him struggle to cry. He couldn't utter a word.

"I had to just rush him to the hospital because I did not know what was going on," said Morris.

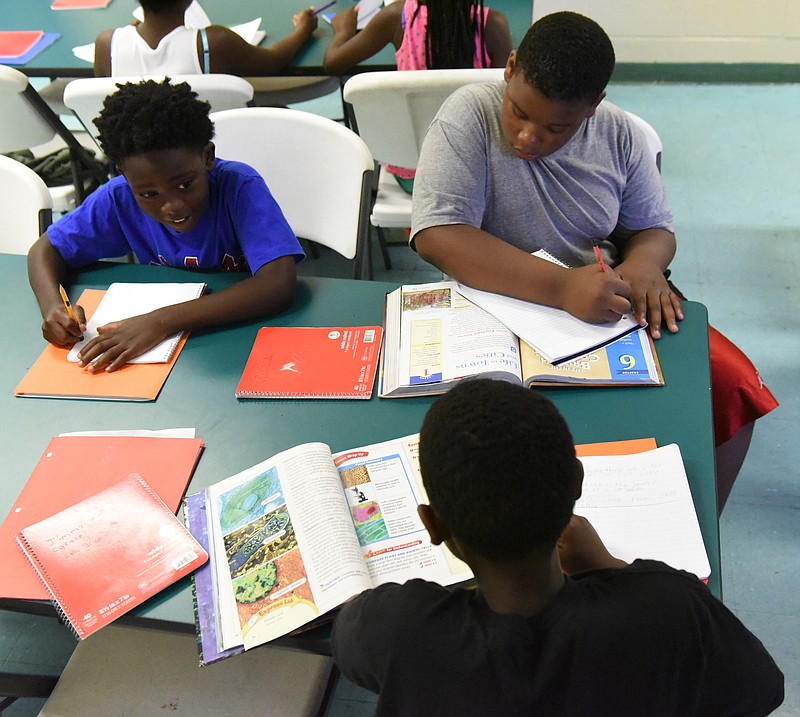

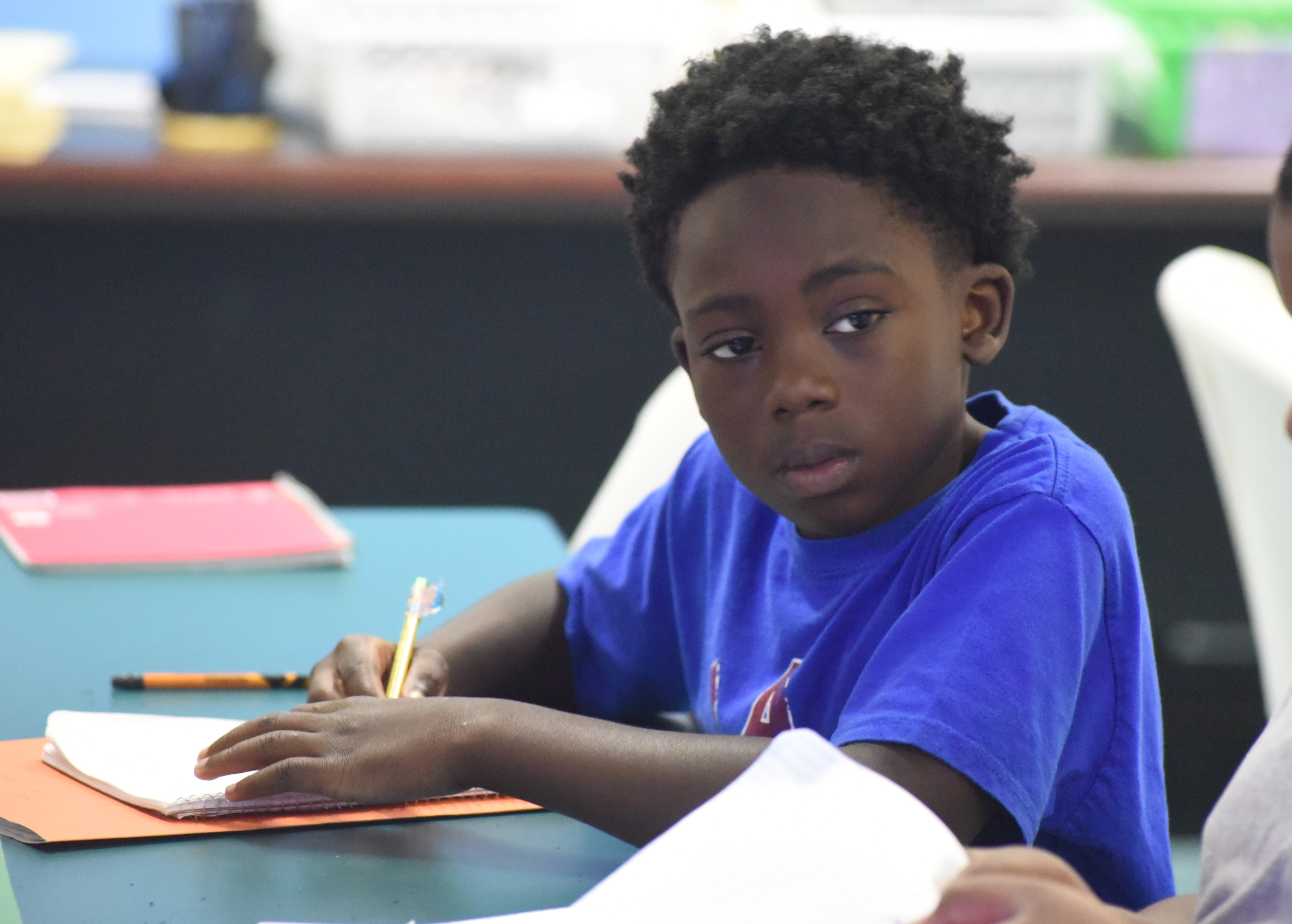

It has been about eight years and several more hospital trips since Toyriec Morris, now 10, was first diagnosed with asthma. Since then, he and his mother have learned the rhythm of daily breathing treatments. The inhaler is always close by. Toyriec can now play soccer with his friends, and splash in the pool.

More Info

BY THE NUMBERSTENNESSEE› 11.5 percent — Prevalence of asthma among children. That’s up from 9.5 percent in 2007.› 78,681 — Number of Tennessee school children with asthma in 2013-14› 85 percent — How much the number of students diagnosed with asthma has increased since 2004. That year, 38,676 student were diagnosed with the condition.› 43 percent — Rate of children who actually have an asthma treatment plan.*53 percent — Rate of Tennessee school systems that reported “no” when asked if a nurse was present all day in schools where a student might need asthma medication in an emergency situation.› 14,373 — The number of Tennessee children who received an emergency asthma treatment from a school health care provider in the 2013-14 school year.› 32.7 percent — The percentage of children who live in a household where someone uses tobacco. The national rate is 24.1 percent.› 14,530 — The average number of asthma-related ER visits. The average charge for an ER visit was $1,953 in 2012, while the average per visit charges for inpatient hospitalization for asthma was $14,435.› $53.7 million — Total hospital charges for childhood asthma in 2012› In 2011-12, Tennessee had the third-highest current childhood asthma prevalence behind Delaware and Alabama. Tennessee had the 15th highest lifetime childhood asthma prevalence rate as well.Sources: Tennessee Department of Health; Tennessee Department of EducationGEORGIA*9% — Prevalence of asthma among children in 2010.*13.9% — The prevalence of children with asthma whose family annual household income was less than $15,000. Among children from families making $50,000, the rate is significantly less — 8.9 percent.