The forest has many sounds. Birch trees creak; cicadas chirp; and mushrooms speak - but only if you're paying attention, says Ali Banks, 33, local herbalist and wildcrafter since 2012. She and her fiance Joe Zokan, 28, who has been wildcrafting for 10 years, are co-founders of Forest Folk Fungi, a local, plant- and fungi-based apothecary.

Wildcrafting, also known as foraging, refers to the practice of harvesting wild plants and fungi for food or medicine. It is an ancient art form, and one that Banks says "is about reciprocity and relationships of consent."

Among many Native American cultures, Banks explains, it is tradition to ask the organism's permission before harvest. Likewise, she says, after harvest, one should make an offering to the land. For instance, Banks and Zokan say that in exchange for its fruit, they might offer the forest a song.

Naturally, not every forager will play a flute for mushrooms. Yet still, to wildcraft is to cultivate a profound, almost mystical, relationship with the natural world and its many edible and medicinal species, which are especially abundant in the biologically rich Southeastern U.S.

In fact, many of these species are so prolific locally, they grow, quite literally, like weeds.

The broadleaf plantain [1], for example, is rich in iron. Goldenrod [2] is good for the kidneys. And stinging nettle [3] is so packed with minerals, it is considered a superfood. But before you grab a spade, Banks says, "Spend some time in the place. Learn the names of plants; learn their relationships to each other. And just listen."

When wildcrafting, ethics are everything. Here, five local foragers discuss the three tenets: sustainability, safety and legality.

Sustainability

The general rule, Banks says, is to never harvest more than 10 percent of a population.

"If you see a flower that you want to take home, if you don't see ten more of those same flowers, you ought to leave it alone," she says.

Many foragers even take special measures to bolster species' survival rates.

Matt Shigekawa, 38, who mostly forages for edible mushrooms, says, "You never pluck a mushroom. You cut it [at the base] so that you don't damage the mycelium."

Mycelium is the part of fungus that grows underground. It is like the organism's root, though it is more accurate to think of it like a tree, and the fruit that it bears is the mushroom. As long as the mycelium is left in tact, the fungus will fruit every season.

When Shigekawa harvests, he collects the mushrooms in a mesh bag rather than a plastic bag. Using a mesh bag, he explains, helps disperse the fungus' spores, which are like microscopic seeds.

"In one of my spots, I find chicken of the woods year after year - but always in a new place. I like to think that my walking around, dropping spores, has something to do with next year's growth," says Shigekawa, who has been a mushroom hunter for nine years.

Finds like chicken of the woods [4], famous for its chicken-like flavor, Shigekawa sells to restaurants such as Easy Bistro in downtown Chattanooga. The price fluctuates, but most recently, he says, chicken of the woods sold for $16 per pound. Morels [5], another beloved culinary mushroom, sold for $20 per pound.

In addition to mushrooms, other edible, wild-harvest plants popular among foragers include watercress [6], which belongs to the same plant family as kale, and wild violet [7], which contains high levels of vitamins A and C.

But one of the most coveted - and most profitable - plants to wildcraft is American ginseng [8], used for medicine more than for food and averaging between $500 and $600 per pound.

"There are million-dollar roots in the ground, but I'd have to go to Asia to find those," says Justin Carter, who co-owns Signal Mountain-based Daymoon Forage & Landscape with Amy Foster. Carter, 33, and Foster, 44, have both been working with native plants since they were teenagers. While Foster's specialty is fungi, Carter's is ginseng, a skill he says he learned from a third-generation ginseng hunter.

American ginseng grows primarily in the Appalachian and Ozark regions. It is revered for its root, which, after it is harvested, dried and ground, has a huge range of purported health benefits, from improved memory to cancer prevention.

But, as Banks explains, "When you dig the root of a plant, you're taking its life. It's not going to come back."

While American ginseng is not federally listed as endangered, in Tennessee it is listed as a species of concern, making it all the more important for foragers to follow sustainable harvest practices - as well as state-mandated ones.

In Tennessee, ginseng can be collected only between Sept. 1 and Dec. 31, and only if the plant has three or more leaves and red, ripe berries, indicating its maturity. When one of those plants is harvested, Carter says, "You take [the berries] off and plant them. Doing that gives the plant an 85 percent chance of growing another plant. [Otherwise, the berry] falls off, rolls away and gets eaten by a creature."

