In Jim Ledbetter's opinion, wolverine meat was the worst.

And he tried it many ways: grilled, boiled, canned; ground into sausage.

"Even the dog wouldn't eat it," he remembers, describing its taste, 49 years later, as a cross between rot and urine.

But, he says, living in British Columbia's Coastal Mountains - where he was 60 miles from the nearest town and snowed in for months at a time - "it was meat, so you didn't waste it."

"I would have liked to stay there forever," Ledbetter then adds wistfully.

***

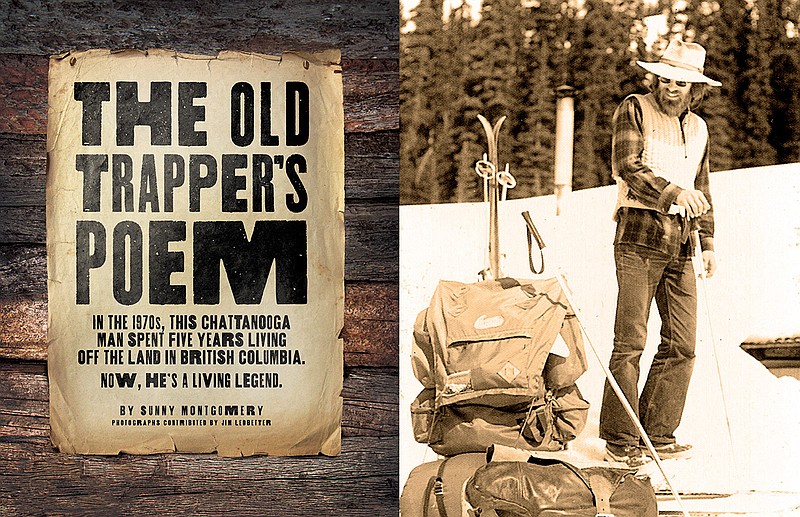

In 1971, Ledbetter and his college sweetheart, Jackie, had just graduated from Middle Tennessee State University. She'd studied music; he'd studied art and had aspirations of becoming a jewelry-maker. But Ledbetter had another dream, too: to leave society and live off the land.

"I've always been fascinated by mountain people that were able to make a living off their ingenuity," he says. "The very first Halloween costume I remember choosing as a young child was 'moonshiner.'"

Ledbetter's father grew up in Southeast Appalachia during the Great Depression, and had taught Ledbetter and his brother to fish and hunt squirrel and rabbit at a young age. For summer vacations, he remembers, his father would pile the family into their station wagon and just start driving. "Usually heading to the beach or the mountains, stopping somewhere along the way to sleep. [We] seldom went to the same place twice.

"Taking a trip, not knowing the destination, was just something I was raised with," Ledbetter says.

So after graduation, Ledbetter and Jackie, now his wife, packed his VW bus with art supplies, hand tools and a couple of books about backcountry living, and headed west.

***

Alaska had always appealed to Ledbetter, and the couple set their sights on the remote state's expansive wilderness. En route, they passed through British Columbia, stopping one night to make camp along the Frazier River.

One night turned into two months. The couple met some townsfolk, moved into a one-room cabin and found work as ranch hands. Through a neighbor, they learned of a fur trapper who was ready to leave his route and move back to town.

Trappers in the fur trade often spend months at a time following remote routes through wild terrain. In British Columbia, the government owns the vast majority of land; however, it will lease land to trappers, permitting them to hunt and build cabins along their traplines. And this particular trapper wanted to sell his permit, which cost $500 and would allow Ledbetter and Jackie to build.

"That was all it took to have us settle down," Ledbetter says.

Following a long dirt road out of town and a steep trail into the mountains, Ledbetter and Jackie found an old camp nestled between two peaks and overlooking the 150-foot Short-o-Bacon Falls cascading into the gully below.

"There was nothing in Alaska that could have offered us more. We had found our home," Ledbetter says.

But first, they had to find building materials - wood, hardware, sheet metal - which Ledbetter was able to scavenge from an abandoned nearby mining town.

That was the easy part. Next, he had to pack those materials up the steep, one-mile footpath to their camp.

