IF YOU GOWhat: VIDALIA ONION MUSEUMWhere: 100 Vidalia Sweet Onion Drive, Vidalia, Ga.When: Monday-Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.Website: http://www.vidaliaonion.org;Phone: 912-538-8687.Tickets: No admission fee.

VIDALIA, Ga. - They've started fistfights and court battles, been romanticized in country songs and counterfeited by bootleggers. Their trademark sweetness has made them a coveted ingredient in recipes from salads and relishes to cookies and muffins.

If a museum dedicated to onions sounds rooted in folly, the history behind the famous Vidalia onion can likely hold its own with other veggie shrines such as the Idaho Potato Museum, the Red River Valley Sugarbeet Museum in Minnesota and the tiny Carrot Museum tucked in a Rhode Island bed-and-breakfast.

The freshly opened Vidalia Onion Museum digs fairly deep to dish the good, the bad and the yummy on Georgia's official state vegetable - including the unearthed origin of Vidalias' reputation for being so sweet they can be eaten like apples.

"You go anywhere in the country and you get these crazy, random museums. So naturally people expected we had an onion museum," said Wendy Brannen, who oversaw creation of the museum in her job as executive director of the Vidalia Onion Committee, which handles marketing of the crop.

It took five years and $250,000. But the onion museum, which shares space with Brannen's committee offices and the local tourism bureau, opened its doors April 29 to coincide with the celebration of the spring harvest.

The museum has exhibits on the science behind why onions grown in rural southern Georgia turn out so mild (low-sulfur soil, for starters).

Only 20 counties in Georgia can grow and sell onions under the Vidalia name, by order of state and federal law. Each year onion farmers ship about 200 million pounds of Vidalias, valued at $150 million.

