Raised in working-class East Chattanooga, Eric Scealf knew he looked like a redneck. But when he heard the Clash and the Ramones, he knew he was a punk rocker.

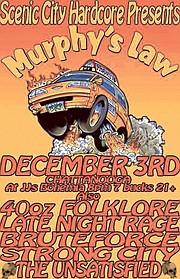

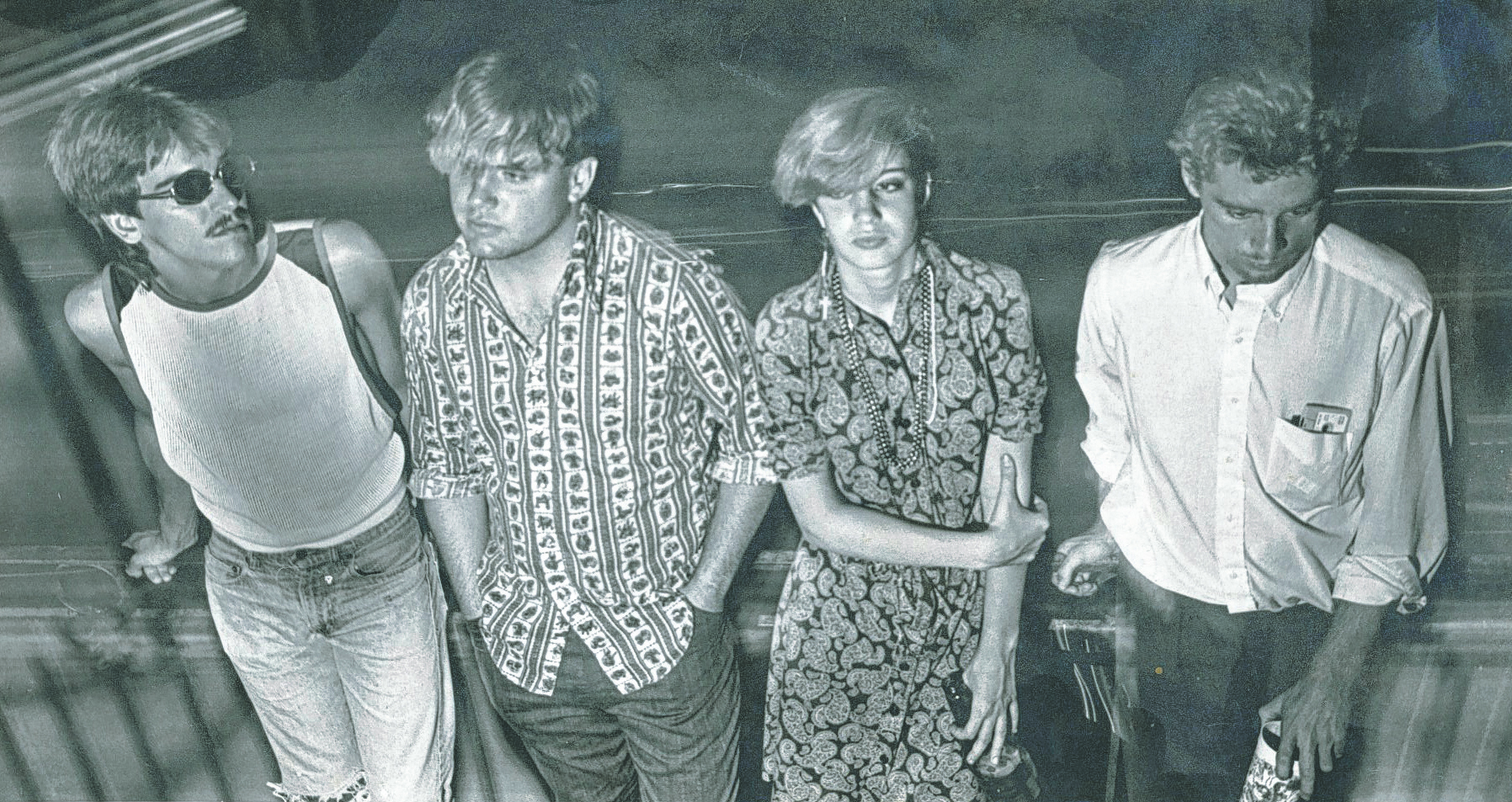

He formed The Unsatisfied in 1986, which would one day play New York's legendary CBGB and open for the Ramones and Iggy Pop. But before Scealf met those rock gods, he earned pocket money mopping post-concert vomit off the floors of downtown bars, the primary venues for punk rock.

