A long time ago, in what is now southwestern West Virginia and Logan County, there were herds of wapiti (WAH-PA-TEE). We are told that is what the Shawnee Indians called them; we call them elk. The wapiti have been gone for a long time, but now they are back.

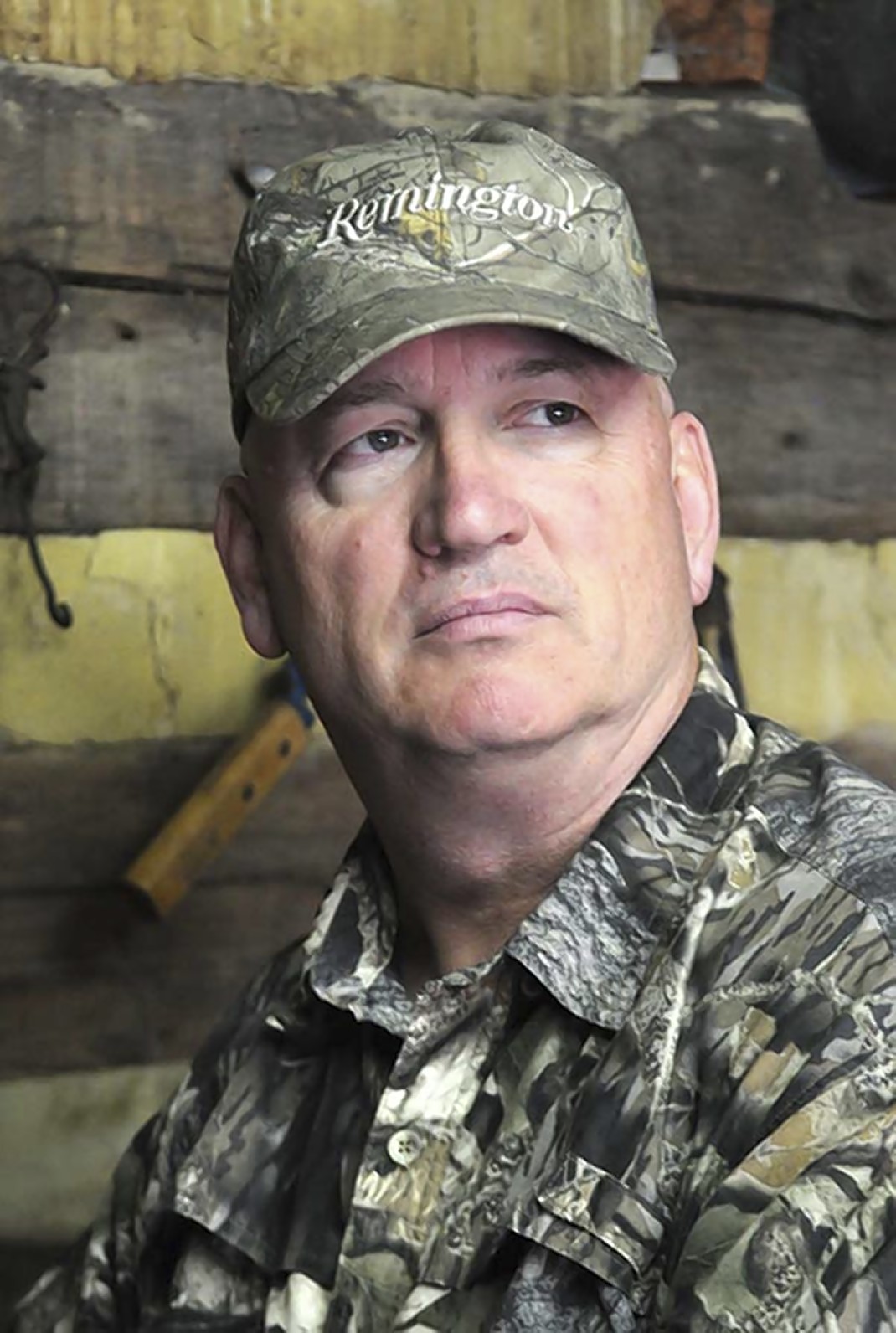

Randy Kelley is a wildlife biologist with the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, and he basically lives with the elk. He has been the leader of the state's elk project since it started in 2015, and he has seen a lot happen.

