For answers to frequently asked questions about the coronavirus, click here.

Research scientists Dawn Richards and Elizabeth Forrester watched concern grow as a new coronavirus causing pneumonia-like illness emerged in China, then spread to Europe and the United States.

The worry they saw from their students at Baylor School mixed with chatter they began hearing around town. Someone's friend has a cough. A family member developed a fever. But even as the virus reached Chattanooga, those people could not get answers to their burning question: Do I have COVID-19?

Just over a week ago, on March 13, Hamilton County confirmed its first case of COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus. As of Saturday, Hamilton County had confirmed eight cases total. But lessons learned from other states and countries suggest that the virus has likely been circulating locally for weeks, with far more cases going undetected than actually reported.

Whereas some countries - such as South Korea and Singapore - quickly developed testing mechanisms to aggressively track where the virus was spreading, testing efforts in the United States have been plagued by delayed production, limited supplies, stringent criteria and bureaucratic red tape. To compound the issue, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initially produced some testing kits with a faulty component. Now, communities across the country are scrambling.

Accurate and timely testing is key to controlling the spread of coronavirus.

Testing decision

*There is currently no rapid test for coronavirus like there is for influenza, so being tested for COVID-19 is harder than you might think. Here’s why:You must first call the health care provider you plan to see. Because we’re in the midst of a global pandemic, there are special protocols and supplies are limited. You cannot show up to a clinic, lab, or any medical facility and request testing.The provider will determine over the phone if you qualify for screening. Currently, testing is only available to individuals with specific symptoms: fever over 100.4, cough, trouble breathing, as well as individuals who within 14 days of symptom onset had close contact with a suspect or laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patient, or who have a history of travel from affected geographic areas within 14 days of their symptom onset.If the provider decides you need a test, they will tell you the next step, which requires them to take a sample specimen using a nasal swab. In the meantime, stay isolated at home to prevent potential spread to others.Ultimately, it’s up to the provider whether or not to test a patient for COVID-19. Providers may consider other conditions and risk factors in addition to symptoms.

Testing allows medical providers and public health workers to detect and isolate infected individuals - our best defense against a highly infectious disease that has no vaccine to prevent it or drugs to cure it. It also expands surveillance capabilities, helping track where the virus is circulating and trace people with known exposure. Then, they can be isolated and tested, too, rather than unknowingly spreading the disease further throughout the population. Health care workers who are exposed to the virus but test negative can go immediately back to the frontline. Valuable resources and lives are saved as a result.

Forrester, a biochemist with a doctorate in cancer biology, teaches advanced placement biology at Baylor. Since there's no treatment for coronavirus other than supportive care, she said testing is more a public health necessity than a medical one.

"Clinically, if a patient has pneumonia, you treat it the same whether it's just pneumonia or pneumonia that's from COVID-19," Forrester said. "But we need the data, because we need to know how many people are currently infected so that we can model where it's going next. That's been the difficult thing with the lack of testing. We just really don't know where the virus is."

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses, some of which cause respiratory illness in humans, but mostly circulate among animals, including camels, cats and bats. They were thought to only cause the common cold until SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, and MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome, emerged.

SARS - which first appeared in China in 2002 - and MERS - which emerged in Saudi Arabia in 2012 - sent shockwaves through the countries they affected. About 10% of people with SARS die, and MERS kills about 35% of those who contract the virus. However, the virsuses have for the most part spared Western nations.

Clint Smith, a virologist who specializes in coronaviruses at the University of the South, said lessons learned from previous SARS and MERS outbreaks help explain why some countries quickly mobilized to contain the new coronavirus, and others, such as the United States, took a more conservative approach.

"There's this perception that coronavirus aren't necessarily a European problem or a U.S. problem," Smith said. "I think there was some complacency and hopes that this being the third recent coronavirus emergence in humans it would behave similarly - that it would be relatively easy to control."

