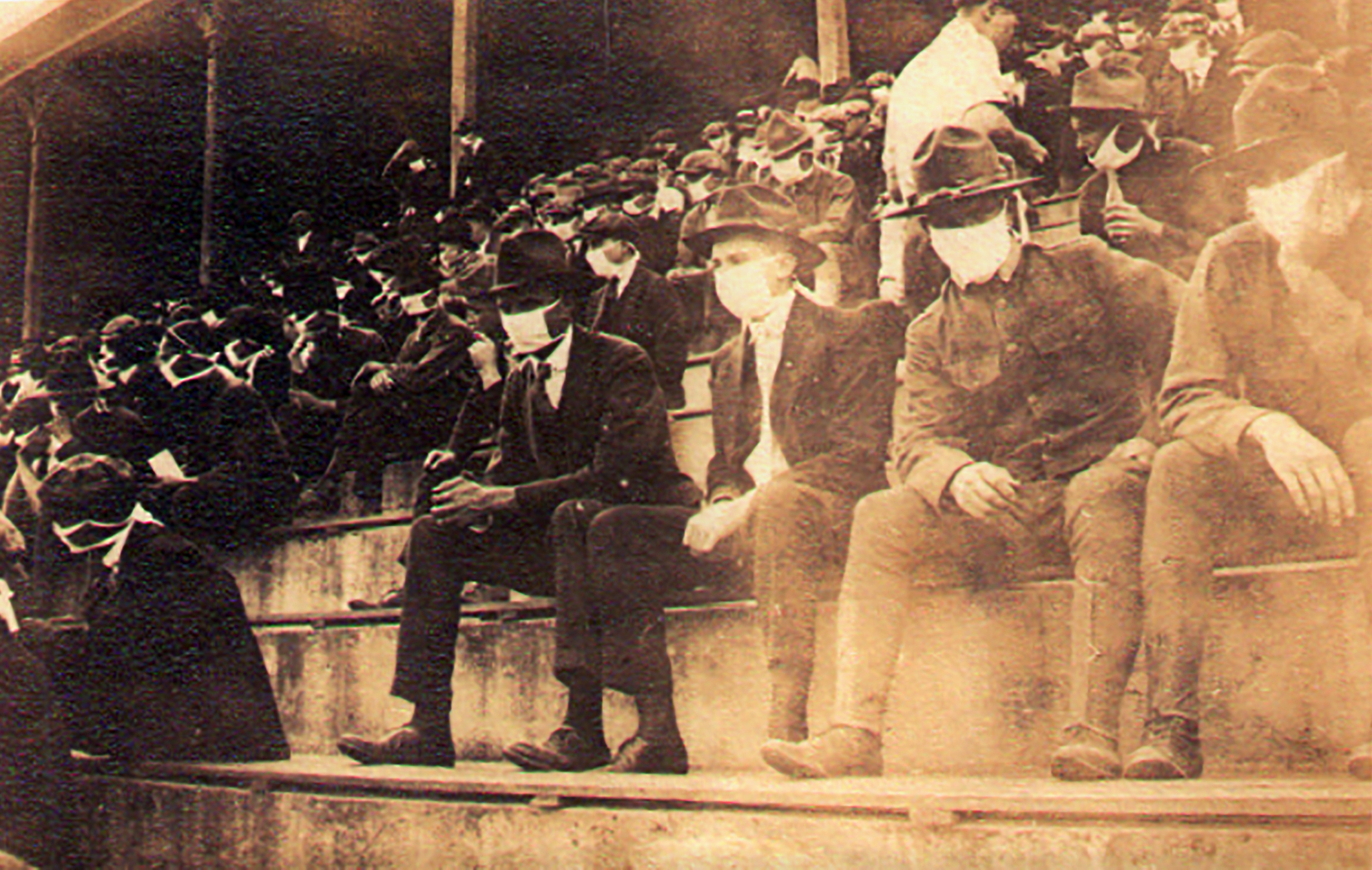

A friend emailed me the photograph a few days ago. It was taken at a 1918 Georgia Tech football game during the Spanish Flu epidemic. Everyone in the stands was wearing a mask. It could have come with the tag line: "The more things change?"

Thanks to the powers that be within the Southeastern Conference, there is every indication that America's most passionate football league intends to do everything within its grasp to not only play that sport this fall, but to have its student-athletes back on campuses on June 8.

Of course, these workouts are being trumpeted as "voluntary," which is probably code for "No one can force you to come, but if you expect to letter this fall, you'll be here on June 8," though no one is likely to own up to that.

To be fair, these aren't full-blown workouts. Social distancing will reportedly still take place. This is more about a return to conditioning in order to be ready for real practices later in the summer.

