WHAT SPEED DO YOU NEED?RESIDENTIAL HOUSEHOLD BROADBAND GUIDEEmailing, web surfing, streaming basic video• One user on one device: 1 to 2 mbps• Two users or two devices at once: 1 to 2 mbps• Three users: 1 to 2 megabits per second• Four users: 6 to 15 mbpsRunning one high-demand application, like online gaming, HD video, video conferencing• One user: 1 to 2 mbps• Two users: 1 to 2 mbps• Three users: 6 to 15 mbps• Four users: 6 to 15 mbpsRunning multiple high-demand applications at the same time, i.e. gaming while video conferencing• One user: 6 to 15 mbps• Two users: More than 15 mbps• Three users: More than 15 mbps• Four users: More than 15 mbpsBROADBAND BY THE NUMBERS• 19 million Americans have no access to fixed broadband• 14.5 million of those Americans live in rural areas• 100 million Americans don't subscribe to broadband even when it's available• 85 percent of Americans with access to broadband use cable providers• 18 percent of Americans with acces to broadband use fiber providersSource: Federal Communications Commission

Jed Arthur was at his wits' end.

He lives on a remote road in Polk County, Tenn., and runs a successful tire business, Jed's Wholesale Tires, out of a warehouse just 300 yards from his house. His son and daughter-in-law live next door. He's fourth, maybe fifth generation Polk County, named after "The Beverly Hillbillies" character and proud of it. (No one ever forgets his name once he tells them that, he said.)

He and his nine employees have been selling tires since 1990, peddling on Amazon, eBay and the company's own websites. At least 50 percent of Arthur's business comes directly from online -- but for years, Arthur ran the business on a measly 1.5 megabits-per-second Internet line, and dished out $800 a month for it.

With seven computers plugged into that line, it took three minutes just to upload a photo. Sometimes, Arthur would start an upgrade at 6 p.m. and it still wouldn't be done at 8 a.m. the next day. His employees were wasting valuable time.

But Arthur couldn't figure out a way to get faster Internet. None of the big commercial carriers ran fiber-optic lines all the way out to Jed's Wholesale Tires. He tried using mobile broadband -- the 4G connection used on most smart phones -- but kept exceeding data limits. He tried satellite Internet and ran into the same problem.

"They either don't have fast-enough speeds or they bottleneck you," he said. "We had tried and tried and tried, and finally I just about gave up."

He'd have to move the business to somewhere with faster Internet speeds, he decided. By the end of last year, Arthur had scoped two possible locations in Cleveland, Tenn.

"I walk to work every morning, and I love that," he said. "But business is business."

Arthur lives just an hour's drive from Chattanooga -- just an hour's drive from the Gig City, where gigabit-per-second Internet sells for $69.99 a month and entrepreneurs have trouble figuring out how to use all that bandwidth. He's an hour's drive from speeds about 1,000 times faster than his $800 megabit-and-a-half line.

In the shadow of the gig, there are hundreds of people -- nearly all in rural areas -- who can't access even basic broadband Internet. (That's defined by the Federal Communications Commission as 1 mbps upload and 4 mbps download speeds -- still more than 200 times slower than Chattanooga's gig, but adequate for most common Internet uses on one device.)

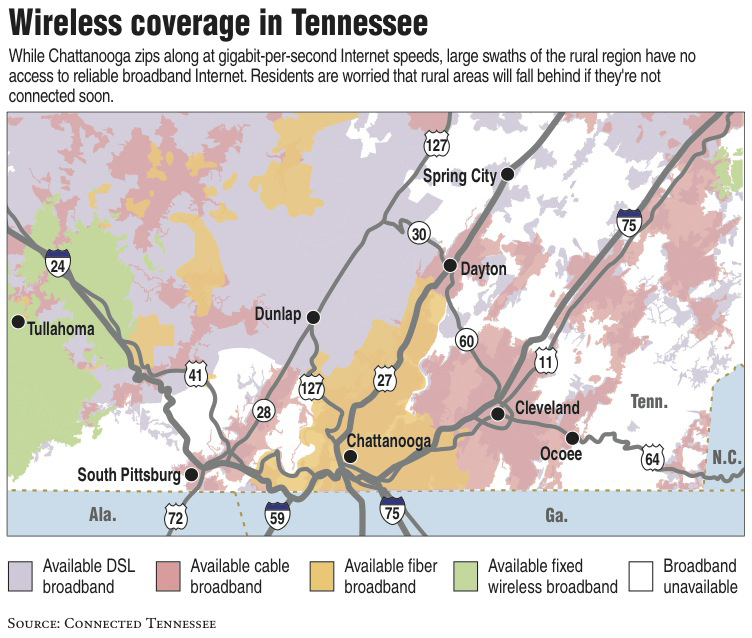

"It is a tale of two districts," said Corey Johns, executive director of Connected Tennessee, a statewide organization that tracks and works to improve broadband coverage in Tennessee.

