Note: This column was updated on Jan. 8 to correct the city in which Mary Lee Rice served on the City Council.

More than a century ago in Chattanooga, prostitution led to prosperity.

A meticulously researched new book reveals that some Chattanooga brothel owners in the early 20th century took in up to $50,000 a year, which is the equivalent of about $1.5 million a year in today's dollars.

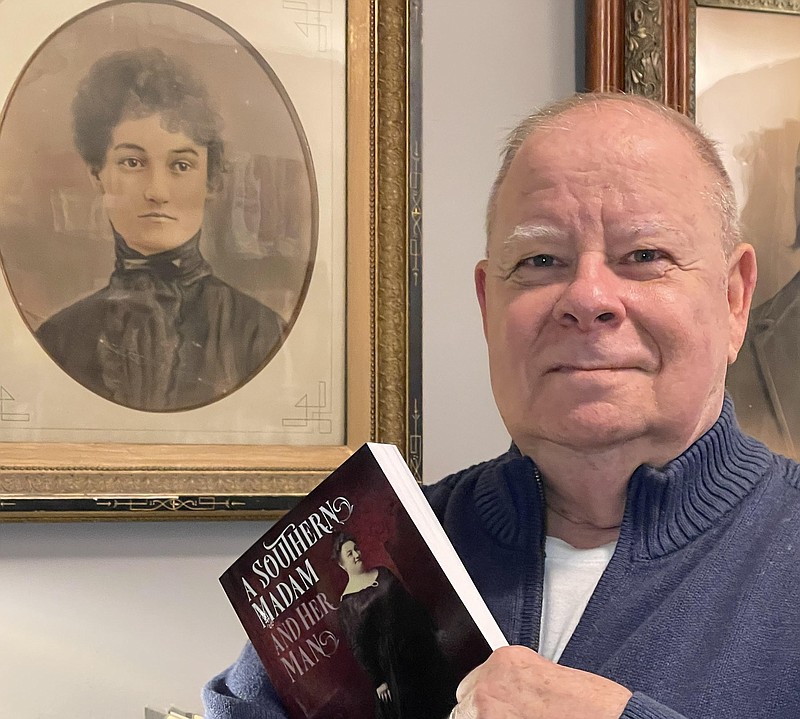

David B. Dearinger, a retired art history professor living in Richmond, Virginia, has spent about a decade researching events surrounding the city's all-but-forgotten "red-light district," which flourished here from the late 19th century until about the start of World War I. Estimates are that there were 15 to 20 brothels concentrated in a few square blocks in West Chattanooga, each housing up to 12 prostitutes.

Dearinger has compiled his research into a book, "A Southern Madam and Her Man" (White Poppy Press, 337 pages, Amazon.com), which is a deeply personal account of the lives of his great-grandparents, Susie Tillett, who ran brothels here and in Lexington, Kentucky, and her common-law husband, Arthur Jack, a saloon owner and sportsman who was frequently mentioned in Chattanooga newspaper stories.

In a humorous aside to his efforts, Dearinger said he visited the graves of his great-grandparents in Lexington before the book was published and "asked" Susie Tillett if she had anything that she wanted to "say" before the book came out.

"About that time, a buckeye fell off a tree and hit me in the head," Dearinger said in a telephone interview.

Using census data, newspaper reports, court records and city directory listings, Dearinger's book paints a picture of a brothel district off West Ninth Street (now M.L. King Boulevard) adjacent to what is now known as the West Village. Some of the streets in the so-called "tenderloin district" no longer exist, having been excavated during urban renewal projects later in the 20th century. The "red light district" was roughly at the present-day location of the U.S. Highway 27 and M.L. King Boulevard interchange.

(READ MORE: West Villiage developers buy boutique motel)

"I started working on family history when I was 14," Dearinger, 73, said, noting that it wasn't until the past decade that he began to piece together the colorful lives of his great-grandparents through digitized newspaper archives. "As far as I know, nobody in my family knew about (Susie Tillett's occupation)."

Dearinger discovered that Susie Tillett fell into prostitution in Lexington, Kentucky, as a young woman after her parents died, and two of her sisters eventually joined her in the profession. She opened her own "parlor house" — the period name for an upscale brothel — and became a madam there. She later opened a house of prostitution in Chattanooga when authorities cracked down on brothels in Kentucky, Dearinger learned, and she continued to run houses in both cities for decades.

In Chattanooga, the city gained a reputation for being somewhat tolerant of the red-light district off West Ninth Street, perhaps reasoning that containing vice to one part of the city made it more manageable.

Susie Tillett's house on Helen Street was considered one of the most opulent parlor houses. It was lavishly furnished and decorated and attracted more affluent customers. It's assumed that some of Tillett's clients were prominent Chattanooga men, which may have accounted for the look-the-other-way attitude displayed by some city officials.

(READ MORE: Westside businesses were sacrificed for urban renewal)

Mary Lee Rice, a professional genealogist who helped Dearinger research his book, said records show a pattern of police indifference to the houses on Helen, Florence and Penelope streets, which made up the red light district.

"The process was for the cops to raid the madams' houses, haul them into court, charge a nominal fee and then leave them alone for six months," Rice said in an interview.

Rice, who used to be on the Vestavia Hills City Council near Birmingham, said authorities a century ago seemed to be much more tolerant of prostitution than they are today.

"The courts didn't treat (prostitutes) harshly," she said. "They didn't get thrown in jail."

In fact, one local judge in the period said he would rather sentence a man to the state penitentiary than to send a woman to the county workhouse. And indeed, there is no record of Susie Tillett ever being incarcerated for any length of time.

In a newspaper account of a police inspection of her house on Helen Street, a reporter described Tillett as wearing "a cloud of white silk and lace. She had her hair powdered and looked for all the world like she was going to a (costume ball)."

While Dearinger was never able to confirm that Susie Tillett and Arthur Jack were ever officially married, they were clearly attached for decades and even adopted a daughter, Gracie, who lived with the couple at their home in Kentucky. She was apparently never aware of her mother's profession.

For his part, Arthur Jack was said to be a dashing figure and sportsman who dabbled in horse racing and roller-skating competitions among other pursuits. At points he owned and operated the Two Jacks Saloon on Ninth Street in Chattanooga and a vaudeville theater in Lexington.

Dearinger said he believes his great-grandfather left a wife and family in Atlanta (but was never divorced) and met Susie Tillett in Chattanooga in the late 1880s, although the exact circumstances of their meeting is not known.

One episode in Arthur Jack's life drew national attention. In 1894, Jack had an entanglement with a Chattanooga woman named Nellie Spencer, whose husband was a grocer. According to news reports, on Feb. 28, 1894, Jack and the married Mrs. Spencer took a "secret" carriage ride into the countryside and were chased down by Nellie's aggrieved husband, Ed Spencer.

During the ensuing confrontation, Jack was shot twice but not mortally wounded. The story was picked up by various regional and national publications, and Jack was momentarily famous.

When he found a press report noting that Susie Tillett comforted Arthur Jack in the hospital after the shooting, it confirmed Dearinger's suspicions that Jack, of Atlanta, and Tillett, of Lexington, were a pair here in the 1890s.

"It was a national scandal," Dearinger said. "I always said as a kid, 'If I ever go to heaven, the one person I'd want to meet first is my great-grandpa.'"

Dearinger said the red light districts in many American cities, including Chattanooga, went away after federal authorities made it clear in the run-up to World War I that the government would not tolerate areas of concentrated prostitution in cities near military bases such as nearby Fort Oglethorpe.

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6645.