His family was scandalized that he performed shirtless and wearing eyeliner. After verifying that he was heterosexual, his politically conservative family, who spoke in tongues at church, figured he might be Satan.

"I looked through the Book of Revelations and thought, 'Well, maybe I am the Devil, but at least I think for myself,'" Scealf says. "I got my politics from (Clash guitarist/vocalist) Joe Strummer, not Ronald Reagan."

Punk rock erupted in mid-'70s in Britain and America. New York's Ramones released their first album 40 years ago this month. The self-titled LP helped cement the sound of punk rock. But punk's true roots go back to the 1969 releases of "Kick Out the Jams" by MC5 and the self-titled debut from the Stooges, two bands from industrial cities in Michigan, MC5 from Detroit, Stooges from Ann Arbor.

Punk was fueled in an era much like the one millennials currently face. A severe recession sparked angry debates about income inequality. America had suffered through the long, unpopular Vietnam War. Terrorism seemed omnipresent with plane hijackings, kidnappings and bombings by Black September in the Middle East, Italy's Red Brigades and Germany's Baader-Meinhof gang.

Disco, mainstream rock and country music were too manufactured and vapid to reflect such strange times. Punk's emotional intensity, super-fast beats and scathing lyrics felt fresh and compelling. While some music stars of the times had coiffed hair, rhinestones, polyester and lipstick, punks like the Ramones flaunted shaggy hair, battered leather jackets and torn jeans from their own closets.

But in Chattanooga, far from the mean streets of New York, punks found few places where they could play.

Like other pioneering Chattanooga punk bands, The Unsatisfied played in a Glass Street pool hall called Hollywood's. There was no social media, so they drew fliers and plastered them on fences, walls and telephone poles. Chattanooga's pioneering punk bands drew suburban youths downtown long before the Tennessee Aquarium spawned urban revival. When bands couldn't afford to rent a room, they asked the city if they could rent a park gazebo and, Scealf recalls, played for youthful rebels, wild dogs and winos.

"Downtown was a cesspool and deserted at night," says Scealf, who today is an entrepreneur with two grown daughters yet still as wiry and fit as when he was a somersaulting across Hollywood's stage back in the day.

"At Hollywood's, I fought bikers who pulled knives on us, skinheads who disrespected blacks. I jumped into mosh pits to break up fights and cut my skin on broken glass all over the stage. But we also drew Signal Mountain rich kids. McCallie's kids would gel their hair into mohawks for concerts then combed it down for school."

Disclosure CTFP policy

Normally, the Chattanooga Times Free Press does not interview current employees as sources for stories. Because Jody Park, a member of the newspaper’s Web team, had a key role as a musician in the local 1980s punk rock scene, editors made an exception in order to include his memories in this article.

Jody Park was a member of Hank, a trailblazing punk band. He plays in The Finks now; his thick, brown hair is intact and he still lugs his amps and equipment onstage. "That proves how much I love the music," he jokes.

Park, who now works for the Times Free Press on the Web team, helped write the music for songs including "K-Mart Town," about a city that took pride in churches, malls and catfish restaurants rather than culture. When talking to people who were part of the local punk scene decades again, Park's name comes up over and over.

"We would have played anywhere - rec centers, suburbia," says Park, who recalls a punk concert in a North Chattanooga adult movie theater. "Most venues thought we were too young. Our drummer and guitarist were in high school. Going downtown had a guerrilla-arts feeling that was more exciting and fun."

For one show, Hank played in an abandoned building off Highway 58.

"We brought our own gas generator and extension cords to plug in our instruments," Park says. "We lit candles to illuminate the area. But when the audience danced, they kept accidentally kicking plugs out. Then we saw a house about a football field's distance away from us."