*$32.8 million — The cost for asthma-related ER visits statewide. The cost for hospitalizations was more than $27.8 million.*191 per 100,000 — The overall asthma hospitalization rate for black children. That’s more than double than that of white children (78 per 100,000).*25,930 — the total number of asthma-related ER visits.*56% — the percentage of children with no asthma action plan*55% — The percentage of children with asthma who missed at least one day of school in the previous 12 months.Sources: Georgia Department of Public Health

But his mother, who was also recently diagnosed with asthma, doesn't feel they are out of the woods. A hot day can make her child's chest squeeze tight. Tree pollen can start him wheezing again.

Asthma threatens the most fundamental human function: breathing. And yet it is so common it has gained the reputation as a trivial disease - a problem long-conquered.

But the illness is far from conquered in Chattanooga. While the city touts overcoming its old "dirtiest city in America" moniker, it has still been named in top 10 "Asthma Capitals" of the U.S. for the past six years.

The list, created each year by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, ranks cities based on pollen, pollution, secondhand smoke, poverty, number of uninsured families and emergency room visits. Tennessee has consistently had more cities at the top of the list than any other state.

Such an environment especially affects kids. While an average of 8.3 percent of children suffer from asthma nationwide, Chattanooga's rate is closer to 12.5 percent, according to the he Pediatric Healthcare Improvement Coalition of Tennessee.

A casual attitude towards asthma bothers Hamilton County Schools Health Coordinator Sheryl Rogers, who grows solemn as she discusses the 2011 asthma-related deaths of two Chattanooga school children - an elementary-age child and and middle-schooler.

"It is what sparked my push to get more outside help with asthma," Rogers said. "It's bad. It's worse than people think. It's a disability, but one that is often invisible until it gets bad - so parents don't know how to treat it."

