The Rev. Steve Caudle is trying to save lives. Some days, that means signing people up for a COVID-19 vaccine appointment. Sundays, that means preaching about getting your shot.

"Ignorance enslaves us. My people perish due to a lack of knowledge, the Bible says. So, if it's truth and it's going to help people, it needs to come from that sacred desk," said Caudle, senior pastor of Greater Second Missionary Baptist Church, while gesturing toward the dark wooden lectern of the sanctuary.

"I don't care what people's personal opinions are. I don't care about their political persuasion. I could care less. If it's the truth, if it's going to save lives, it should be preached from that pulpit."

Local campaigns to address vaccine hesitancy are tapping leaders like Caudle to raise awareness and make sure people who want a shot get one. Hamilton County's efforts to boost vaccination rates among Black residents is a potential success story in progress as rates have risen somewhat in recent weeks.

The pandemic widened fissures in American society over the past year, from debates over mask regulations to vaccine safety. It also deepened divides among American houses of worship.

Across the country, some church leaders publicly defied gathering restrictions and held services. Some houses of worship, including one in Chattanooga, sued their local governments over virus-related restrictions on gathering

Research and polling now suggest that white evangelicals are among the most likely to refuse the COVID-19 vaccine, along with non-health care essential workers and rural residents.

In nearly four decades of church ministry, Caudle said he has never seen anything like the past year. The political division. The misinformation. The outright refusal from pastors to follow safety measures Caudle believes save lives.

"You have to be surprised: A nation like this that has all of its advantages, technological advantages, I thought governmental advantages, and just 'good, reasonable, Christian people' would behave in a certain way other than what we have witnessed," Caudle said.

OUTREACH CAMPAIGN

Black residents make up about 19% of Hamilton County's population and, as of this week, accounted for 12.4% of the doses administered, according to data from the Tennessee Department of Health.

However, since March 27, when vaccines became available to all county residents age 16 and older, the number of Black residents who received a shot increased by 51.4%, a larger increase than the 43% jump among white residents during that same time period, according to the state department of health.

Since March, health officials and community leaders have worked on the "Get Vaccinated Chattanooga" campaign, which features culturally relatable and understandable educational materials, social media ads, billboards and recognizable community members sharing their vaccination stories. The campaign, which involves clergy, is focused on particularly vulnerable populations, including African Americans, Latinos, homeless, children, people with disabilities, older adults and people experiencing homelessness.

The Hamilton County Health Department built relationships with more than 70 Black churches to address hesitancy and help schedule vaccine appointments, said Dr. Valerie Boaz, a former health officer for the department.

JaMichael Jordan, pastor of The Village Church, said he got vaccinated to protect his two sons, both of whom are too young to receive a dose. Jordan said he leads by example and can be a familiar and trusted face for those who are hesitant. The pastor is featured on a billboard promoting vaccine awareness.

Pop-up vaccine events in Hamilton County

The Hamilton County Health Department is making available doses of the Pfizer vaccine during pop-up events at the following locations:The Bethlehem Center, 200 West 38th St, Chattanooga, TN 3741011 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. on Saturdays — May 29 and June 19Super Carniceria Loa #6, 400A Chickamauga Rd Chattanooga, TN 3742111 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Friday, June 4Birchwood Clinic, 5625 Highway 60, Birchwood TN, 373089 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Wednesdays — May 19, 26 and June 9, 16

People may be concerned with uncertainty over the long-term effects of the vaccine, Jordan said, but his congregation knows the short-term effects of the virus: People in his congregation or people connected to his congregation have died from the coronavirus. Across the country, communities of color have been hit disproportionately by infections and deaths from the virus.

"If we're going to see some sense of normal, we can't sit still and continue to let this virus have its way with us," Jordan said. "We have to seek the help from God, the wisdom of our scientists and the people who are creating vaccinations and listen to all information."

The locations of vaccination events play a key role in reducing hesitancy, too, Caudle said. Places like Enterprise South Nature Park or the Tennessee Riverpark, where the county health department held daily mass vaccination sites, are not familiar to some people. But when events are held at Howard High School or Brainerd High School, for example, people feel comfortable, he said.

"It's a community that we are familiar with," Caudle said. "This is how you do it. That's how you reach a community like ours. You go to those landmarks and those institutions that many of them attended and graduated from."

Becky Barnes, administrator for the health department, said locations of vaccine events, especially those aimed at addressing vaccine hesitant groups, are determined based on accessibility for community members. In some instances, the health department will send strike teams to communities to provide doses, Barnes said.

Despite their faith tradition supporting vaccines, white evangelicals are among the most likely religious Americans to say they will not receive a COVID-19 vaccine, with between 40 and 45% reporting they will avoid the shot, according to polls from the Pew Research Center and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Another survey, from the Kaiser Family Foundation, found that nearly 30% of white evangelicals said they would "definitely not" take the vaccine.

