Clara Louise Edwards, the Ringgold, Ga., foster mom accused of killing a 2-year-old girl, is going back to court.

Superior Court Judge Ralph Van Pelt Jr. this week granted a prosecutor's motion for a new trial, allowing the state to retry Edwards on a charge of felony murder. Last month, a jury convicted Edwards of first-degree cruelty to children but acquitted her on a charge of malice murder - Georgia's way of alleging the killer intended to take a life.

After the jury deliberated for 11 hours over three days, Van Pelt also declared a mistrial on a charge of felony murder because the jury failed to reach a consensus on that count. Van Pelt was supposed to sentence Edwards - who faces five to 20 years in prison for the cruelty to children charge - on March 25.

But at the request of Lookout Mountain Judicial Circuit Assistant District Attorney Alan Norton, Van Pelt has delayed the sentencing hearing indefinitely. Instead, Norton and District Attorney Herbert "Buzz" Franklin will try to convict Edwards of felony murder in a new trial, which Van Pelt scheduled for Aug. 8.According to Georgia law, a person commits the offense of felony murder when he or she kills somebody while committing a separate felony, even if the murderer did not intend to take a life. It carries a sentence of life in prison.

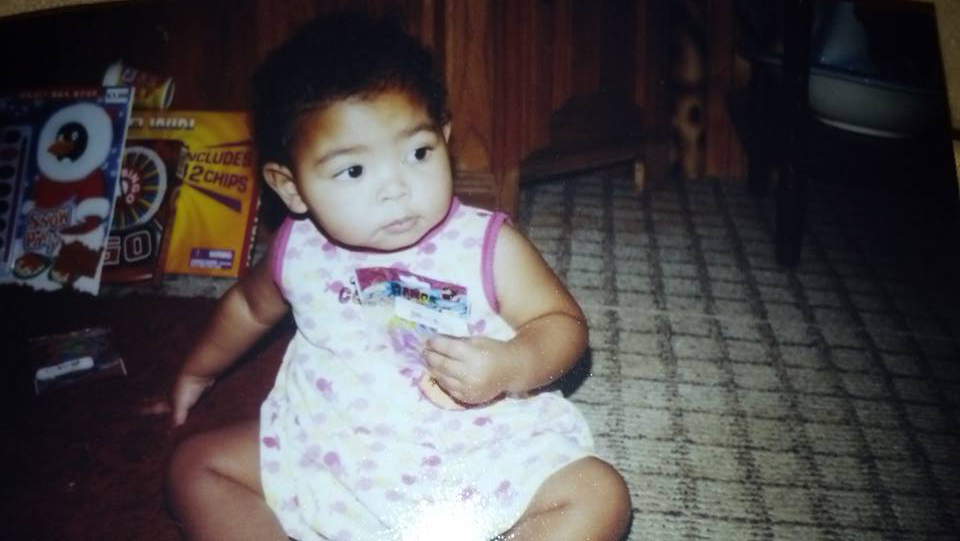

In December 2013, Edwards told investigators she found her 2-year-old foster child, Saharah Elise Weatherspoon, unconscious in the toddler's bedroom. She said Saharah slipped down the stairs earlier that day, but Edwards thought the girl was fine.

Edwards, 60, took Saharah to T.C. Thompson Children's Hospital at Erlanger, where doctors said they found two blood clots on her brain. One was a recent blood clot, the other from weeks or months earlier. They also found bruises splotching Saharah's stomach, back, arm and face.

Edwards' attorney, Dan Ripper, argued in court that the injuries didn't necessarily mean Edwards hurt Saharah, even though day care workers and members of Edwards' church had reported concerns of abuse to the Division of Family and Children's Services. Before Edwards took Saharah in, Ripper pointed out, police arrested Saharah's biological father on allegations he stabbed her biological mother and tried to burn his children alive.

Ripper said Saharah came to Edwards with developmental delays and struggled to walk. She fell often, and she bruised easily.

"She did not kill this child," Ripper told the jury during his opening statement. "We believe the proof will show this child was abused since she was born. And when she unfortunately had an accident that day, that was the last straw."

Chris Lambert, one of the jurors in the case, told the Times Free Press he initially believed Ripper's version of events. He voted to convict her of cruelty to children early in the jury's deliberation, figuring that even if Edwards didn't directly hurt Saharah, she at least neglected her. To Lambert, that was bad enough.

But Lambert felt uncomfortable convicting Edwards of murder when nobody saw her abuse Saharah. If nothing else, he figured, Ripper's defense at least seemed plausible: The child could have fallen often, and she could have bruised easily.

"How that happened," he said, "no one will really know."

But after several hours of deliberation, Lambert changed his mind. Along with nine other jurors, he voted to convict Edwards of felony murder. Two jurors were steadfast, though: They would not convict her on that count.

The circumstantial evidence swayed Lambert - the bruises, the long-term blood clot, the amount of time it took Edwards to bring Saharah to the hospital. By her own statements to the police, Lambert said, Edwards found Saharah passed out around 9 on the night in question. Lambert said the medical records showed she didn't check the child into the hospital until after midnight.

Edwards told investigators that after she found Saharah unconscious, she panicked. She didn't call 911. She ran around the house, changed clothes, put the child into the car and began to drive to the hospital. She called her husband, who was on his way home from work. He told Edwards to wait for him. She returned to her driveway.

"It never should have happened that way," Lambert said. "She very well could have been in a panic. But when a child is unresponsive, you should call 911 immediately. And you should never turn around and go back home. I thought about that for a long time."

Still, by the third day of deliberations, he said he and the jurors realized they would not reach a consensus.

Contact staff writer Tyler Jett at tjett@times freepress.com or at 423-757-6476.