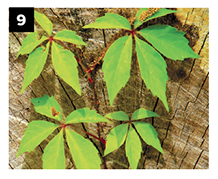

Unlike mushrooms, harvesting ginseng is hugely time intensive. The roots are delicate and any damage devalues the plant. To properly dig one root can take 45 minutes, Carter says. Moreover, ginseng is tricky to identify. It looks similar to several other species, including Virginia creeper [9], the bark of which can be brewed into cough syrup and whose leaves can be used to reduce inflammation.In the forest, there are countless species that benefit our bodies, but it's important to remember that they benefit the forest, too, Banks says.

Of course, it is equally important to remember that for all the species that can cure, there are just as many that can kill.

Safety

Zokan has a saying: "Anybody can eat any mushroom in the forest - once."

There are three types of poisonous mushroom: ones that affect the nervous system, ones that affect the gastrointestinal tract and ones that cause cell destruction and ultimately death.

"I don't know exactly how many different mushrooms could kill you, so I assume all of them do," Shigekawa says.

When it comes to safety, the more times a wildcrafter can cross-reference a species, the better.

The first step, all these foragers agree, is to familiarize oneself with a field guide - or 10 - and learn to identify plants and fungus.

"I want to see that one mushroom in ten different books and have each of those books say the same thing," Shigekawa says.

Online forums or social media sites such as Instagram, where foragers can post photos of their finds and crowd-source ID tips, are also helpful. Though, Banks advises, be sure to share only quality photos. Shoot the specimen from all angles; make sure the images aren't blurry. For mushrooms, Banks says, "Show me the underside of it. I need to see the gills."

Spore prints are another way to ID fungus. To make a spore print, the mushroom cap is placed on a piece of paper, gill-side down, allowing the spores to fall in an identifiable patter.

Ultimately it is up to that person to educate him or herself, says Foster, who frequently sells wild-harvested mushrooms to local restaurants such as St. John's, Cashew and FEED Co. Table & Tavern. Likewise, Foster says, "It is the chef's responsibility to know what he or she is buying. I took hedgehogs to St. John's once, and those are really hard to find around here. [The chef] opened the bag and said, 'Hedgehogs. Nice!' She knew exactly what she was looking at."

Furthermore, adds Shigekawa, "I would never sell anything that I didn't try first. And I would study it to the core before trying it myself."

But beyond consumption, the act of wildcrafting comes with risk, too.

"Know your surroundings," Shigekawa advises. "Don't go out alone. Have a GPS on your phone. Wear proper gear. You're going to be out in snakey areas, walking around in poison ivy, ticks everywhere. It can be a dirty, dangerous job."

Even more so should a forager stumble onto the wrong property.

Legality

For the sake of safety and legality, foraging on private property - with permission - is the best practice. This might include friends' or neighbors' lands.

"You learn to develop an eye for where mushrooms might be growing," Shigekawa says. "I keep bags and coolers in my van, just in case."

Should he see a flush of fungus growing in a person's yard, Shigekawa will stop, knock on the door and ask permission to harvest.

"I've never had anybody say no," Shigekawa says. Though, several years ago, in a neighborhood in Apison, Tennessee, he spotted a hardwood covered with oyster mushrooms, a popular, mild-tasting culinary mushroom.

"I knocked, but [the person] wasn't home. I took the mushrooms anyway and left a note with my phone number and a $20 check. I said, 'I'm sorry I took this off your tree. If you feel like I owe you more, call me.' He called me later that night and started laughing and said he'd ripped up the check. He said, 'Anytime you see them on that tree, you're welcome to them,'" Shigekawa says.

Foraging on public lands becomes trickier.

For example, Chattanooga city code deems it unlawful to remove any "tree, shrub, fern, plant or flower" from public parks or playgrounds, which includes areas such as Stringer's Ridge, Greenway Farm and the Tennessee Riverwalk.

Tennessee state parks, however, allow the collection of plants or mushrooms for personal use, but not for commercial use. Georgia state parks prohibit the collection of any wildlife.

Meanwhile, Cherokee National Forest, which is cooperatively managed by state and federal resources, requires a permit for the collection of virtually any wildlife on its land. For example, every year, the U.S. Forest Service issues a limited number of permits to harvest wild ginseng in the national forest. In 2016, it issued 40 permits, each allowing for the harvest of 25 roots (about a quarter-pound) only between Sept. 16 and Sept. 30.

Because policies and laws vary among local, state and federally managed lands, a wildcrafter should always do due diligence and contact officials for rules on public lands. He or she should also know the difference between private and public open spaces.

More than just field guides, the ethical wildcrafter studies land.

"To some people, the woods is just a sea of green. You have to fine tune your lens to recognize different plant communities, and then you start to see the forest differently," Zokan says.

Banks adds, "The moment you clip a plant and take part of its body, you have a great responsibility to that place. Maybe you clean up trash or fight for protection of that place. Reciprocity looks different to everyone."