Hank linked all of its extension cords together into a snake that stretched from their crumbling ruin to the house. The singer knocked on the door and asked to use the home's electricity. The parents were gone, so the teenagers there happily agreed.

Another night, Hank played the Go Go, a gay downtown dance club where the band shared a dressing room that belonged to gracious drag queens.

"The audience was very engaged, and our lead singer got carried away," Park says. "He jumped up to grab a lighting fixture and it crashed out of the ceiling. He grabbed a bottle of Jack (Daniels), drank it, then ran into the night."

Hank also played a Students Staying Straight dance, a high school anti-booze and drugs event.

Finding its place

Being a young activist in the '80s after the turbulent, inspiring 1970s was like arriving at a party to find nothing but food crumbs and trampled confetti. But a young romantic who's musically talented and naive might believe a band has the power to make the world better.

"Punk seemed more than music; it was a movement uniting the 99 percent with women's rights and black power activists in the South," Scealf recalls. "I hired a girl guitar player and a girl bass player. Punk women could hold their own with the macho guitar slingers."

The loud crash and drive of punk never matched the popularity of thump-thump-thump of disco. The Ramones never had an album inch higher than No. 77 on Billboard's chart. But punk always punched higher than its weight class when it came to creativity.

Wings, Elton John, Michael Jackson and Olivia Newton-John ruled the late '70s Billboard charts with sweet, sunny songs. Now consider the Dead Kennedy's 1980 song "Kill the Poor," which satirized politicians bashing the underclass. The lyrics urge ending poverty by bombing slums: "The sun beams down on a brand-new day, No more welfare tax to pay, Unsightly slums gone in flashing light, Jobless millions whisked away All systems go to kill the poor tonight."

Punk's Jonathan Swift-ian wit attracted Chattanooga fans who describe themselves as dreamers drawn to intellectual fireworks. Punk's inclusiveness meant a rocker didn't have to be too skilled on an instrument.

Gary Hasty, now the event coordinator for the Downtown Development Authority in Kennesaw, Ga., was a Dalton punk as a high schooler in the early '80s.

"(Chattanooga's) Baby Fae & The Heartless Baboons let me play because they liked my look - green dreadlocks, piercings - and I had $100 for a bass," laughs Hasty. "I maintained an A average in school while I played."

Blazing trails

Chattanooga Crye-Leike Realtor Scott Louisell has his first Clash album, "London Calling," purchased on New Year's Eve 1980, framed on the wall of his home. He secretly heard the Ramones for the first time as a pre-teen in summer camp.

"The powers that be banned electronic equipment for the purpose of getting back to nature - in retrospect, a wise idea," he explains.

"At the time, no one liked it," Louisell says. "The lone exception was a Jewish kid permitted to keep a tape player to prepare for his upcoming bar mitzvah. He smuggled in Ramones cassettes."

Louisell says he knew the Ramones and the Clash would be enduring icons the first time he heard them. Their utter scorn of the status quo, their comfort in their own skin and the Clash's mix of idealism, compassion and realism captivated him forever.

There were local record stores where punk fans would meet and exchange ideas - Kats Records, Oz, Melonhead Music, Chad's. By the mid-'80s, a new club called Nucleus welcomed punks at Fourth Avenue and Main Street. Scealf got a job there. He duct-taped windows before seminal punk band Black Flag played there in case their noise shattered glass. He helped Flea from Red Hot Chili Peppers unload the band's equipment from its bus.

In 1984, Randy Black hosted the city's first punk/alternative radio show, "Aftershock," which was sponsored by Nucleus.

"I interviewed local bands that played there including The Value, Hank, Red M&Ms, The Abstracts, The Unsatisfied, Musical Moose," Black says.

The show, which aired on WDBX-AM radio "was the top in its time slot when FM was king," says Black.

Shaking Ray Levi Society was drawing visitors downtown with art shows, including one starring outsider artist the Rev. Howard Finster, who won national fame as the artist who created album covers for R.E.M. ("Reckoning") and Talking Heads ("Little Creatures"). Finster married Hasty and his wife.

