Chattanooga loved Mayor Robert Kirk Walker's plan for an "urban oasis" across from the federal courthouse. A combination of private and public funding, coordinated by Walker and Scott Probasco, had enabled the city to purchase the property. Jim Franklin's vision of a park based on "human needs" had been unanimously selected by the oversight board. Now it was time for action.

On May 30, 1976, Jim Franklin returned to Chattanooga after spending several days lecturing at the Recreation Resource Planning and Design Institute, coordinated by Michigan State and attended by representatives from across the United States, each interested in "innovative solutions" to recreational planning. Franklin's previous experience in the public sector, including the development of design plans for Fall Creek Falls State Park and Red Clay Council Grounds among other projects, had made him well-known in recreational design circles. His multi-lecture series at the institute had cemented his national reputation. Immediately upon his return, the architect set to work.

As he talked about the center-city park, Franklin noted "a constantly accelerating trend toward developing recreational projects." Citing an increase in leisure time as society had moved toward a 40-hour work week that seldom included Saturday jobs and a trend to move into cities with limited access to open lands, Franklin believed that public recreational projects had increased in importance.

So how would his design answer those needs for residents? His plan focused on a "green oasis which can accommodate large numbers of people" and a site where plant materials can "survive in a sunbaked environment," stressing that the real client is not the city but the person who is going to use the park. His bottom line for the design was simple -- "recreational planning as a response to human need."

Two weeks later, the front page of the Chattanooga Times proclaimed the "Downtown Park Now Miller Park, Honoring Burkett Miller's Parents." Former Mayor Walker announced that the park board had passed a resolution to name the park as a "much deserved tribute to a man whose vision and personal efforts were instrumental in bringing into being what promises to be a beautiful and much-needed addition to our downtown area. Board member Probasco was "particularly enthusiastic, calling the idea ... super and most appropriate."

Burkett Miller, a Chattanooga attorney and businessman, had generously donated properties needed for the project after spending years promoting the idea of a downtown park while a member of the executive committee of the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce.

"I continued to press the idea of a park ...," he said, "but no action resulted until Robert Kirk Walker became mayor and Joe Davenport became chairman of the downtown development committee."

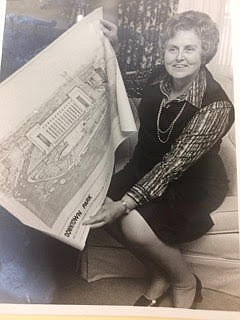

By September 1976, the vision had expanded, and Joy Walker, park program coordinator, was "determined that the city's new Miller Park is going to fill with citizens attracted by a scenic site and by the best entertainment Chattanooga has to offer." Walker had interviewed more than 50 individuals, soliciting ideas about programming to supplement the knowledge she had gained through her own experience as a civic volunteer.

Additionally, during her husband's term as Chattanooga mayor, she had championed public art exhibits and other community programming at City Hall, working with citizens to determine areas of interest and need. That experience and her "people-oriented" personality allowed her to envision lunchtime public performances at the park, designed for downtown workers.

With the park slated to open in three months, she had already begun scheduling school music groups, local performers, art exhibits, and craft and garden shows while learning more about the technical skills and equipment needed for public performances.

"The word picture that hits me when thinking about the park is one used by one of the project architects; it is designed as Chattanooga's living room," she said.

While Miller Park had not been completed by Dedication Day in December 1976, Scott Probasco proclaimed it a "jewel, a beauty spot in a downtown which is becoming more beautiful all the time." More than 150 people braved the threat of a winter storm to celebrate the new park and applaud the activation of the fountains and waterfall that served as the park's centerpiece.

Burkett Miller, hospitalized in Miami, was unable to attend but sent a telegram, assuring attendees that "nothing can ever deprive me of the heartfelt thanks of having been permitted to see the realization of a dream of more than a quarter of a century ... ."

Linda Moss Mines, the Chattanooga- Hamilton County historian, serves on the Veterans Memorial Park board and is a Chattanooga parks advocate. Go to visit Chattahistoricalassoc.org.for more local history information.