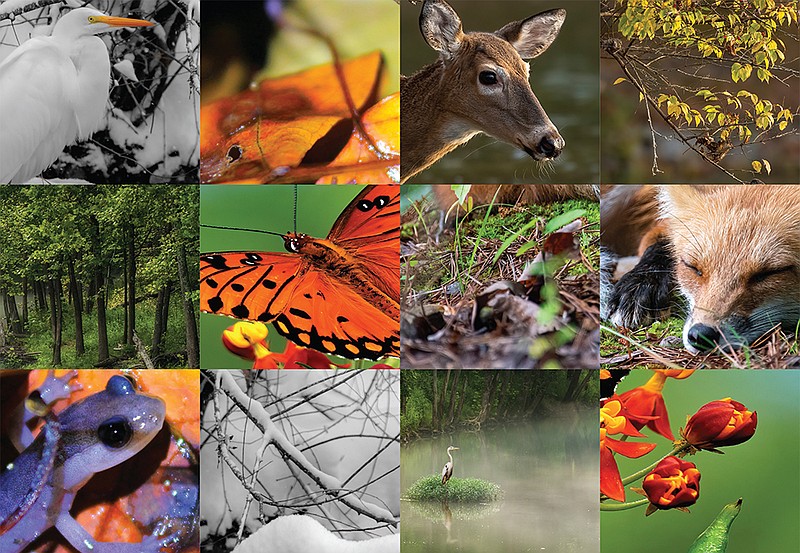

Each year, the Tennessee Wildlife Federation hosts a photography contest, inviting amateurs and professionals alike to enter their best images of state wildlife and natural areas.

And subjects abound, from the Western swamps to the Eastern mountains.

"Tennessee is the most biologically diverse inland state because of that topography," says Kendall McCarter, chief development officer for the nonprofit. "It's spectacular the quality of photos we get -- some of the best in the world."

Of the thousands of photos submitted this year, 17 were selected for prizes, which included Patagonia gear and gift cards, federation swag and a spotlight in its 2023 calendar.

The calendar becomes a gift to any donor who gives $60 or more between Nov. 1 and Dec. 31.

The contest itself helps the federation generate a library of local photography. Those who enter give the federation permission to use their images (with credit) on its website and in other promotional materials -- thus saving tens of thousands of dollars in licensing fees, says McCarter.

That money can then be put toward more pressing matters such as the federation's new anti-litter initiative. In August, it announced a statewide collaborative effort called Tennessee Cleaner Landscapes for the Economy, Agriculture and Nature (CLEAN), to address litter pollution on every level.

Here are a few winning photos to be featured in the 2023 calendar, plus interesting trivia to help further illustrate why the work of the Tennessee Wildlife Federation matters so much.

Grand Prize Winner

"Passing Fritillary" by David Liles

Location: Knoxville

This Gulf fritillary butterfly is the first insect to make the calendar's cover, McCarter says.

"Last year we had a majestic bull elk on the cover, but this year, we wanted to draw more attention to [pollinators]," he says.

In the U.S., there are 30 species of fritillary butterflies, named for the checkered pattern displayed on their wings. "Fritillary" comes from the Latin word "fritilus," which means chessboard or dice box. Because of their distinct spots -- often orange and black -- they are sometimes mistaken for the monarch butterfly. To distinguish between the two, remember that a monarch has two rows of white spots at the edges of its wings.

Like most butterfly species, a fritillary caterpillar is very selective about what it eats. Unlike the monarch, whose caterpillar feeds on milkweed, the fritillary prefers violets. According to the U.S. Forest Service website, "without violets, there would be no fritillaries."

People's Choice Winner

"Sweet Dreams" by Christopher Barger

Location: Roane County

The red fox is found statewide, though rarely seen. And while it is not a pollinator like the butterfly, the small, wild canine does help support forest flora in important ways. First, foxes love to eat persimmons, a native, fleshy fruit with hard-shelled seeds. Studies suggest that these seeds have a higher rate of germination after passing through a mammal's digestive tract. Moreover, the omnivorous red fox helps disperse a variety of other seeds through its scat -- blackberries and mulberries, for example.

Fox, about the size of an adult housecat, are mostly active at night, which is why they're so elusive. Still, it's an iconic species, so it's no surprise the image was selected as this year's People's Choice, a segment of the contest that invites the public to visit Tennessee Wildlife Federation website and vote for their favorite photograph.

Landscape Winner

"Morning Mist" by Brenda Walker

Location: Little West Fork Creek in Clarksville

Just south of Fort Campbell at the Kentucky-Tennessee stateline, Piney Fork and Noah's Spring Branch come together to form Little West Fork Creek. One accessible way to enjoy a scenic stretch of the water is via the Clarksville Greenway, which transforms an abandoned railway into a paved walking path. The 9-mile greenway meanders along the banks of the Little West Fork and Red creeks, showcasing a variety of landscapes, from bluffs to bridges, to forests and open vistas.

Part of the contest's purpose is to show people beautiful places they can explore in Tennessee, says McCarter, but it is also to promote low-impact ways to enjoy those places.

"Photography is such a great way to do that," he says.

Monthly Winner

"Great Egret in Snowy Creek" by Timothy Lloyd

Location: Hendersonville

The symbol of the National Audubon Society, the great egret is the largest of white herons in Tennessee, but it can still be tricky to differentiate among such similar species as the snowy or cattle egret.

A few tips to remember: The great egret has a yellow-orange bill whereas the snowy has a black bill. And while both the great and the snowy forage near water, the cattle egret (which is shorter and stockier than both) is more often found foraging in grassy fields and farmlands.

The three species are more common in West Tennessee generally from spring to early fall, but they can be found statewide. And occasionally, according to Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, a few great egrets spend their winter in the state -- which may have been the case of the egret featured in this winning photo.

Monthly Winner

"Easy Does It" by Scott Russom

Location: Radnor Lake in Nashville

White-tail deer are famously skittish, but they're also surprisingly athletic.

An adult white-tail can sprint up to 35 miles per hour, and, from a standing position, they can jump 7 feet or higher. And they're excellent swimmers. In fact, white-tail deer have been known to clock speeds up to 15 miles per hour in the water -- more than twice as fast as Olympic Gold Medalist Michael Phelps, whose maximum swim speed is about 6 miles per hour.

Monthly Winner

"Loving the Leaf Litter" by Lauren Lyon

Location: Unicoi County

The Northern gray-cheeked salamander, pictured here, is a high-elevation-loving amphibian, with Tennessee populations found in Great Smoky Mountain National Park and along the Western slopes of the rugged Blue Ridge Mountains.

The Southeastern U.S. is known to have the greatest diversity of salamanders in the world, but a massive number are being lost each year. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed around half of all the world's salamander species as threatened due mostly to human activity.

Here are a few easy ways to help protect their populations: When visiting forested, natural areas, avoid wearing DEET bug sprays or sunscreens, which are lethal to young salamanders. Instead opt for light long-sleeve shirts, hats and sunglasses for protection. Moreover, avoid handling them altogether. Salamanders have very absorbent skin, and even the natural oils on a person's hand can be harmful. And finally, never move logs, leaf litter or rocks, especially near streams, as they serve as critical shelter for the vulnerable animals.

Get the calendar at tnwf.org.