Aquaponics Fast Facts

» Aquaponics is known as a "closed loop system," meaning everything is recycled - even waste. » Fish waste fertilizes the plants and the plants' roots purify the water to return to the fish. » Aquaponics uses 90 percent less water than traditional soil farms and a fraction of the electricity. In fact, several HATponics systems are powered by sun and wind.» When using aquaponics, you can produce as much food on 1/3 of an acre than you can on 10 acres with traditional farming, Cox says.

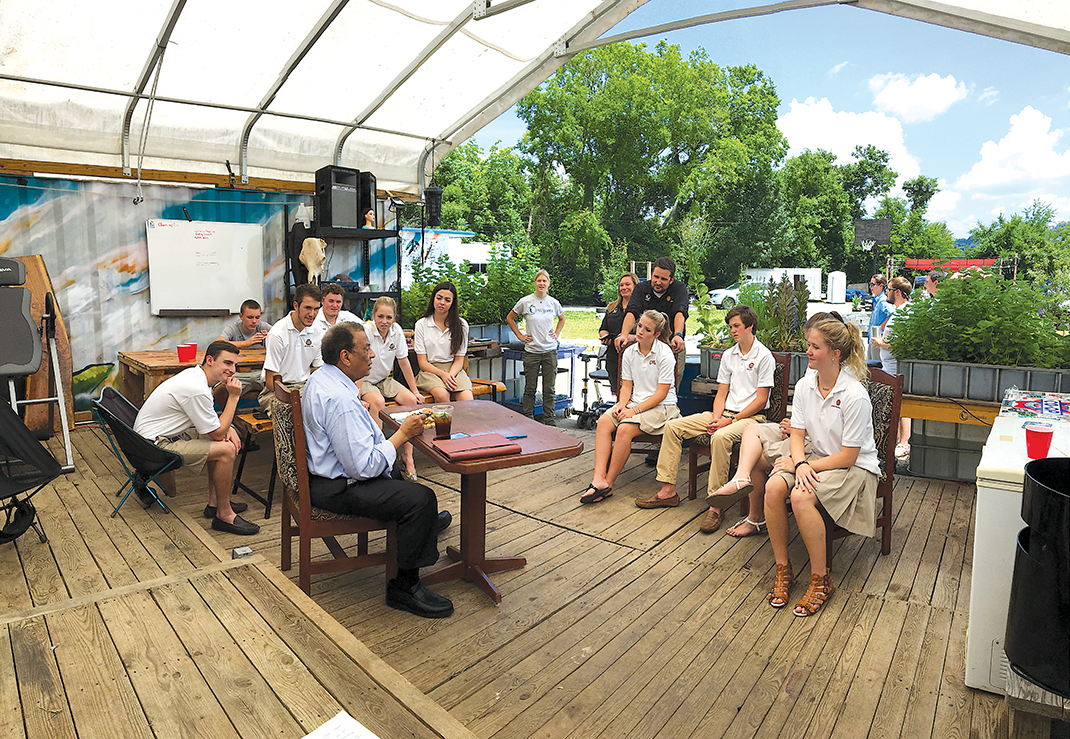

It was a hot June afternoon at HATponics, an aquaponics farm in Rossville, Georgia. Ambassador Andrew Young looked at the plate of food set before him: blackened catfish and a green salad prepared from food harvested just 25 yards from his seat in the shade.

"Hey y'all, we prayin'!" he called to the group.

Even though Young, 85, is a former Atlanta mayor, the first African-American appointed ambassador to the United Nations, and a prominent Civil Rights leader, he's never far from his roots as a minister in a Southern farming community. In fact, his agrarian background is what ultimately led him to HATponics, which he has partnered with on several sustainable agriculture projects through his namesake nonprofit, The Andrew J. Young Foundation.

"Ryan is one of the brightest and most decent people I've met," Young says of HATponics CEO and founder Ryan Cox. "He's a disciplined scholar and a brilliant guy. I think it's just a matter of time before this catches hold and becomes a worldwide effort."

To help spread that word, Young's foundation arranged a private tour of the Rossville farm for 12 of his personal contacts - dignitaries from Africa, Haiti, Jamaica and the U.S. Students from Dalton's Christian Heritage School and Chattanooga Girls Leadership Academy were also invited to share their upcoming projects through HAT-Academy, HATponics' international STEM immersion program.After the hour-long tour, Young sat in the shade with the teenagers as if old friends. He shared anecdotes from his time as personal confidante to Martin Luther King Jr., and asked them about their intended majors.

As Christian Heritage senior Meghan Higgins talked about the bridge she and her classmates will build in Haiti next summer, Young reminisced about a similar experience he had almost 70 years earlier in post-WWII Germany.

"I am who I am in part because I went to Germany and Austria to work in refugee camps right out of college," he says. "It changes your life. It's hard to describe the value of that kind of experience. The world would be so much better off if all of Congress were required to do a trip like these kids."

Located on a small plot behind an abandoned high school, HATponics has installed custom-built systems in 20 countries and five continents since beginning in 2013. Not only have they created the world's first portable farm, they can monitor and turn that system on and off with a smartphone.

But the business's projects in over 1,000 schools worldwide are often what excite Cox the most.

"What we offer the world from HATponics is the ability to sustain itself, and teaching future generations is one of the basic building blocks," he says. "We can create commercial entities or build corporations, but the truth is, if we don't change the mindset of our children, we don't have a chance for tomorrow."

The HATponics team has installed aquaponics systems in schools up and down the Eastern Seaboard, offering hands-on STEM learning opportunities. They've created a "food tunnel" in a school lobby and re-created a lake habitat inside a classroom.

