A few years ago, Tiffany Herron was standing on M.L. King Boulevard, listening to stories she'd never heard before.

She'd signed up for Chattanooga Organized for Action's people's history tour: a downtown tour, with guides, that spotlights people and places excluded from the city's mainstream narrative.

Her tour guide spoke about old landmarks on what was formerly Ninth Street: our city's first integrated church; the Martin Hotel, featured in green books; a black-owner newspaper published by a former slave.

Then, she heard another story - about four African American women from Chattanooga who changed America.

In 1979, Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke traveled to Sale Creek for a cross burning. Some 500 people came. One of them, Bill Church, so roused, would soon create the Justice Knights of the KKK.

On April 19, 1980, Church, 23, and two other white men - Larry Payne and Marshall Thrash - drove down Ninth Street in a red Mustang with two shotguns, more than five dozen shells and a letter about starting a race war.

Near the railroad underpass, the men tried to burn a cross out of 2x4s.

They turned back down the road.

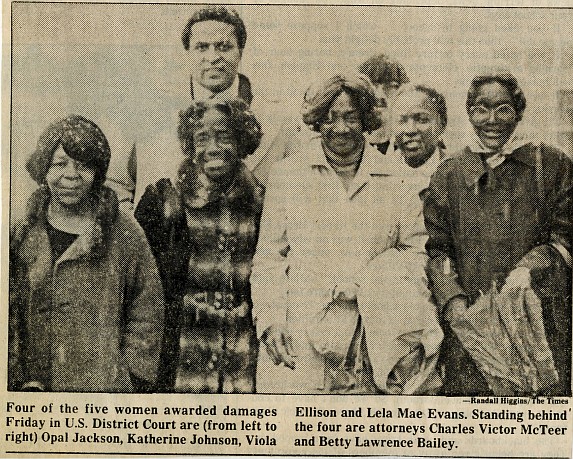

At the same time, four African American women - Viola Ellison, Lela Mae Evans, Katherine O. Johnson and Opal Lee Jackson - walked out of a club called The Stack.

Thrash fired a shotgun out of the Mustang.

The four women were hit.

They were injured - one woman had more than 100 shotgun pellets in her leg - but not fatally. A fifth woman, Fannie Mae Crumsey, is struck by glass while bent over, working in her flower garden. (Had she been standing, her lawyer later said, she'd have been decapitated.)

Police locate and arrest the men.

Months later, an all-white jury acquits them of attempted murder charges; Thrash, the shooter, is sentenced on lesser charges to nine months in jail. (Officials later released him after three months, citing good behavior.)

Black Chattanooga explodes with rage. President Jimmy Carter asks the Rev. Jesse Jackson to come to Chattanooga.

"Businesses are firebombed. Marches and confrontations multiply across the city," the tour guide said. "Other Klan leaders from across the U.S. come down in an attempt to antagonize and bomb protesters. One newspaper story tells of a police car chase with Klansmen throwing sticks of dynamite at the cop car."

Yet the women will not be defeated.

They decide to sue the Klansmen in civil court.

In February 1982, they win.

Their victory - $535,000 awarded in damages - created a new anti-Klan strategy that would influence lawyers across the nation. (Some 75 years prior, Noah Parden became one of the first black lawyers to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court, which means African Americans in Chattanooga have twice changed the nation's legal landscape.)

Yet standing there on King Boulevard, Herron realized the sad truth: she'd never heard this story. Her friends hadn't, either.

"How does no one know about this?" she said. "Chattanooga should be proud of them."

A creative writing graduate student at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, she decided to change that. Herron began research in order to write a novella or essay based on the women.

She expects an early draft next year. Anyone connected at all to this story may contact her at 423-987-6820 or tiffanyjherron@gmail.com.

"These women," she told her professors, "deserve acknowledgement in a way which evokes appreciation and inspiration."

Her research took her to New York City, where she met with Randolph McLaughlin, who represented the women in civil court.

Near the end of their conversation, she asked:

Would you come to Chattanooga to speak?

Yes, he said.

If you're going

“Black Heroines for Justice” begins at 5:30 p.m. at the Bessie Smith Cultural Center on Thursday, Feb. 20. For more information, contact Tiffany Herron at tiffanyjherron@gmail.com.

This Thursday, Feb. 20, McLaughlin returns to Chattanooga to speak about these women and the history they made.

The free event, called "Black Heroines for Justice," begins at 5:30 p.m. at the Bessie Smith Cultural Center.

"It was the first time that African Americans or anyone, frankly, had successfully sued the Ku Klux Klan," McLaughlin said.

McLaughlin is a joy to speak with, a wellspring of wisdom, legal clarity and Chattanooga history.

* His strategy was based on Reconstruction-era anti-Klan laws that had been buried and forgotten, especially by Southern states.

"We found this 1871 statute," he said. "It was called the Ku Klux Klan Act."

* Researching the potential jury pool, they conducted an opinion poll on white beliefs about the KKK.

"White residents of Chattanooga and its environs - thought the Klan was a good thing," he said.

* During the trial, held in the federal building, McLaughlin remembers this mural on the courtroom wall depicting a sunbonnetted white woman, holding a white baby, as Confederate soldiers limp home from the war. In the background, black Southerners pick cotton.

"Those black people were slaves," he said. "And I'm trying this case against the Ku Klux Klan, looking at slaves and Confederate soldiers marching."

* McLaughlin sees connections between then and today.

"For every period of advancement, whether the Civil War, Reconstruction, the civil rights movement or the election of Barack Obama, it always leads to a backlash by angry disaffected whites who see their country becoming something they don't recognize, which means a country that's diverse and black folks have some power," he said. "I think the current environment we're in now is just as ugly as what happened in the 1870s."

Yet, hope endures.

"In each of those eras, black and whites came together to resist white supremacy," he said. "Throughout our history, African American women have always stood up and fought. Always."

David Cook writes a Sunday column and can be reached at dcook@timesfreepress.com.

View other columns by David Cook