Like many young boys, baseball called out to Booker T. Scruggs. He grew up playing ball, he was a member of Jon Engel's Knothole Gang and he even watched live as Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier and wowed the world.

But as a child in the early 1950s, Scruggs didn't look at Robinson as a role model because he was a fellow African-American. As so many reacted to a man of color playing Major League baseball, to a young Scruggs, he was an idol because of his ability. "Race didn't impact me at that time. To me, he was a ball player," Scruggs recalls. "I think that's why, looking back, Jackie Robinson had such an influence on me. I continued to follow him after his career and he became a leader, an African-American hero in my life."

At Chattanooga's historic Engel Stadium, Scruggs and his father would watch from the bleachers. "I think that's when race really struck me as a kid. I liked baseball and wanted to watch, but it was always from the bleachers," Scruggs says of the designated seating at the time.

And when Chattanooga's negro league played exhibition games in the months following the Chattanooga Lookouts' regular season, Scruggs and other African-Americans still sat in the bleachers, uncovered.

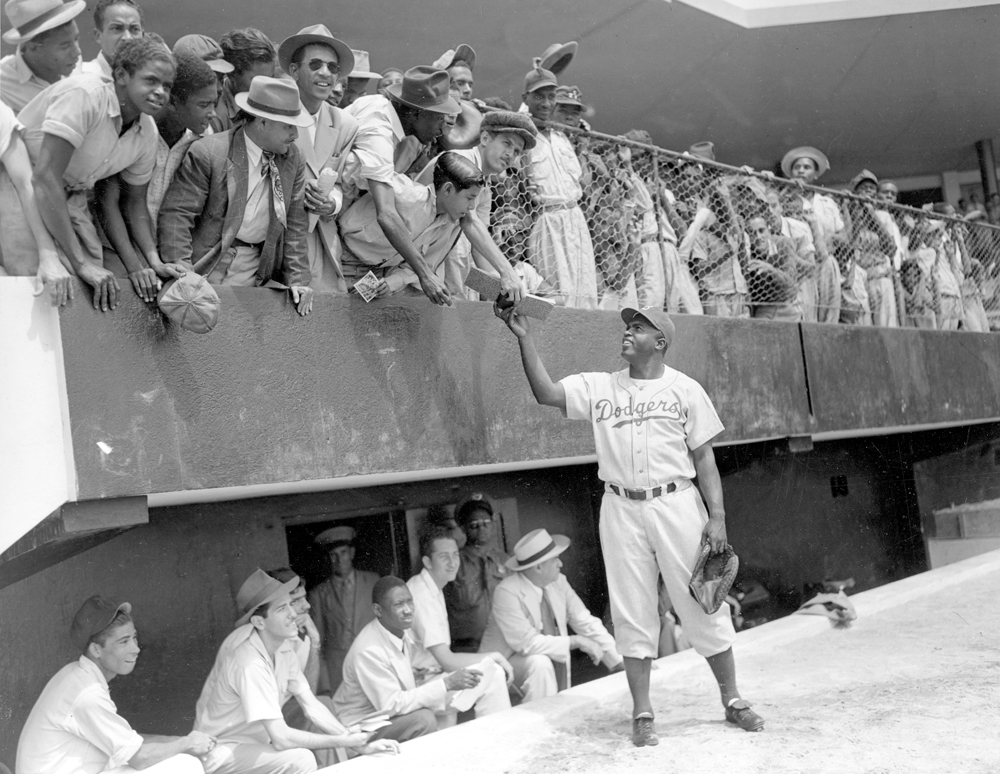

At around the same time, Chattanooga had no choice but to recognize a sign that changes were coming. Baseball hero Jackie Robinson played exhibition games at Engel Stadium with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The game in 1952 was a first for Chattanooga, the first in which whites and black played against each other.

This era of segregation is depicted in the movie 42, about the life of the famed Brooklyn Dodger who broke the color barrier in 1947. Parts of the movie were filmed at Engel Stadium last summer, evoking memories for many of the generations who experienced that era of racial discrimination. The movie brings forward an honest look at a time when an African-American baseball player was not welcome to share a field, let alone a bench, with white players.

The movie debuts in theaters this month.

Revisiting the era of segregation and racial violence is all too familiar to Scruggs. He and his fellow Howard School Class of 1960 started a movement to take Civil Rights out of the bleachers and rushing onto the field.

In February of 1960, when African-Americans were sorted into services, Scruggs' senior class of boys felt a call to make a statement. Whereas they could spend money, their own money they earned as everyone does, at a lunch counter like Kress or Woolworth's, they could not sit and be served; they would have to take theirs to go. "We did this as an act of solidarity, to indicate to Chattanooga that in certain situations people get perks because of the color of their skin," Scruggs says. "We wanted to call attention to these inequities."