About 8 percent of Tennessee's households have no access to broadband, according to Connected Tennessee. In Northwest Georgia, about 5 percent of households are unserved, the Georgia Technology Association reports.

In a world where everything from college classes to paying bills is done online, the lack of access spells trouble for rural areas, Polk County Executive Hoyt Firestone said.

"It's not a luxury," he said. "Broadband is a necessity in today's environment. It's today's pathway for economic development. Just like the highway improvement acts and the interstate system -- Internet service can do that for telecommunications. If we can't acquire the same service as the larger urban areas, we're going to fall way behind."

Yet despite potential customers who are practically begging for Internet providers to expand to their areas, the big players so far haven't pulled the trigger on very rural broadband. That's because it's hard to make a profit on rural lines, said Mark Wigfield, FCC spokesman.

It's expensive to add the miles of new line required to reach rural residents, and the density of households along that line is usually very low -- which means there aren't a lot of subscribers out there to help the provider recoup the cost of the line and eventually turn a profit.

Arthur got lucky. Comcast agreed to run a line out to Jed's Wholesale Tires and pick up the $10,500 tab. Arthur signed a three-year contract and pays $650 a month for phone and Internet service. Since January, he's been flying along at 100 mbps speeds. Now uploading a photo takes just 15 seconds, instead of three minutes. Now customers can log on and order 24/7. Now he can access his computers remotely and work from home.

"It was a hard fight, a lot of hard work and some lucky connections, or we'd be sitting here in a mess," he said.

But others are still waiting. And as the years tick by without progress, some rural residents have had enough. They're binding together in groups of 50, 100, 150 to ask Internet providers to run broadband lines to their neighborhoods. Joyce Coltrin is leading the charge in southwest Bradley County. She lives in Ooltewah, but her grandchildren live in Bradley and she runs a business in the area.

"For years, over and over we kept hearing that we were about to get broadband in our area," she said. "But you get to a point where you think, 'No, I'm not going to wait any longer; we need to do something.'"

She decided to rally her neighbors but hit an immediate roadblock.

"Surprisingly, it is very difficult to organize because we don't have Internet," she said, with a half-laugh. "So you practically have to go door-to-door. And what if you miss them? Go back again. It's very difficult."

Still, she's signed up about 150 people.

"The Internet has gone to everyplace else," she said. "The only way you get something done is to make noise."

THE SATELLITE SOLUTION

A wired broadband connection isn't the only way to access the Internet, of course. There are satellite services, mobile broadband hotspots, fixed wireless, dial-up and DSL. Besides wired broadband, satellite Internet is one of the most promising current solutions for rural areas.

"If our rural communities can't have access to the high speed, an industrial park is really nothing more than an electrified cow pasture."- Tennessee Sen. Janice Bowling, R-Tullahoma, on broadband high-speed Internet

Satellite Internet company ViaSat can now provide upload speeds of 3 mbps and download speeds as fast as 12 mbps, vice president Lloyd Riddle said. Prices range from $50 to $130 a month, with data caps between 10 gigabytes and 25 gigabits a month. ViaSat also offers a free zone from midnight to 5 a.m., where any downloads don't count against the data cap.

"We're not just fixing the last gaps in Tennessee, we're fixing the last gaps in the world," Riddle said. "Satellite may play a major role in that, because it may be the only way to get it done."

ViaSat serves about 600,000 customers, and the company's new satellite was launched just two years ago.

"People think satellite has been around for a while, but not this satellite Internet," he said. "This has been available for about two years, and it's not in the same category as what was available. It's 12 times faster."

But satellite is still a makeshift solution, Johns said. The major challenge is latency -- that jittery cut-in-and-out that happens when a video freezes and restarts.

"It takes time for the signals to bounce from your home to the satellite, off the satellite, to the focus point and back in the network," he said. "If you're a downloader and you don't have any other options, then that's a good option. But if you do video conferencing or remote live-stream consultations with your physician, or if you send a data file to a website with cloud-based tech, that's when the upload speeds really get you."