In 2016, the WVDNR received 24 elk from the Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area in western Kentucky: 12 cows (females) and 12 bulls (males). These elk were released into the Earl Ray Tomblin Wildlife Management Area in Logan County, a WMA covering more than 25,000 acres.

In 2018, WVNDR staff and Arizona wildlife biologists undertook a huge task and captured 60 wild elk (50 cows and 10 bulls), then took them back to the Mountain State. Anyone who has ever dealt with the capture and transportation of large wild animals knows this was no walk in the park. This involved helicopters, guns that fire nets and a lot of wrestling with large animals that know how use their hooves. The Arizona elk had to undergo a lengthy quarantine period due to federal regulations, and some of the elk died due to the stress of the transportation and captivity. Later in 2018, 15 more elk were transported from the Land Between the Lakes.

After the Arizona elk were finally released, the new West Virginia herd seemed to be doing well, but in 2019 the elk received a blow due to an insidious little parasite known as the brain worm. Biologists tell us the brain worm is common among whitetail deer, which have built up a resistance to it. The brain worm eggs are transferred by snails and slugs, which are picked up by the grazing elk. It was a wet year in 2019, and this compounded the snail problem, which transferred more of the brain worm eggs to the elk. The Arizona elk came from a dry and arid region and may have had no exposure to brain worms before; biologists with Kelley on the elk project estimate as much as a third of Arizona elk succumbed to the infestation.

This day I visited Kelley and his fellow biologists, technicians and managers, they were involved in the work of replacing the GPS collars on the elk so they can keep track of them in their daily wandering. Although elk are related to the deer found here, I am told they certainly have different habits and may wander widely - much more so than their smaller cousins - so the collars are vital to keeping up with the elk's whereabouts. Some of the collars from the original stocked elk needed replacing, and there are young elk that have been born here, so they need collars, too.

The elk are captured by baiting them in with alfalfa hay, corn and other elk goodies, and a biologist hides in a blind built for this purpose. A tranquilizer dart is fired, and the elk is soon on the ground so the biologists can do their work quickly and replace the collar.

I ride to the blind with Kelley and wildlife technician Jake Wimmer. Randy loads a very impressive looking CO2-powered dart gun, puts on scent-proof camo as a bow hunter would, then disappears into the blind. Wimmer puts out more feed, and then we are back in the truck, headed to the staging area to wait with the rest of the crew about a mile away.

"It's a waiting game, just like hunting," Jake tells me. "All we can do is sit and be patient and hope the elk come in. They may, or they may not."

The afternoon sun is warm, and after a long winter we are all enjoying it. The talk is interesting to me, as always in a group of wildlife professionals who have good stories to tell. Someone produces a new bass rod-and-reel and starts casting up and down the muddy road to try it out. The sun feels great, and life is good.

The radio crackles, and I can hear the excitement in Kelley's voice: "We've got an elk down, get over here!"

I jump in a truck so I won't get left behind, and we are off. A few minutes later I am looking at a beautiful young bull elk, and the DNR guys and one lady leap into action. It is obvious they know their job, and they want this to go quickly and get the elk back on his feet. I try to stay out of the way and take pictures while data is gathered, blood samples are taken and a collar is placed on the young bull. Randy injects a drug to wake the bull up, and I am told to get out of the way.

In a few minutes, the elk is on his feet, and although a little groggy, starts to walk away. He stops about 20 yards out and gives us the classic look, then wanders off into the brush. I watch him go and wish him well. I hope he lives to grow a monstrous 7-by-7 rack and sire many calves for the herd.

It will be a while, but within a few years there will be some lucky hunters who get to pursue these elk in the West Virginia mountains. That is good and I wish them luck, but I also want the elk to grow and prosper here so that my children and grandchildren can hear the bugle of the wapiti in these mountains once again.

"The Trail Less Traveled" is written by Larry Case, who lives in Fayette County, W.Va. You can write to him at larryocase3@gmail.com.