Days of demonstration and involvement with opposing whites and police would follow. But Scruggs and his Howard classmates set an example that started a movement in Chattanooga. The act chipped away at an already crumbling façade. Through public outcry, violent racial acts were no longer answered with silence.

Time would move forward and slowly desegregation would continue in Chattanooga and around the Southeast. In the next few years, movie theaters, stores, restaurants and even schools would be open to equality. But for many, the physical desegregation was the only desegregation of its kind.

"The problem is changing the mindset. You can legislate action like desegregation but it takes an ongoing process to change the minds of people," Scruggs says.

In the early 1980s, a movement to honor Martin Luther King Jr. started in many communities throughout the Southeast. Many towns were renaming important streets MLK Boulevard. Likewise, a movement began in Chattanooga to rename 9th Street to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in 1981. The street spans across the heart of the business district. The Read House shares a place on the street, as now does EPB, Krystal and other major business buildings. The street continues to span east, where it comes into a more urban residential area, now abutting the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

The street was also the place of significance to the Civil Rights Movement. Demonstrations, marches and even violence occurred on the corners. But at the time, city officials and prominent white business leaders resisted renaming all of 9th Street. It was only the convergence of both white and African-American pastors and a demonstration where "MLK Blvd." signs were placed across the existing street signs that convinced Chattanooga City Council to make the controversial decision. Today, more than 900 cities in the world have commemorated King with a street.

For University of Tennessee professor Derek Alderman, where the street is located inside the city can show a lot about racial progress. Through his research about MLK boulevards and streets all over the world, he's seen how they fit into history. "In Chattanooga's case, major leaders wanted to only change part of 9th Street. Historically there are a lot of politics and control involved in these decisions," Alderman explains.

The vocal response and continued effort to rename all of 9th Street can be an indicator of how far the area has come. Alderman says it was an impressive display that reminded people of the Civil Rights Movement. But it was also the support of local white pastors that put the pressure on City Council to make the right decision, and completely rename the street in January of 1982. "Chattanooga was monumental, and it was important that the movement to rename was completely successful," Alderman says. "It exposed a central tension, and like many other cities, the problem revolves around the place. Where do we put it?"

Today, Chattanooga's ML King Boulevard tells two different stories. There is still a prominent business district, but east of Georgia Avenue bordering UTC, the street is undergoing changes.

"I wanted to move into the city and build a house and have an impact on the MLK area," says Moses Freeman, now the president of the MLK Neighborhood Association. "I became a developer and built houses in the neighborhood." Freeman says he came into an area that was deteriorating and where crime and drugs were present. He could see a movement through other longtime homeowners and wanted to join the association to help take back the neighborhood and enhance what others had done.

"We wanted to show diversity and move the neighborhood in the way that Dr. King would be proud of," Freeman says. "We have ownership of the neighborhood and we all come together and have mutual respect for each other." Bringing an old and once troubled neighborhood back is not without its challenges, Freeman says. People moved out of the area, leaving empty homes and businesses behind. "There are businesses that have closed, restaurants, night clubs and many centrally African-American businesses that left, and we're working to bring some back and rejuvenate the area. To me, it's one of the more desirable locations to live in the city."

Now the neighborhoods and existing businesses are working hard to bring activity to the area. The neighborhood isn't known for crime and drugs as it used to be, but there are still areas in decline. "Some businesses like Champy's have found success," Freeman says. "But it's going to take all races to get the business district back... we're trying to attract people with newly constructed buildings and rebranding."

While ML King Boulevard and other neighborhoods in the city go through changes and growth, Freeman is still soothed by how far the area has come. "Chattanooga has always struggled... we were a typical Southern city," Freeman describes. "If not for federal law, it wouldn't have changed. It was the insistence of young African-Americans that changed this."

Now as a professor of Sociology at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, a school he once was barred from attending, Scruggs is also pleased with how far the region has come. Seeing an African-American president win a second term shows just how far prejudice is gone from the minds of the American people. "Just that I'm able to be at UTC for 40-plus years is a big deal," Scruggs says. "I would pass by UTC every day to go to school and I wanted go there but couldn't. Now I'm here."

That reflection is a sentiment shared by many who demonstrated and lived through the Civil Rights Movement. After King watched Robinson break the color barrier as a teenager, he would continue to praise Robinson and recognize his role in integration. At the end of his career, Robinson was warned against speaking about the Civil Rights Movement, as it could affect his legacy. But King referred to Robinson as "a pilgrim walking the lonesome byways toward the high road of Freedom. He was a sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before the Freedom Rides."

Scruggs and his generation were also warned against speaking out. But as changes happened, and integration continued, the once controversial actions were vindicated.

That's not to say Scruggs thinks that progress should stop. He'd like to see more African-Americans in faculty positions at UTC and other universities and colleges, and in supervisory and administrative positions.

"It's always a concern here for me," Scruggs says. "There's always more steps to take."