Smith said the initial public health narrative that COVID-19 was similar to influenza further dampened our response.

"It's really hard to get people in a normal year to get their flu shots despite the fact that it kills tens of thousands of people," he said. "It is a familiar enemy, so that early comparison - though it was a helpful analogy to perhaps disseminate information - lead to the inability for many individuals to recognize the potential severity of this current situation."

COVID-19 is more deadly than seasonal influenza. It causes mild illness - fever, cough, trouble breathing - in about 80% of the people it infects. The other 20%, typically older adults and those with underlying medical conditions, develop pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Approximately 3.4% of infected individuals will die, according to the World Health Organization's latest estimates, though our understanding of the disease is still evolving. Seasonal flu mortality is usually less than 0.1%.

We're also better prepared for influenza, including pandemics.

"We have a global system for influenza, a vast surveillance network that collects a tremendous amount of data," Smith said. "There's a tremendous amount of infrastructure, because we deal with influenza on a seasonal basis. There are established tests that are rapid and very easy to administer in a health care setting."

Researchers are working tirelessly to develop a rapid test for coronavirus. Until that happens, our only test in the U.S. requires sophisticated laboratory equipment and professionals capable of analyzing the specimens.

The countries who have responded best to coronavirus understood the gravity.

Testing steps

*“Testing” is often used to explain the whole process of determining if a patient has COVID-19, but this can be confusing. That’s because there are many steps along the way.The provider will use a nasal swab to collect the sample and then send it to a laboratory capable of analyzing the specimen, because there is currently no rapid test for coronavirus.The sample is then shipped to a special lab capable of testing for COVID-19. It typically takes between 48 hours and seven days to obtain results. However, due to the current backlog, most providers in the Chattanooga region report test results taking closer to seven days.At the lab, a scientist must spend several hours processing a specimen. There are also many needed supplies, such as reagents, protective gear and sample trays that are in short supply and high demand across the world. Missing any of these can cause a delay in results.

South Korea - which was hit hard by MERS in 2015 - prioritized aggressive early testing. The country quickly secured needed supplies and made sampling accessible in ways that limited person-to-person contact by using drive-through sites. Singapore followed similar strategies and even developed a blood test to look for antibodies that are a sign of previous infection.

Meanwhile, the U.S. downplayed the potential spread, failed to ramp up production of testing materials and maintained stringent testing criteria that prioritizes people with symptoms who have either traveled to a high-risk area or come into contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19, meaning the vast majority of Americans don't qualify for testing.

Experts say that the U.S. trajectory currently mirrors the start of the coronavirus outbreak in Italy, which on Thursday surpassed China - a country with a population nearly 23 times its size - as the country with the most coronavirus-related deaths.

Smith said the problem with lackluster testing is once cases get into the thousands, it becomes exceptionally difficult - if not impossible - to implement the containment measures known to control spread of coronavirus.

