View our Civil War Sequicentennial site

Two mules at once! What a shot! The hexagonal-shaped bullet passed through both necks of a pair of Union army mules side by side in harness as they navigated the narrow mountain road to get supplies to starving Union army troops inside Chattanooga.

The Alabamians ensconced on Raccoon Mountain in early October 1863 never forgot that shot, or their duty in the gorge of the Tennessee River.

After Chickamauga, the besieged Union troops in Chattanooga depended on a supply base at Bridgeport, Ala. The most direct path for supplies ran from Bridgeport through Lookout Valley to Chattanooga. When the Confederate army occupied Lookout Mountain, the direct route from Bridgeport was closed. The next alternative to bring supplies north was from Bridgeport to Sequatchie Valley, then east using a road known as Haley's Trace (mostly today's Suck Creek Road) through the narrow gorge between Raccoon Mountain (now Elder Mountain) and Walden's Ridge, then cross the river to the south shore on a pontoon bridge (near today's Olgiati Bridge), and enter Chattanooga.

In early October, men from the 4th Alabama Infantry, which included a company from nearby Jackson County, were ordered to the northern end of Raccoon Mountain to stop the Yankee wagons along Haley's Trace.

Assigned to duty with the Alabamians were six men armed with a highly accurate, hexagonal-bored sharpshooter's rifle, commonly called the Whitworth, which claimed capability of hitting targets as far away as a mile. These guns, made in England, were the most accurate firearm of the day.

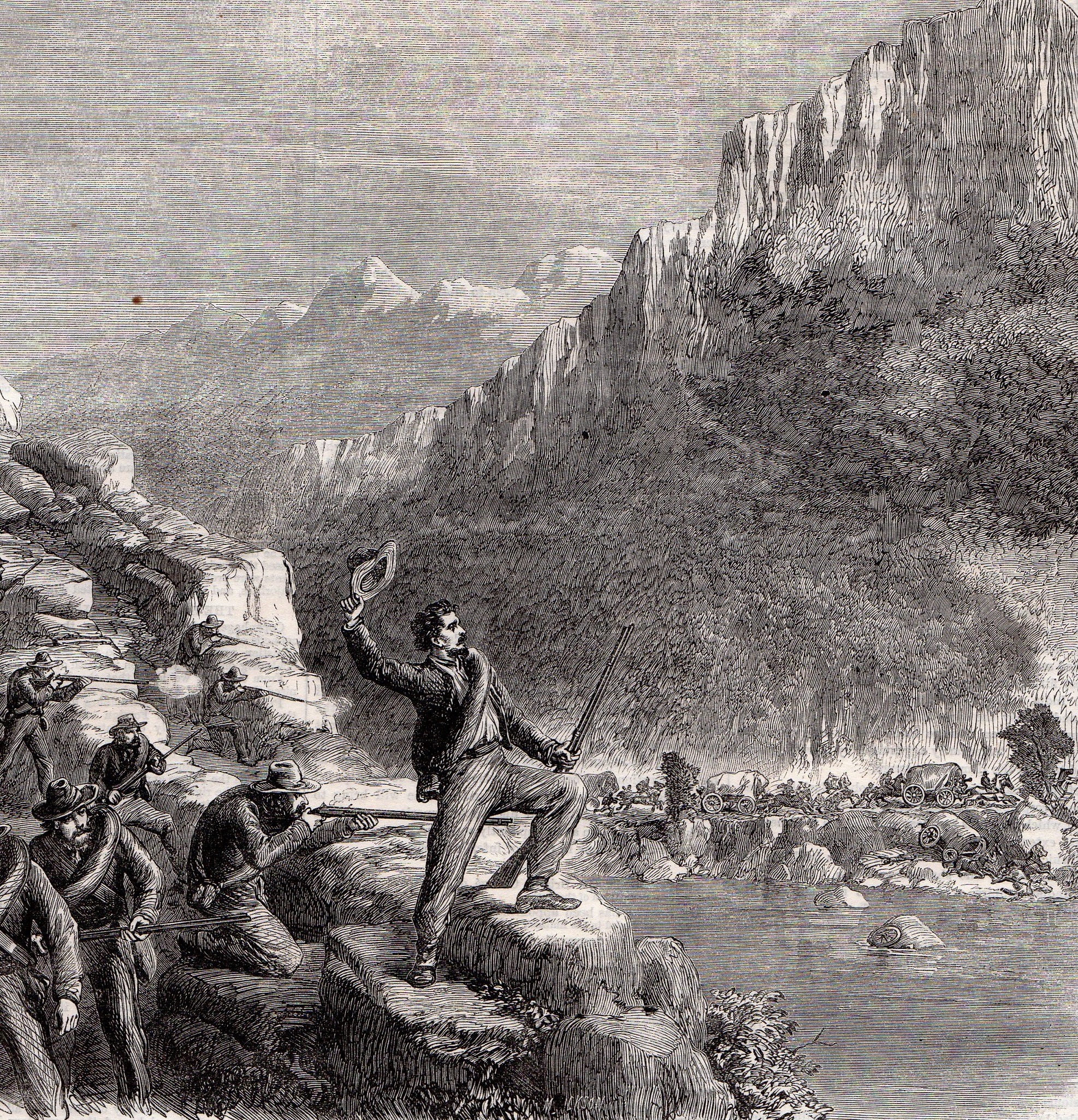

Amongst the large rock outcroppings, the Alabamians watched as the first Union wagon train proceeded along Haley's Trace on the river's opposite side, letting about two miles of wagons expose themselves before opening fire. One Alabamian remembered the teamsters "whistling and cracking their whips in a merry mood, entirely unsuspecting" of the danger that lay 300 yards away.

The Whitworth sharpshooters shot "down the front teams, at which point the road became entirely blocked. We then proceeded in a leisurely manner to use our [Enfield] rifles. The road was too narrow ... for the teams to turn around or escape in any manner, and they were compelled to stand until all were shot down."

For roughly the next three weeks the Alabamians "progressed very well in our isolated retreat, shooting mules to our heart's content and enjoying the sport immensely." They had reduced the Union army to quarter rations and forced them to rely on the alternative supply route, which sometimes took eight days to complete.

On Oct. 27, the fun was ended by the simultaneous arrival of Union troops at Brown's Ferry and another column of reinforcements coming into Lookout Valley from the west. Realizing they were about to be trapped, the Alabamians strapped all of their cooking utensils onto their mule and soon were ready to leave Raccoon Mountain. "From some cause the mule, in the confusion, not placing our utensils on his back to exactly suit his fancy, got away from the man leading him and went braying and kicking down the mountain trail, the boys laughing and yelling and picking up scattered utensils."

Running along the side of Raccoon Mountain, the Alabama boys then crossed through Lookout Valley between the two columns of Union troops to safety on the side of Lookout Mountain.

The mule arrived with only a skillet handle remaining of his cargo. For the boys of the 4th Alabama who had been through the maelstroms of First Manassas, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga, the affair on Raccoon Mountain would be one of war's lighter and more memorable moments.

Dr. Anthony Hodges is vice-president of the Tennessee Civil War Preservation Association. For more visit Chattahistoricalassoc.org or call LaVonne Jolley, 423-886-2090.