Nearly a hundred people gathered in East Chattanooga on Saturday - despite rain and fog - to launch a grassroots coalition set on pressuring Chattanooga City Council members to refuse support for the sale of the city-owned former Tubman public housing site unless the buyer signs a community benefits agreement.

The meeting - hosted by Hope for the Inner City, Unity Group of Chattanooga, Chattanooga Area Labor Council, Chattanooga Organized for Action, Glass House Collective, Urban League of Greater Chattanooga and Accountability for Taxpayer Money - was held at Hope for the Inner City. It was spurred by shared frustration over the recent industrial zoning of the former Harriet Tubman site, which was purchased from the Chattanooga Housing Authority by the city of Chattanooga in 2014. The group is now seeking to start a community-led development process with the city's support.

"We are all at the table hearing the same information so we can work together and work together constructively," said Quentin Lawrence, deputy executive director at Hope for the Inner City.

City administrators and Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce staff have said that light manufacturing is the best use of the site because East Chattanooga needs jobs. They also said businesses hadn't been interested in the site because its zoning had not been changed from residential to industrial.

However, residents were surprised when the city began pushing to quickly rezone the site not long after launching a city-backed, community-wide planning process to determine the future of East Chattanooga, including the Tubman site. Many feared the move would undermine efforts to engage East Chattanooga residents - who, for the most part, have not benefited from the last few decades of economic growth in and around downtown - in the planning process.

Others wanted the city to consider mixed-use zoning, which at one point had been recommended by Chattanooga-Hamilton County Regional Planning Agency staff.

Anne Barnett, a representative from Stand Up Nashville, spent the first half of the meeting explaining to the crowd how a coalition in Nashville organized and aroused enough community-wide engagement to win support from 31 of Nashville's 40 council members and secure the city's first CBA last year.

The Nashville CBA targeted the developers who had been working to cut a deal with city officials to purchase city-owned land in order to build a Major League soccer stadium, as well as an adjacent commercial/residential development. Their CBA required the developer to meet goals related to affordable housing, jobs and workforce development and community amenities. For example, Barnett said the CBA called for 20 percent of all housing built to be affordable and for the majority of those affordable units to be three-bedroom family units and not small, cheap studio apartments.

In Tennessee, and in many other southern states, state law says city governments cannot require businesses to sign and adhere to CBAs because many of the requirements typical of CBAs infringe on developers' right to do business as they please. This is not the case in many other states. This means city officials cannot be involved in negotiations.

However, CBAs signed when developers face opposition from city councils - hoping to appease angry constituents - are considered legally binding contracts. The only problem for community coalitions who win a CBA is that they have to have the funds to take the developer to court if they violate the terms of the agreement, which can be a challenge, Barnett said.

"This is a lot of work, you guys. I want to be real. It is a huge commitment," said Barnett, who credited their success to all the people who had children and jobs, yet still gave their time. "We have so much more power than we think we do. We have more power together than we do apart. Those are two things that I always come back to."

After learning about Nashville's experience, the large group - diverse in terms of age, race and socioeconomic background - broke up into smaller groups to begin discussing what kinds of community benefits could be tied to the sale of Tubman.

Organizers said the next step will be adding the support of more local organizations to the coalition and canvassing East Chattanooga with surveys to see what residents who didn't attend the meeting might want in a community benefits agreement tied to the sale of the Tubman site.

This type of broad-based community organizing has, for the most part, been absent from the city since Chattanooga Venture - the foundation-backed nonprofit that sparked the renaissance with its community-wide visioning process - lost its funding in the 1990s, just as it was beginning to train neighborhood leaders how to organize and represent their interests at City Hall.

Several city staff members and council members were present, mingling, looking on. The energy in the room was palpable.

"To see what happened in Nashville and what they were able to accomplish, I think it has lit a fire in Chattanooga, and I am very excited," said James McKissic, who led the city's office of multicultural affairs for six years before leaving, earlier this year, to head the Urban League of Greater Chattanooga.

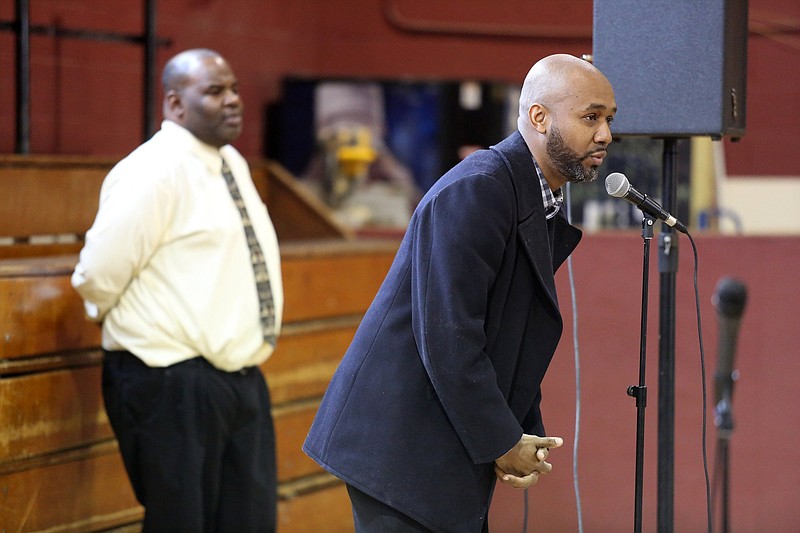

At the close, Eric Atkins, head of The Unity Group, came to the microphone, pointed out the officials present and asked if they wanted to speak.

Councilman Anthony Byrd, who has faced harsh criticism in recent months for not doing more to oppose the industrial rezoning of Tubman, rushed to the front of the room.

"There will be times that we disagree and we will have some uncomfortable conversations. That is how families work," he told the crowd. "I have been enlightened. Please come back. If we don't do this, no one else will.

"You have my vote."

Contact Joan McClane at jmcclane@timesfreepress.com.