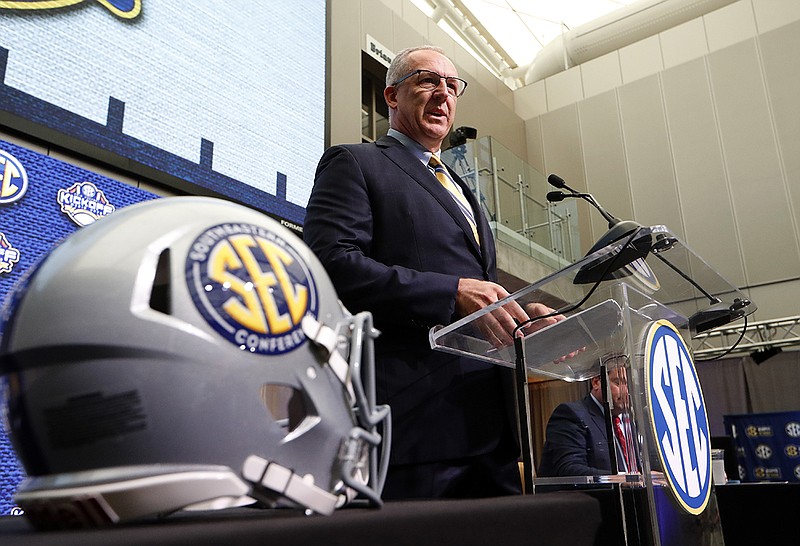

And SEC commissioner Greg Sankey, almost always a voice of reason in difficult times, was probably right to say, as he did on Friday: "Thanks to the blueprint established by our (SEC) Task Force and the dedicated efforts of our universities and their athletics programs, we will be able to provide our student-athletes with far better health and wellness education, medical and psychological care and supervision than they would otherwise receive on their own while off campus or training at public facilities as states continue to reopen."

But let's also be crystal clear that that's not what this is all about. It's about money, or at least the potential loss of more than a billion dollars within the SEC if there is no football this fall.

So all that talk about not having football unless students are back on campus, well, we'll see, because South Carolina is already planning to send its students home around Thanksgiving in hopes of avoiding a dreaded second wave of COVID-19. So would that mean the Gamecocks wouldn't play Clemson on the Saturday after Thanksgiving if campus was already empty until the spring? Would basketball season be placed in similar jeopardy?

Is the sales pitch now that we can take better care of our athletes on campus than if they're confined to their homes, presumably surrounded by family members only?

Certainly we all miss sports these days, and as recent reopenings have shown, a good chunk of the country is ready to somewhat throw caution to the wind in order to return to the lives we once lived. But it is also worth asking if the SEC or any other Power Five league would be considering this if it weren't facing a potentially catastrophic economic future without a football season.

Thomas Carter photo via AP / This undated photo provided by Georgia Tech alumnus Andy McNeil shows a Georgia Tech home game during the 1918 college football season. The photo was taken by student Thomas Carter, who would receive a degree in mechanical engineering. The 102-year-old photo could provide a snapshot of sports once live games resume: Fans packed in a campus stadium in the midst of a pandemic wearing masks with a smidge of social distance between them on concrete seats.

Thomas Carter photo via AP / This undated photo provided by Georgia Tech alumnus Andy McNeil shows a Georgia Tech home game during the 1918 college football season. The photo was taken by student Thomas Carter, who would receive a degree in mechanical engineering. The 102-year-old photo could provide a snapshot of sports once live games resume: Fans packed in a campus stadium in the midst of a pandemic wearing masks with a smidge of social distance between them on concrete seats.What's interesting is to return to that 1918 football season and how former SEC member Georgia Tech chose to handle the Spanish Flu threat that reportedly caused 18 universities to cancel their seasons. Thanks to an excellent article by Tony Barnhart, we know Tech did what most of its major college brethren did not during the autumn of 1918: It played what amounted to a full schedule.

In fact, Golden Tornadoes (Tech's nickname in those days) coach John Heisman played perhaps the fullest slate in the country, scheduling seven games and eventually winning six of them, each of those victories at his team's Grant Field.

So is this a Southern thing, this determination to play college football in even the most hazardous of times?

Not exactly.

Again, Barnhart wrote, no less than Woodrow Wilson, president at the time, believed football improved the country's morale in an era arguably far more terrifying than today, given that the Spanish Flu cut short the lives of more than 675,000 Americans. He even created football teams at various military posts, then had them play college teams.

Wrote Wilson in a letter published a year later: "It would be difficult to overestimate the value of football experience as a part of the soldier's training,"

Today it is hard to overestimate the economic importance of at least attempting to play college football this fall, especially at the Power Five level, where existing television contracts would at least soften the financial strain of playing with far fewer fans in the stands.

But at the risk of sounding like a cynical, (almost) 63-year-old old sports writer, let's at least admit the health of these student-athletes doesn't appear to be as important to the SEC's 14 universities as the declining wealth of its athletic departments.

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @TFPWeeds.