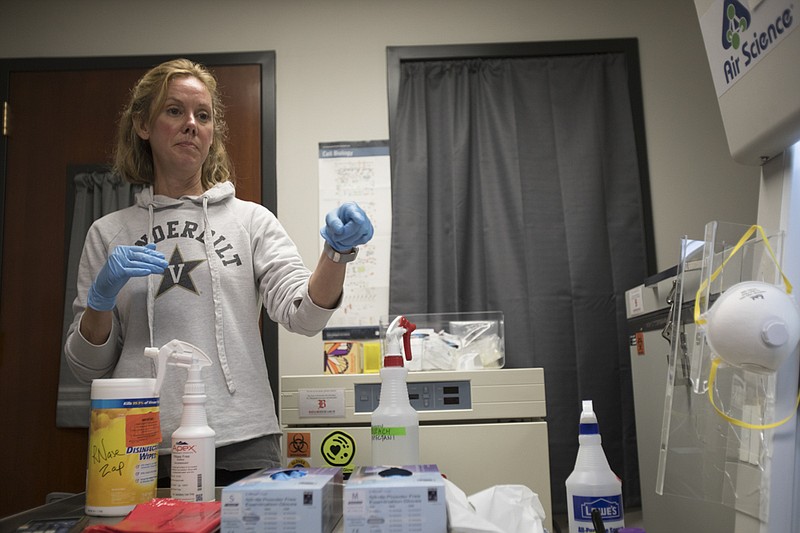

As scientists, Richards and Forrester know the need for Southeast Tennessee to expand its testing capabilities. That's why when they started catching wind that COVID-19 might be in Chattanooga, they snapped into action.

Currently in Hamilton County, it can take up to seven days from the time a medical provider obtains a suspected COVID-19 sample from a patient to the time that patient knows whether they're infected. A big part of the bottleneck is because few laboratories in the region have the equipment and personnel capable of analyzing a test sample.

But everything needed to test for the virus was in a laboratory at Baylor. So when the FDA issued an emergency use authorization of the CDC test kit, making materials more accessible to complete the technique used to test a specimen for the virus, Forrester called Richards, chairwoman of Baylor's science department and an molecular microbiologist with a doctoral degree in oceanography.

"She called me and said, 'We can do this. It's been released, and the protocol's out there,'" Richards said. All they needed were the reagents, or the ingredients used to conduct the technique that tests for COVID-19.

The Weeks Science Building on Baylor's campus is supported by a $15 million endowment from the estate of Katherine Weeks. The money is designated for building maintenance and to support the academic programs and faculty of the science department, who have access to technologies that are normally found only at universities and research institutions.

Like many research scientists, Forrester, Richards and their students regularly use a technique called an assay to identify the genetic material of common viruses. It's the same technique, and currently the only way to analyze specimens for COVID-19. It works by isolating and amplifying a genetic signature specific to the virus.

While the method is common in research labs, it is not something that most hospitals and doctor's offices are equipped to do. That's why Forrester and Richards want to help with the current need to ramp up local testing efforts until a more simple, rapid test is available.

"This test is actually fast. Once we have a specimen in hand, processing is less than four hours," Forrester said. "The problem is that we have a few labs that are able to run it. And so there's a backlog of samples, which is, I think, why we're seeing this delay on turn around."

They got the materials and began to practice running tests last Thursday, right in the Baylor classroom.

"Our students are smart, and they were watching us these last few days of school," Richards said. "We had several students come and say, 'We could do this in here, couldn't we?'"

The two had the test down by Friday. By then Chattanooga was under a state of emergency and schools were suspended for the month because of the coronavirus.

"We just had some really, really late nights and long days to figure it out, and once you've got it figured out, you've got it," Richards said.

Now, they are working through the final steps of the approval process and expect to be able to test actual samples from patients in the coming days. Local lawmakers, including U.S. Rep. Chuck Fleischmann, R-Tenn., have also advocated for Baylor.

"I put this as a priority for me," Fleischmann said. "Our nation, and I'm not pointing political blame, but our nation, as many other nations, was ill prepared at the onset to do the appropriate screening. That's where the ball was dropped. I'm just so proud of the Baylor School for stepping up and wanting to serve the community in this way."

Vanderbilt University Medical Center began in-house testing in partnership with its researchers about 12 days ago, according to spokesman John Howser.

"We've gone from being able to just run a few of these every day to yesterday they hit another kind of high mark. For the previous 24-hour period, they were able to complete 584 tests," Howser said on Thursday.

Richards believes that one reason why the Nashville area has so many more confirmed COVID-19 cases than other parts of the state is because that's where Vanderbilt and the state public health lab are located - so the turnaround time for testing is quicker. If given the resources to scale up, Baylor believes it could bring that same testing capacity to Chattanooga.

"That's our goal. We really, really hope that we can share this with the community," Richards said. "We're just waiting to be able to actually help."

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.