Cox has personally visited many of these schools to do presentations or teach classes, but things really got interesting in 2015, when he started giving high school juniors and seniors real-world problems to solve.

"Kids are capable of way more than we ask of them," he says. "It never ceases to amaze me what they can accomplish when appropriately challenged and supported."

Far beyond a typical class project, the students were essentially contracted by HATponics. If their designs didn't work, they didn't travel. Even once proof of concept was established, the kids had to secure the materials needed, whether that meant procuring on-site or dealing with customs. And they had to raise money for all of their expenses, which often meant making presentations to corporate sponsors.

"In all of these projects my primary job is driving the van," laughs David McVicker, high school principal and physics teacher at Christian Heritage. "We hold them accountable, but they are taking on the lion's share of responsibility."

McVicker chaperoned Christian Heritage's past two trips and is currently helping coordinate their 2018 trip to Haiti along with the HATponics team. There, students will build a 100-foot bridge across a river that floods during heavy rains, cutting a nearby village off from schools and churches.

Juniors and seniors will engineer and build the bridge with minimal input from HATponics and a few professional engineers to check their work.

"These trips are an opportunity to see what they can do if we get out of the way," McVicker says. "I love the idea of taking teenagers and showing them they can have an impact on the world they don't have to wait until they're 40."

You might be hard pressed to find many 40-year-olds actually willing to undertake this trip. The bridge will only be about five feet off the ground, but it rests at the bottom of a canyon that's prone to flash flooding and rock slides. Once the pilings are set, the students will construct a zipline across so that every student will be connected by harness while working.

On the day of Young's local HATponics tour, the students met several contacts who offered personal help, such as a businessman who said he can help source local materials. The General of Haiti has offered help through customs - which is notorious for requiring bribery from foreigners - and Higgins met the Ambassador of Haiti, who also offered his personal help."It was incredible how I am talking to these people and they're actually listening to what I'm saying," the Christian Heritage senior recalls. "After talking I felt like they had developed a certain amount of respect for us, and that was really cool to experience."

If preparing for the trip is hard work, it pales in comparison to what awaits when the students arrive. They usually have less than two weeks to complete their projects, often spending 10-hour days in extreme heat doing manual labor.

Cleveland High School recently sent four students to the Jamaica Christian School for the Deaf in Eden to build a prototype of an aquaponics system so students could recreate it for use in their homes. The systems can offer sustenance and income opportunities to Jamaica's deaf population, whose outlook is often bleak due to few job opportunities and little government assistance.

They had 10 days to take the system from concept to final product using only locally sourced materials and tools. Bamboo replaced PVC pipe, which then had to be cut with machetes or handsaws to precise measurements. Twine was used instead of bolts. The only purchased items were a $40 water pump and a barrel for the fish.

"I had a basic idea of aquaponics but was completely oblivious to all the types of systems until I got down there," says Matthew Hattabaugh, a 19-year-old CHS alum now studying civil engineering at UTC. "Whenever we asked a question, Ryan would tell us to put our heads together and figure it out. But if I were to go back tomorrow, I could rebuild the whole system easily."

One of the biggest benefits of HATponics and STEM learning is teaching students how failure is part of the process. Designs are often scrapped and prototypes abandoned. And sometimes, trips don't happen. The students from CGLA fell short of their $30,000 fundraising goal and had to cancel their July trip to Honduras. The girls are part of the YMCA's after-school program called Project Design Build. With the help of HATponics they build and sell systems to elementary schools, preschools, after-school programs and nonprofits. The mission trip to Honduras with HATponics was how they'd voted to use their profits.

"It's not unusual for students to learn that lesson the hard way," says Bill Rush, executive director of James A. Henry YMCA, in regards to the girls' failed summer trip. "But all it did was inspire them more. We don't look at things as failures, but opportunities to take a different course of action."

"One of the biggest benefits of these partnerships is allowing students to design for a person rather than just a grade," says Cleveland engineering teacher Ben Williams. "They're not just trying to prove they know stuff, they're proving they can help person A in location A. Very different things happen in a classroom when you have that, such as empathy or character development."

HAT-ACADEMY IN ACTION

A highlight of HATponics' international mission trips

WIND TURBINE, SWAZILAND, AFRICA

Christian Heritage School

Students designed and built vertical-axis wind turbines, which power pumps for a commercial-sized aquaponics system recognized by the United Nations Environmental Program. The system they helped power now serves as a platform to train 1,500 farmers across the region most heavily affected by drought.

GROW DOME, KISALAYA, NICARAGUA

Cleveland High School

These students designed and built a 19-by-12-foot grow dome that acts as a seed-starting greenhouse supplying 1,500 residents. The entire design was broken down into a backpack so students could hike it into the remote village for installation.

SOLAR ARRAY, EDEN, JAMAICA

Christian Heritage School

Using only hand tools, students dug out rock on a mountainside to build terraced beds for a system they helped construct out of local materials and steel frames, built on-site by HATponics' chief fabricator. Once complete, the students engineered battery and solar components to power the system, all benefiting the Jamaica Christian School for the Deaf.

RESIDENTIAL AQUAPONICS SYSTEM, EDEN, JAMAICA

Cleveland High School

In just 10 days, students designed, prototyped and built an aquaponics system for at-home use, made exclusively with local materials and tools. Local deaf students helped in the final stages so they could learn to replicate the system for personal use.

SUSPENSION BRIDGE, HAITI

Christian Heritage School

In the summer of 2018, students will construct a 100-foot steel-and-wood suspension bridge over a flood-prone river that severs villagers from schools and churches during heavy rains. The bridge is an important first step to allow for a sustainable school and farm HATponics has planned for the future.

For more information on each school's project, visit hatponics.com/hat-academy.