A study published December 2020 in the journal Sociological Research for a Dynamic World found that religious and political belief in an individualist and nationalist Christian ideology was the strongest predictor for anti-vaccine beliefs among Americans, more than any individual religious or political identity on its own.

In general, mistrust drives vaccine hesitancy, said Robert Bednarczyk, assistant professor of global health at Emory University.

In Black communities, that can be mistrust of the health care system given histories of systematically racist projects like the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment, in which government officials lied to Black Americans in order to monitor untreated disease.

For conservative Americans, the hesitancy can come from a mistrust of the government and government-led directives, as well as a focus on individuality, Bednarczyk said.

The United States government has rarely had to mobilize the entire country behind such a large-scale and urgent public health effort, Bednarczyk said. For people already skeptical of the government, this emphasis can fuel concerns or misinformation.

Critics of a government-led effort emphasize the changing stances from federal leaders - from saying people did not need masks, to emphasizing the need to wear masks all the time, to this week dropping the mask guidelines for vaccinated individuals. They also questioned the seemingly contradictory shutdowns of some small businesses while large retailers could continue to operate.

Researchers should study the various motivations to avoid the vaccine, Bednarczyk said, but he cautioned against drawing hard conclusions from such trends.

"It's important to look at some of those groups, but we also have to be very careful when we're doing that because we don't want it to come off sounding like this group is bad because they don't want to get vaccinated," he said. "That's not what we're looking to do, so we're always very cautious in how we do these types of assessments."