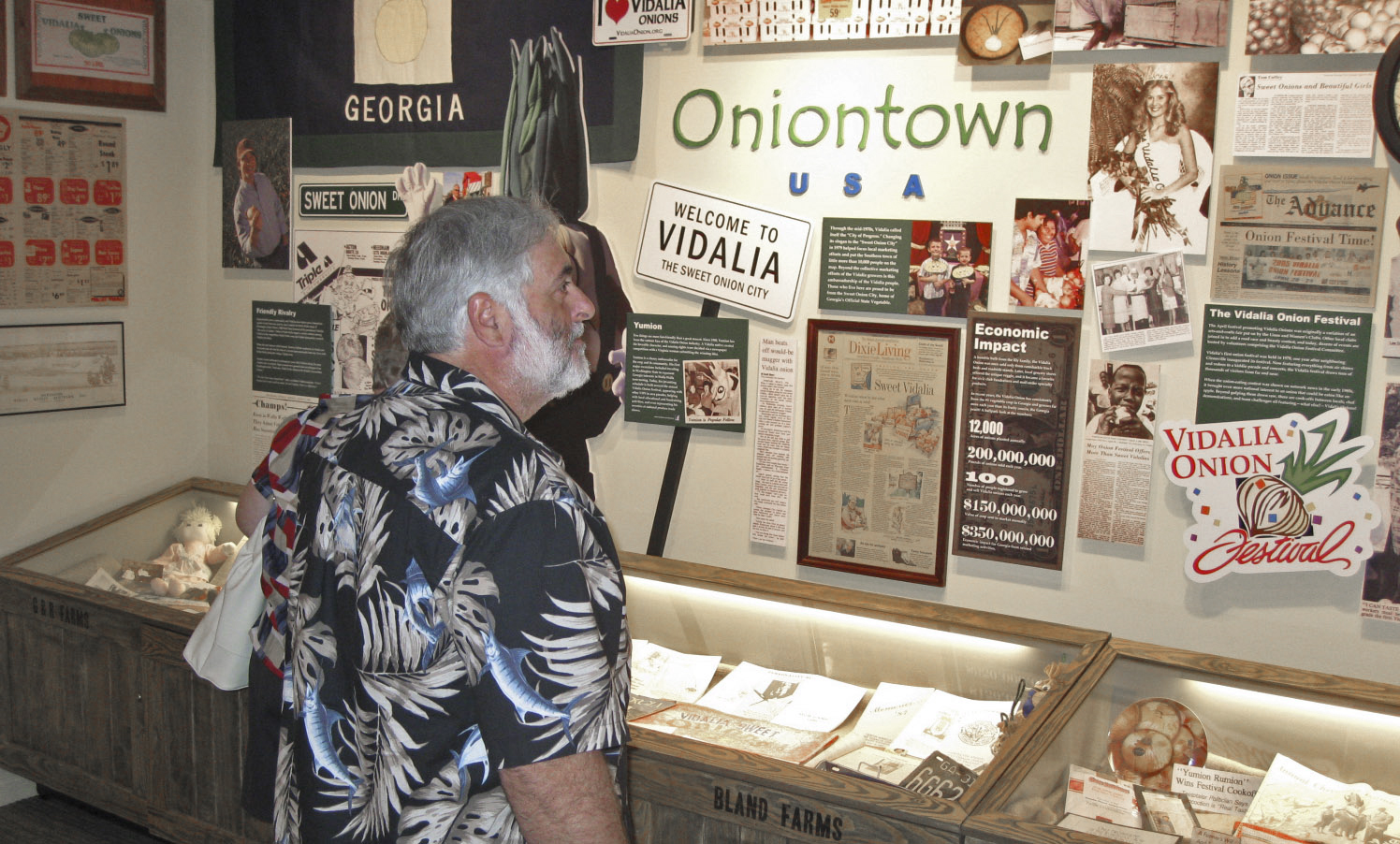

The museum's juicy centerpiece is a collection of photos, newspaper clippings and videotaped interviews that tell the story of how Georgia's prized cash crop grew from a few Depression-era farmers who randomly started growing onions to supplement their cotton and tobacco harvests.

One of those early stories features a firsthand account from farmer Mose Coleman, who grew his first onions from mail-ordered seeds in the 1930s and sold them out of a trailer made from the back of a Model T Ford. Coleman tells of how he sold his crop to a grocery chain's buyer by biting into a raw, ripe onion and eating it like a piece of fruit.

"I pulled out my onion and I ate it there in front of him," Coleman recalled in a speech years ago in Vidalia. "He'd never seen anything like it. There wasn't any tears coming out of my eyes, and I wasn't making no face."

The Vidalia onion's reputation rippled outward over the decades. A state farmer's market established here in 1949 sold onions to consumers traveling in from Macon, Savannah and Augusta. In the 1960s, Vidalia-headquartered Piggly Wiggly supermarkets began buying the onions by the truckload and selling them across the South.

It took a while for farmers to settle on the Vidalia name. Grower Pinky McRae insisted on calling his onions "Toombs County Sweets." Others stood by "Glennville Sweets," named for a neighboring farming town. Disputes over what to call the onions grew so heated they sometimes erupted into fistfights.

By the 1980s, Vidalia farmers put aside their infighting to face a common foe: bootleggers who were shipping onions from Texas into Georgia and bagging them with Vidalia labels to fetch premium prices.

Newspaper clippings chronicle tales of onion intrigue. One farmer hired a private investigator to go undercover and spy on a suspicious competitor. Another grower was reported to have borrowed a gadget from Coca-Cola and so he could sneak into a neighbor's fields and test the sugar content of his onions.

By 1985, one farmer accused of selling bogus Vidalias got hauled into court, but growers couldn't make fraud charges stick. Nothing in state law defined what made an onion a Vidalia.

Farmers began lobbying state lawmakers and Congress. In 1986, the 20-county Vidalia onion growing area was defined in Georgia law. It won federal protection in 1989.

The onion battles made headlines across America, and the crop's legend grew. Vidalia Mayor Ronnie Dixon says he realized his city's namesake onions had become downright famous soon after he took office in 1994.

"People started calling city hall and asking how they could get onions mailed to them," Dixon said.

Even though the town's a bit off the beaten path, about 15 miles south of Interstate 16 between Macon and Savannah, plenty of pilgrims have been finding their way to the museum. There, onions grow in patches planted on either side of the front door. In less than two months, more than 250 visitors have signed the museum's guest book.

Mark Labat and Barbara Ouder of Slidell, La., wandered in on a recent Tuesday. After vacationing in Savannah, they opted to make a special detour through Vidalia rather than head to Plains, Georgia's peanut capital and home to former President Jimmy Carter - who made sure the White House kitchen stocked Vidalia onions.

"We were looking at a map, wondering where could we go," said Labat, an auto mechanic. "I said I'd rather go to Vidalia. You can't do Louisiana cooking without onions."