In fact, everything they owned had to be carried up that trail: groceries; firewood; a 110-pound cast-iron stove. Eventually, Ledbetter enlisted the help of Morgan, a 200-plus-pound St. Bernard whom the couple adopted and trained to pull sleds.

***

It took Ledbetter and Jackie about six months to construct a 15-by-20-foot log cabin - an impressive feat considering they made each cut with a bow saw and hammered each nail by hand.

"I had no chain-saw. I had no electric tools at all," says Ledbetter, who was committed to living off the land.

For five years, the couple lived off-the-grid high in the Coastal Mountains. They collected water from a creek a quarter-mile away, took baths sitting Indian-style in a large salad bowl, and dug an outhouse surrounded by a thicket of lodgepole pines. They tried to garden, but the altitude and short summers made it nearly impossible.

Twice a year, they ventured into Vancouver, 120 miles away, to stock up on dry goods. Otherwise, they raised chickens, fished and occasionally hunted for food.

From October to May, snow was on the ground, enveloping the valley in silence.

"Whenever Morgan barked, I knew to grab my gun," Ledbetter says.

In addition to the detested wolverine and the frequent black-tailed deer, over the years Ledbetter bagged a lynx, a mountain lion and a black bear.

"Strung up, that bear was a good size taller than me," Ledbetter remembers. "We probably ate it for a year. Bear fat makes the best biscuits."

For three years, their lifestyle was sustainable. But the couple had not saved much money prior to arriving in B.C., so eventually they had to go in search of summer work. They found some short-term jobs - one with a wilderness camp and another with the government, doing geological surveys - but options were few.

All the while, their parents wanted them home. Ledbetter's father owned a dry cleaning business and wanted help. Both Ledbetter and Jackie were close with their families, and over those five years, they kept in touch through snail mail, only about once every other month.

"It would have been short-sighted and selfish to stay there forever," Ledbetter says.

In 1976, he and Jackie loaded the VW. Not knowing if or when he'd ever return, Ledbetter wrote the following poem, tacked it to his front door, and was gone.

"Welcome, stranger, to my cabin

If this way you chance to pass

On the door there is no padlock

There is no need to break the glass

You'll find some kindling

Whittled neatly in the box

Build yourself a fire

As for wood, there is lots

Chances are that you are hungry

In the food cans, have a look

Mine are simple eats but plenty

All you have to do is cook

Use the bed if you are sleepy

May your dreams all end happy

Here's to better luck tomorrow,

my unknown friend."

***

In 2018, at age 70, Ledbetter sold the family business which he had taken over from his father 38 years prior.

Ledbetter and Jackie had divorced not long after their return to Tennessee. He had begun to work for his father; she had enrolled in nursing school. And the adjustment had been stressful on their marriage.

In 2016, Ledbetter married Katie, his partner of more than 20 years. Upon his retirement, they planned a 10-week road trip. The goal was to head west in search of his old cabin.

"The road seemed longer when I was young," Ledbetter says, "but I remembered exactly how to get there."

A new logging road had been built, which shortened the steep hike to the cabin, but otherwise, Ledbetter says, almost nothing had changed.

His poem, though weathered with age, still hung on the door. Inside, his possessions were still there, too: his books about backcountry living; his collection of National Geographic magazines; that wood stove he had packed up the trail 45 years earlier.

"It was so, so strange. Like a step back in time," he says.

But improvements had been made to the cabin, too. There was a new set of pots and pans, foam sleeping pads and a fresh stash of toilet paper. Even his food cans were stocked with fresh supplies.

Ledbetter and Katie spent that night at an Airbnb in Lillooet, British Columbia, which he had reserved in case they couldn't find the cabin and also to spare their travel trailer the rugged drive.

That evening, Ledbetter told his hosts the reason for their visit. Their jaws dropped.

"You're the old trapper?!" they exclaimed.

His cabin, he learned, was beloved by the townspeople. Famously known as the "old trapper's cabin," for decades it had been a special gathering place. In fact, someone had once built a sauna there, they told him, though that had burned down.

Other abandoned cabins dappled the Coastal Mountains, but their stories had been forgotten.

"The note I had left on the front door still being there touched my heart more than anything else," Ledbetter says.

And for that note, his hosts told him, "You are a legend."