Take Michelle Rymer. She and her husband raise 170,000 chicken every six weeks on their poultry farm in Bradley County, and to be competitive Rymer needs those chickens need to be housed in just-right conditions. So they've installed an alarm system: If conditions get too hot, or the power goes out, or the automatic feeders malfunction, the alarm alerts the Rymers. The alarm is critical.

"Depending on the age of your chicken, you can lose 170,000 chickens in a matter of minutes if something goes wrong," Rymer said.

The best alarm systems run on high-speed Internet, but the Rymers don't have access to broadband. So they're stuck using an outdated, less-reliable system. The family uses a Verizon hotspot to connect to the Internet, paying more than $100 a month to use no more than 10 gigabytes of data at 3G speeds.

She's tried satellite Internet, but it's unreliable in her area. Other options are too slow.

"It severely limits us," she said. "I homeschool my kids, and there are several excellent educational tutorials and online classes I have not been able to access for my children because I have very limited Internet capability."

She can't stream Netflix with her hotspot, and downloading a regular 90-minute movie will use about 2 gigabytes of her 10-gigabyte monthly data limit.

"And since we only get 3G coverage, it might not even download all the way," she added.

For people like Rymer, wired broadband is the only viable solution -- and that's one reason why state legislators and the FCC are rolling out new programs and laws aimed at increasing rural broadband access. State Sen. Janice Bowling, R-Tullahoma, believes the best solution is in public-private partnerships.

She sponsored a bill this year that would allow municipal electric utilities to expand their broadband services outside their electric service areas. Right now, for example, EPB can only provide gigabit Internet within its predefined service area -- Hamilton County and parts of North Georgia. Bowling's bill would give EPB the legal right to provide Internet beyond that border -- when invited and in areas that butt against EPB's service area.

"If a developer, whether industrial, residential or medical, says I'll need high-speed Internet and there is no commercial provider willing to provide 100 mbps symmetrical or fiber optics, they could invite one of the fiber-optics communities, like EPB, to come in and make a bid and provide this service," Bowling explained.

The bill stalled this year, but Bowling said the momentum is growing. She's put together a committee with Sen. Jack Johnson, R-Franklin, to study the issue, pull users and providers together to vet the idea, and bring a revised bill back in January 2015.

"Arguably, broadband high-speed Internet is the electricity of the 21st century," she said. "If our rural communities can't have access to the high speed, an industrial park is really nothing more than an electrified cow pasture."

ESSENTIAL SERVICE

In the past two years, the FCC has given $26.2 million to companies in Tennessee and $25.5 million to companies in Georgia to expand the rural broadband network. And that's just a toe-dipping.

The FCC is jumping into the fray with the $4.1 billion Connect America Fund, a new division of the FCC's Universal Service Fund that will give providers financial incentives to build into rural areas. The Universal Service Fund was established in 1934 to build telephone lines into remote areas, and now the FCC is pivoting some of those funds to instead focus on broadband expansion.

"The FCC reached the conclusion that broadband service is as essential today as phone service was a century ago," Wigfield said. "Consumers use it to stay in touch, the government uses it to reach people, schools use it for education, businesses use it for competing in a worldwide marketplace -- we all use it constantly."

Right now, phone companies receive subsidies from the FCC's Universal Service Fund. As the Connect America program rolls out, large phone companies will be required to provide broadband in order to continue receiving those subsidies and earn the additional broadband incentives.

The large providers -- there are different rules for the small telephone companies -- have a right to refuse to add broadband, which would free the FCC's incentives up for another company to claim. Other carriers would then bid for a chance to claim that money and build the broadband, Wigfield said.

"It's a long-term overhaul of the rural phone subsidy system to make it into a broadband program," he said.

Connect America phase one already has funded broadband expansions in Marion, Rhea, Meigs, McMinn, Bradley and Polk counties in Tennessee, as well as Whitfield and Walker counties in Georgia. Phase two funding should be available by the end of 2014, Wigfield said.

But whatever happens now is too late for Rosy Daly, who lives in Meigs County. After her husband died, she put her big log home on the market. A couple from Virginia made an offer and Daly accepted, thrilled to sell the house.

But before the sale could close, the buyers backed out. The wife worked for the federal government, and she telecommuted to Virginia. She needed reliable high-speed Internet. And the only suitable Internet they could find was mobile broadband from Verizon, for $300 a month.

"And that was cost prohibitive," Daly said. "They finally closed on a house in Hamilton County. So we lost some good people."

Contact staff writer Shelly Bradbury at 423-757-6525 or sbradbury@timesfreepress.com.