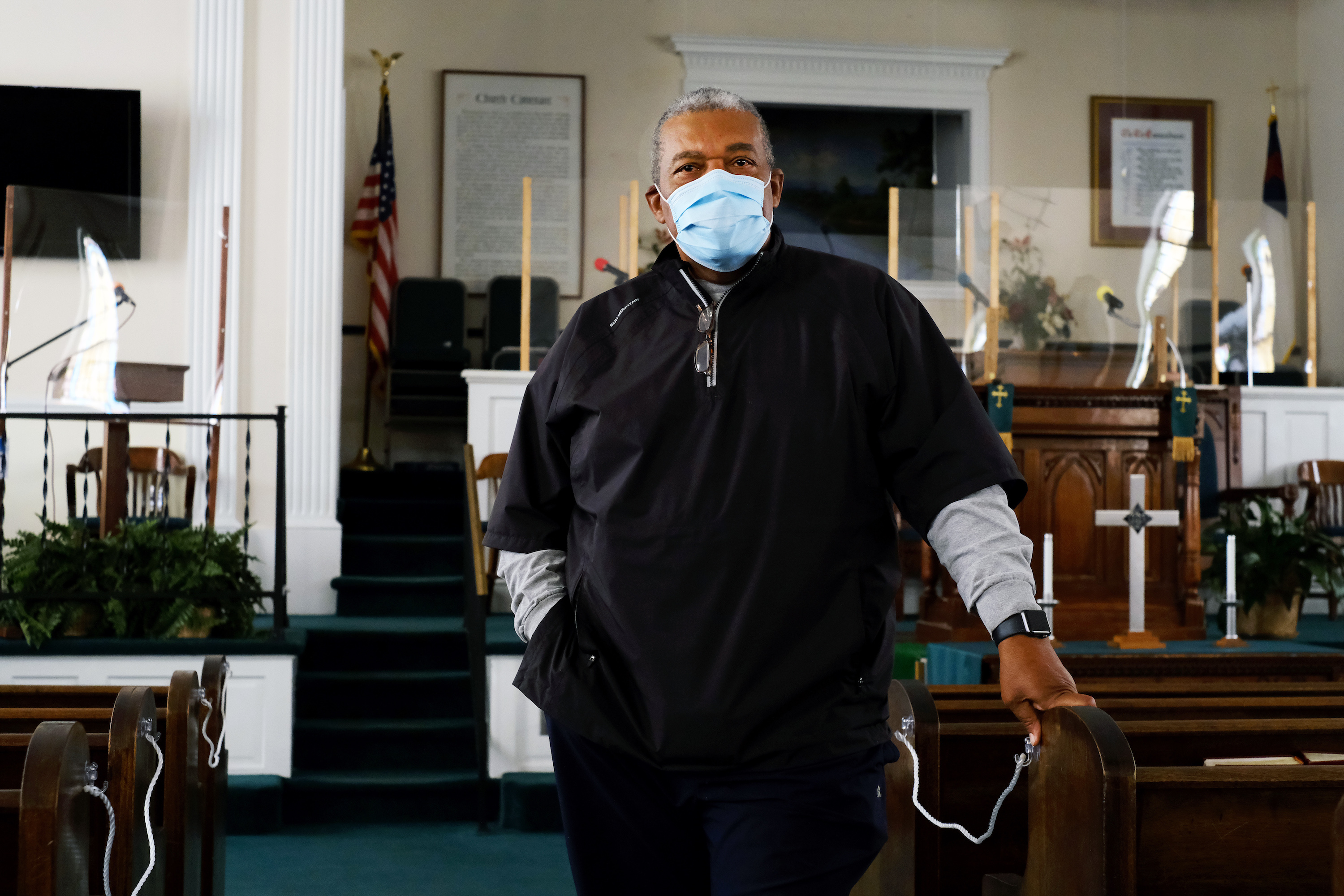

Staff photo by Wyatt Massey / The Rev. Steve Caudle, senior pastor of Greater Second Missionary Baptist Church, stands in the sanctuary of his church in Chattanooga on April 12, 2021. The pastor has worked with community partners to raise awareness about the COVID-19 vaccine and make sure people are getting appointments to get a dose.

Staff photo by Wyatt Massey / The Rev. Steve Caudle, senior pastor of Greater Second Missionary Baptist Church, stands in the sanctuary of his church in Chattanooga on April 12, 2021. The pastor has worked with community partners to raise awareness about the COVID-19 vaccine and make sure people are getting appointments to get a dose.

WWJD?

For people like Caudle, who spent weeks this spring ensuring those in his congregation knew about vaccine events or had an appointment, it is frustrating to see his neighbors, and even fellow Christians, turn down the vaccine.

Caudle has graduated from Dallas Theological Seminary and New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, two of the most conservative Christian schools in the country. He knows the theological frameworks of many evangelical pastors, but also knows that Christians read the same Bible.

"You ask yourself the question: WWJD? What would Jesus do? Jesus would take the vaccine. Jesus would wear the mask, because 'love your neighbor,'" Caudle said. "You're protecting your neighbor."

The Christians saying God will protect them from the virus or that they need faith, not a face covering, does not align with Caudle's understanding of the divine.

To Caudle, God provided advancements in science and medicine for the benefit of humanity. Taking a vaccine that can stop a virus that has killed 584,000 Americans and nearly 3.4 million people worldwide should be a no-brainer, he said.

"We can be so heavenly-minded that we do no earthly good," Caudle said. "I don't believe the gospel is that way. I believe it not only provides home in heaven but it provides justice and righteousness right here on earth. They have to both be in the gospel."

Yet, the public health approach to combat hesitancy that has involved people like Caudle and Jordan, when transferred to focus on white evangelicals, has provided mixed results.

In March, J.D. Greear, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, posted a photo of himself receiving the COVID-19 vaccine on Facebook and encouraged others to do the same. Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote in December that there is a moral responsibility to protect others through immunization. Robert Jeffress, senior pastor of the 14,000-member First Baptist Church in Dallas, announced a vaccination event at his megachurch this month.

But the public health strategy of using known or trusted sources to promote the vaccine, such as clergy, was found to have little effect on those most unwilling to take the vaccine, according to a hesitancy study from the Tennessee Department of Health released last month. The study found that overcoming hesitancy among rural, white conservatives poses the biggest challenge for Tennessee in improving the state's vaccination rate, which is among the lowest in the country.

Churches hosting vaccination events is not a guarantee of a high response rate, either. In April, Burks United Methodist Church in Hixson partnered with a local pharmacy to distribute first doses of the Moderna vaccine.

Bindy Lewis, the church's officer manager who helped organize the event, said they promoted the opportunity on social media and through the church newsletter. They put a sign by the road. Church members shared information through their neighborhood groups.

On the Sunday of the event, 12 people showed up, Lewis said.

"It seems like we've reached the point that people who haven't gotten it aren't going to get it or aren't interested in taking it," Lewis said.

Barnes said the county health department is hosting upcoming pop-up vaccine events and the state health department is developing a campaign to further address vaccine hesitancy.

Health officials have emphasized that the county residents being hospitalized or dying from the virus in recent weeks are people who were eligible for the vaccine.

Conversations between individuals and their doctors are one of the most effective ways to persuade vaccine-hesitant people, said Dr. Phil Burns, an Erlanger trustee and chairman of the Department of Surgery at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine Chattanooga, during an April 22 Erlanger Board of Trustees meeting.

Burns called on medical staff throughout the hospital, and the region, to have more of those conversations with patients.

"Maybe we can turn some of those people around," Burns said. "It staggers me that we have vaccination lines that are not full."

Contact Wyatt Massey at wmassey@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6249. Follow him on Twitter @news4mass.