"We had another wedding in Las Vegas performed by an Elvis impersonator to make sure our marriage was legit," Hasty adds.

Hasty now manages the ChattaPunk Facebook page for veteran and rookie rockers. He booked The Unsatisfied for an April beer festival in Kennesaw. Burnt Hickory Beer, a brewery supplying the event, was founded by Scott Hedeen, frontman for punk band Red Weasel.

"The founder funded the brewery by selling part of his record collection," Hasty says.

The future

Adam Foster booked his first punk rock show at age 14 in 2000 in his grandma's East Ridge garage; 30 kids attended the daytime show - then the police came and arrested Foster's grandmother.

"She refused to sign paperwork saying she was running an unruly household," Foster says. "She told the cops she wasn't violating any noise ordinance. No one was drinking, smoking or taking drugs. Neighbors complained because the kids looked weird. The East Ridge cops turned her over to the Hamilton County police."

How did they respond?

"They laughed," Foster says, also laughing, "and let Grandma go."

Officials at Notre Dame High School warned Foster's mom punk rock was anti-authority. But she still drove him to gigs until he got his driver's license. His local punk idol, The Jack Palance Band, inspired him to stay in music. He now earns a living booking bands and working as a unionized stagehand.

One of the bands Foster promotes is Bear Comes Home, which got its name from a storybook. The band's drummer Philip Amos, 18, began playing in punk bands at 14. His mother also drove him to gigs in bars.

"Legally, a minor can play a gig where liquor is served but not where there is smoking," Amos explains.

The band painted an angry bear on the cover of each copy of its debut CD. One band member used his own blood as pigment.

"When I was in eighth grade I heard the Misfits, the Clash, Sex Pistols, Ramones in skateboarding films; I was hooked from the start," says Amos. "Hardcore punk is the blood in my veins. It is music of aggression, understanding and forward thinking."

Amos, who works his gigs around his construction job, sounds as idealistic as old-school punks when he extols the genre's belief in racial equality and social justice. He describes himself as Christian "but not a bigot, racist or homophobe."

Chattanooga still has an annual punk-rock event called Do Ya Hear We? Punk Fest. Ziggy's, JJ's and Sluggo's in Chattanooga and Cloud Springs Deli in Ringgold, Ga. welcome punk bands, but Amos feels some venues are reluctant to promote a genre as provocative as punk.

"Turnout was decent at my last gig only because lots of out-of-town friends traveled to see us," Amos says. "Older people in Chattanooga punk can be jaded and think younger people have no idea what punk is."

Scealf worries that some punks now are snobby toward bands who don't sport enough piercings and hair gel.

"Style snobbery is the absolute contradiction of the punk spirit," fumes Scealf. "I hated disco but I really hate this American Idol-type obsession with making musicians fit a mold. Punk is inclusive. Millennials who are abused by the economy should feel a connection with punk. Punk was empowering. That music made me the star of my own life."

Musician Brien Teff was a skate kid like Amos and discovered punk via Thrasher magazine profiles of the Ramones. He's a daddy now and wants young rockers like Amos to enjoy the empathy he found behind punk rock's roar.

"The music and lifestyle is extremely relevant today. Punk was started by kids for kids creating something that was theirs. It still is," Teff says. "I've made lasting friendships in punk with some of the best people I've known. Some of us hated our families for various reasons, so we made families of our own."

Punk helped Scealf make peace with his own highly religious family. His dad was a gifted amateur musician until he was injured in a horrific car accident. Shortly before his dad died, he got to see The Unsatisfied play for a crowd of 1,000 at the University of Tennessee. Punkers in the mosh pit picked up his wheelchair-bound father and gently passed him in his chair over their heads, placing him onstage next to his son.

Scealf now is making a record in Nashville in the studio where Elvis Presley recorded the last song of his life, "Way on Down." His engineer is Joe Funderburk, Merle Haggard's longtime engineer.

"I didn't save the world, although I thought it was up to me to do that when I was young," Scealf says. "But maybe I changed a little bit of it. And Jesus hasn't returned as the messiah. But maybe he never left."

Contact Lynda Edwards at ledwards@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6391.