The rate of Tennessee schoolchildren diagnosed with asthma has risen 85 percent since 2004 - an increase that is partially due to better record keeping, officials say. But the increase in child ER visits has also increased 12.5 percent since 2003.

T.C. Thompson Children's Hospital at Erlanger alone has treated 804 severe asthma attacks in its ER in the last year.

Schools often resort to the ER when a child has an attack and a parent is not available. Last year, 14,373 children in Tennessee received emergency treatment at school for asthma.

Around 10 percent of Hamilton County school kids take medication or use inhalers. But there are many others who do not have medication on hand. In a state report issued this year, just 43 percent of Tennessee school children with asthma have a treatment plan - something state officials said needs to change.

And the price tag is expensive. Hospital charges for asthma-related events came to $53.7 million in Tennessee in 2012. In Georgia, hospitals charged $60.6 million for asthma cases in 2010.

Add to that the cost of children missing school and parents missing work to come get them, and the illness has "a very broad impact," said Dr. Michael Warren, director of maternal and child health for the Tennessee Department of Health.

Much of that is unnecessary spending, Warren said, because asthma is manageable. But asthma maintenance is a major area where families fall through the cracks, especially in low-income neighborhoods. It's a problem that a group of Chattanooga doctors, led by the Pediatric Healthcare Improvement Coalition of Tennessee, is trying to address this year.

In the coming months, the group hopes to see more community education meetings, better coordination between parents and school nurses, and even school-based primary care clinics.

"It's really one of those things we need to - and can - effectively and inexpensively hammer out," said Dr. Allen Coffman, a pediatrician and president of the coalition. "We've had some success with this in breastfeeding. There are ads on billboards and at bus stops. We need to immerse the community in support for this, too."

A CITY FULL OF TRIGGERS

Chattanooga's air quality has vastly improved since the days of its staggering pollution rates a generation ago.

Still, the city's continued level of industry, combined with its basin-like topography, its climate, and its wide spectrum of plant life create an arsenal of asthma triggers, doctors say. The fact that one in four Tennesseans smoke only makes it worse.

Children living in low-income homes have much higher rates of asthma, said Warren. Mold, dander, cockroaches or a lack of air conditioning all set off reactions.

But even with Chattanooga's environment, much of the emergency care is preventable, officials say.

A major problem, said Warren, is parents' grasp on medication. While parents may be familiar with "rescue" medication for an asthma attack, they often fail to give their child daily "maintenance" medications.

"Asthma sounds like an easy diagnosis, but it's just not," said Dr. Joel Ledbetter, a pediatric pulmonologist at Children's Hospital. "It's like any chronic illness - all about maintenance and therapy."

Ledbetter hopes to soon reopen a pediatric asthma center at Erlanger to provide better education. The hospital's former center closed when the physician who ran it left.

Watching families show up repeatedly to the ER can feel like "trying to drain the ocean with a spoon," Coffman said.

But he had an eye-opening realization a few years ago. Within the same week, he had a conversation with nurses who were complaining that parents didn't take asthma seriously, and then one with mothers of asthma sufferers who were frustrated that they felt so helpless.

"There is a gap in the provider-parent-child connection," said Coffman. "It's a place where as providers we have to start doing things better."

Insurers agree. Starting this year, TennCare is changing its reimbursement model for doctors who treat asthma attacks. Instead of just paying per treatment, the program will reward or penalize doctors based on the patient's long-term outcomes.

FINDING SOLUTIONS

Earlier this year, Toya Morris headed to the Bethlehem Center in Alton Park for a community forum. The meeting, called "Breathe Easy," was a chance for parents in Chattanooga's urban neighborhoods to talk about the asthma struggle.

Morris listened as another mother described her daughter's repeated hospitalizations. Morris then shared how she found an asthma doctor for Toyriec, and how regular care helped them avoid the hospital.

"I tried to tell her that it doesn't have to get that far," Morris said.

Coffman wants to see such support groups held more regularly. But awareness is just one front. A more dramatic solution, he says, is in school-based clinics: Doctors' offices that are set up at schools, so children can get more consistent care.

Access to care is the main goal in such a model, but so is education for "the next generation of parents," Coffman says.

Multiple studies published in medical journals have shown that school-based health clinics bring down the number of ER visits among children and significantly reduce the cost of missed work.

"Children with asthma need a primary care medical home," said Warren. "It's amazing how that relationship can drastically improve their quality of life."

Hamilton County school officials have been supportive of the Pediatric Healthcare Improvement Coalition of Tennessee's work to create school-based clinics, which would be contracted out with area providers. Coffman hopes to see some set up as early as next year.

"But Chattanooga is a smart community, we need to build resources and systems to deal with this," he said. "This can't be something a few pediatricians want to fix. We've been very purposeful that this is something Chattanooga wants to fix."

Contact staff writer Kate Belz at kbelz@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.