The answers by Chattanooga City Council and Hamilton County Commission members last week to a Times Free Press question as to whether they had taken the COVID-19 vaccine paint, not surprisingly, a picture of the wider community and country.

The answers ranged from "follow the science" to, in essence, mind your own business.

What each individual chose to do also varied across gender, racial and political lines. Their answers proved who chooses to get vaccinated is not as cut and dried as the national media pretends.

Republicans on the two bodies - the city council is officially nonpartisan - both advocated the vaccine and were hesitant or chose not to respond. Democrats were both for it and were skeptical about it.

One commission member - Randy Fairbanks - and four city council members - Demetrus Coonrod, Raquetta Dotley, Darrin Ledford and Ken Smith - did not respond.

Individual members could have a number of reasons why they didn't respond. Among them: They may not have seen the question, saw it and chose to ignore it, or saw it and were afraid their answer might not have sat well with their constituents.

But their responses made us ponder. As elected officials in the midst of a once-in-a-century pandemic, is it incumbent upon them to reveal their thinking when it comes to vaccinations?

We think if they saw the question, they owe it to their constituents to say something.

Commissioner Greg Martin and City Councilman Chip Henderson, for instance, did not share their vaccination status. But they did respond and say the choice was one individuals should make with their medical professional or health care provider.

Most medical professionals we know are fully behind the vaccines, but if it helps individuals to have the blessings of their doctors, we are fully supportive of those conversations.

Commissioner Katherlyn Geter called the vaccine one of "the tools in the tool box" against COVID-19, and she said that after contracting the virus both before and after having the shot this spring. Yet, she said "it's not for me to persuade a person to get vaccinated."

Commissioner Chairman Chip Baker, who was trained as a biologist and spent 20 years in the health care field, said he has "a penchant to follow the science" and reads science and medical journals. So while what he knew and learned influenced his decision to get vaccinated, he also talked to his physician. But he also called it "a personal choice."

Two members of the governmental bodies - Commissioner Tim Boyd and Councilwoman Carol Berz - saw things a little differently and called getting the vaccine a moral obligation. Boyd said it shouldn't be a "partisan issue," while Berz similarly said it shouldn't be a "political issue." Both mentioned the importance of protecting others from the virus, which is how we likewise see it.

Both Hamilton County Mayor Jim Coppinger and Chattanooga Mayor Tim Kelly are vaccinated and are vaccine proponents. Kelly, like Geter, contracted a breakthrough case of the virus - the mayor's last month - after having been vaccinated.

Perhaps to avoid such breakthrough cases, Coppinger and Commissioner David Sharpe said they're anxious for their vaccine booster, which currently has only been authorized for certain immunocompromised people. However, the Biden administration is expected to lay out a booster vaccine strategy for all vaccinated Americans later this month.

The two most intriguing responses came from Commissioner Sabrena Smedley and Councilman Anthony Byrd, both of whom either haven't gotten a vaccine in the case of Smedley, a white Republican, or have recently gotten a first shot in the case of Byrd, who is Black.

Smedley said she is "not wanting to take medicine" and "just jump on a vaccine or something." But she said that's not to say there might not come a time when she would take it.

Byrd, meanwhile, referenced his hesitation on a shameful U.S. Public Health Service program that ended almost 50 years ago in which Black men with and without diseases who lived in Macon County, Ala., were treated for "tired blood," a common term used at the time for a variety of ailments. In truth, none were treated properly, and many died unnecessarily or were left seriously ill.

"It's just the history of government and how things have been done to African Americans over the years," said the councilman, who is one of four Blacks on the nine-member council in a city with a population that is slightly more than 29% Black.

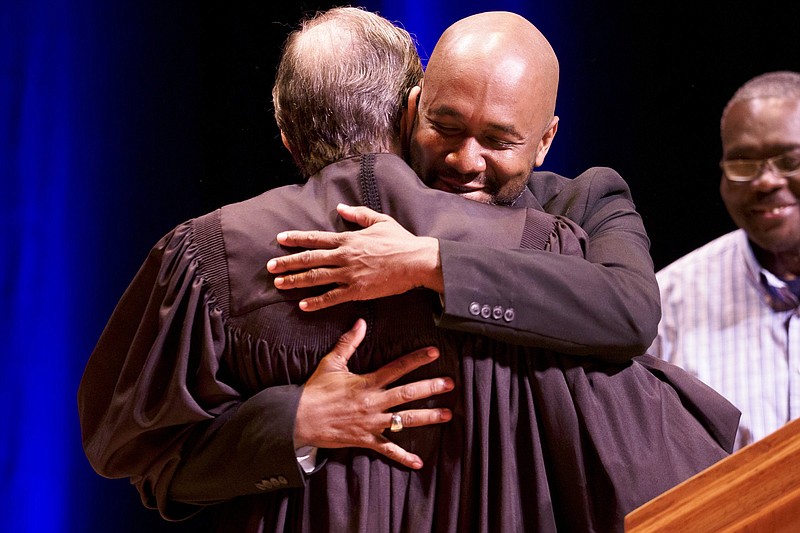

Nevertheless, the full approval of one vaccine by the Food and Drug Administration, the death of two friends from the virus and his status as a father of three children changed Byrd's mind.

So, is Chattanooga some redneck Southern outlier of a city in which just irresponsible Republicans are vaccination holdouts, as some writers would have you believe? As the Hamilton County Commission and Chattanooga City Council prove, that is hardly the case.