It took the hard work and coordination of about 400,000 people to put Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon 50 years ago.

Among them were Bill Baker and the workers of the Arnold Engineering Development Center at Arnold Air Force Base in Tullahoma, Tennessee. They were responsible for testing the Apollo program's spacecraft.

Baker still works there as technical director of the Test Operations Division of what is now known as the Arnold Engineering Development Complex.

He got his first taste of the work being done there when he was a freshman at Mississippi State and joined the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences. The group was planning a field trip to a place he'd never heard of - Arnold Engineering.

"It just blew me away," he recalled. "I didn't know this kind of stuff was going on right here in Tennessee."

Baker's first job at Arnold Engineering - where testing for Apollo was already under way - was as a junior engineer in a test and technology group testing several types of technology including "the Apollo escape module, the rocket and the capsule," he said.

ARNOLD ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT COMPLEX

Arnold Engineering Development Complex was dedicated in June 1951 by President Harry Truman and named after 5-star General of the Air Force Henry “Hap” Arnold, visionary leader of the Army Air Forces during World War II and the only airman to hold the 5-Star rank. Virtually every high performance flight system in use by the Department of Defense today and all NASA manned spacecraft have been tested by AEDC. Today, the Complex is testing the next generation of aircraft and space systems. To learn more about AEDC, visit www.arnold.af.mil.

The escape module had to work perfectly, because it was designed for use when everything had gone catastrophically wrong and the crew needed to get away from the main rocket and remain stable.

"It had to be flying straight for the parachutes to operate," he said. "It was a system we hoped that we would never use and we never did."

Baker also assisted in testing the rockets that would lift the ascent vehicle off the lunar surface, dock with the orbiter and return the astronauts to earth.

"We did almost 90,000 hours of testing at AEDC on this Apollo system," Baker said.

INSIDE THE PROGRAM

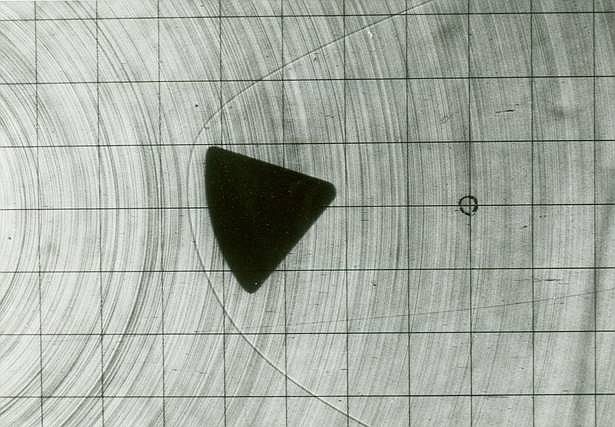

The NASA-designed test program called for Arnold Engineering to collect data on aerodynamic heating, stability and loss of exterior material during spacecraft reentry, interaction between separating components and aerodynamic loading throughout the flight process, and to help address problems that arose during development, according to a statement from Arnold Engineering.

Between 1960 and 1968, more than 3,300 hours of wind tunnel tests were conducted at Arnold Air Force Base, representing more than 30% of the total wind tunnel work performed for the Apollo program. During the period, more than 1,700 rocket firings were performed at the Tennessee facility.

Even before Project Apollo was officially launched, testing that eventually would support spacecraft development started in 1960. In June that year, the first aerodynamic test was conducted on a scale model of a proposed Saturn launch vehicle in the facility's 1-foot transonic wind tunnel, and in January 1961, engineers tested the proposed Saturn launch vehicle the same year Project Apollo was established.

The launch vehicle wound through several configurations, eventually resulting in the Saturn V rocket that took men to the moon. The first Saturn rocket was launched from Cape Canaveral in October 1961 after more than 600 hours of testing in Tullahoma.

In 1962, NASA determined that the lunar missions would be carried out with a single, three-stage rocket with a manned capsule, and also decided that a smaller, lighter Lunar Excursion Module, called the "LEM," would be used to land on the moon's surface and return to the orbiting capsule.

By 1963, tests on the LEM's descent engines and the engine for the Saturn IB and V rockets were under way.

LUNAR MODULE BY THE NUMBERS

The NASA/Grumman Apollo Lunar Module after descending to the lunar surface from lunar orbit provides a base from which the astronauts explore the landing site. It enables the astronauts to take off from the lunar surface to rendezvous and dock with the orbiting Command and Service Modules before the return voyage to earth.22 feet, 11 inches: Height, legs extended31 feet: Diameter36,100: Approximate launch weight with crew and fuel75 degrees: Crew cabin temperature160 cubic feet: Habitable cabin spaceSource: NASA, Grumman

In 1965, the Saturn V's retro rockets, used for braking, developed a then-record 100,000 pounds of thrust in the test cell at AEDC.

In 1966, tests were conducted on rocket engines for the LEM and other stages of the Saturn V, as well as tests of the scale-model Apollo command modules.

From June 1965 to June 1970, 340 rocket engines were fired in the single largest test program ever conducted at the Tennessee facility to rate the Saturn V upper stages for human flight.

ONE GIANT LEAP

The testing done at Arnold Engineering helped to lead America's astronauts to 10:55 a.m. on July 20, 1969, when millions watched on television as Armstrong exited the lunar module, dubbed the "Eagle," and said to the world, "That's one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind."

That day stands out prominently in Baker's mind.

"My wife and I went to a friend's house. He had a color TV and, of course, we watched black and white images on his color TV of the moon," Baker said of those heart-stopping moments played out on television screens and radios around the world.

"We were sitting in the living room watching as Armstrong came down the ladder and walked out on the moon," he said. "As we watched the reporting of the descent to the surface, you know we were holding our breath like everyone else around the country till they got to the ground.

"When he said 'Tranquility Base here,' that was it. Everybody just cheered," Baker said.

In the Apollo missions that followed and as men returned to the lunar surface, the accomplishment still amazed him.

"I remember vividly going out in the yard one night; we had a full moon and there were men walking around up there," he said. "I thought 'Gee whiz. We've got people walking around up there.' That was just a really exciting thing."

Baker will mark Saturday's 50th anniversary of the moon landing with local school children at Tullahoma's Hands-On Science Center. He hopes to share his knowledge while inspiring them to turn their own eyes toward the sky.

"This is an exciting field to be working in and there's so much going on right now in aerospace and in preparations for going back to the moon and going to Mars," he said, adding there's "so much opportunity for young people to get into the technical sciences."

Baker envisions renewed excitement about space and more historic milestones ahead.

"It's some amazing times and maybe we'll get to watch another landing in the pretty near future," he said.

Contact Ben Benton at bbenton@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6569.