Chattanooga: A ‘trail town’

In 2013, Mayor Andy Berke named Chattanooga the Great Eastern Trail’s first official trail town, making it the largest city in the country to host a long-distance trail. Trail towns become important destinations, both for thru-hikers who need to resupply and tourists who seek weekend adventure. This form of niche tourism also tends to attract new businesses — from outdoor outfitters to hiker-friendly hostels to local eateries.

On a recent Saturday morning, I filled my backpack with fruit and protein bars and headed out to Cloudland Connector Trail, a 14-mile footpath from Cloudland Canyon State Park to Lookout Mountain.

The Cloudland Connector Trail is also one section of the Great Eastern Trail, America's newest long-distance hiking path which will stretch 1,800 miles from Alabama to New York when finished. Tom Johnson, president of the Great Eastern Trail Association, estimates the GET is 70 percent complete, though it has already been thru-hiked by a few ambitious hikers who didn't mind road-walking its unfinished sections.

I wanted to walk a mile - or 14 - in those thru-hikers' shoes. So, dressed in layers and equipped with snacks, I embarked on my longest day-hike to date.

The GET is being touted as a wilder, quieter alternative to the Appalachian Trail, and on my section, I found this to be true. The forest was silent save for the creak of winter trees and the crunch of my boots on frozen ground. When a pileated woodpecker squawked overhead, I gasped in surprise.

I was nervous.

Each mile, I realized, moved me farther away from the preoccupations I'd come to depend on: text messages; traffic; to-do-lists. On the trail, I had one purpose: to keep walking.

As the sun climbed higher into the blue sky, my anxiety began to subside - along with my need for distractions.

Between the sweetgums and rhododendron, I let my mind wander. I thought of nothing and everything. By mile 10, I was singing with the birds. I felt like I was born to put one foot in front of the other, and, I suppose, I was. That urge to walk great distances is prehistoric.

As a concept, the GET is that simple. But as a project - one that involves nine states, 20 trail organizations and countless committees - it is more complex.

Sixty-five years ago, the GET was proposed by Earl Shaffer, who, in 1948, was the first person to thru-hike the AT.

Shaffer's idea was to link the existing trails that ran parallel to the AT. Over the next couple of decades, his proposed path became known as the Western Appalachian Alternative, or the WAA. Trail organizations such as Potomac Appalachian Trail Club, headquartered in Virginia, and the Southeast Foot Trails Coalition, headquartered in North Carolina, began to work together to plan the WAA, and somewhere along the way, it was renamed the Great Eastern Trail, or the GET.

In 2007, the Great Eastern Trail Association was created to plan, build and manage the GET. The GETA is comprised of representatives from 11 regional trail groups ranging from the Alabama Trails Association to New York's Finger Lakes Trail Conference. Each regional partner is responsible for managing the section of the trail that runs through its state. For instance, the Cumberland Trails Conference manages the Tennessee segment with help from the American Hiking Society and Southeastern Foot Trails Coalition, two organizations that help support the GET but do not belong to the GETA.

President of the GETA Tom Johnson describes the GET as "very decentralized in terms of management." In contrast, the AT is cooperatively managed by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service.

The difference in the way these two trail systems are managed might best be illustrated by their blazes, the colored markers found on trees, posts or rocks to indicate the route. The AT is marked entirely with white blazes. But the GET is marked with different colors, depending on each established trail's own preference. The Cloudland Connector Trail, for example, features green blazes. The Cumberland Trail features brown blazes.

Members of the GETA meet only once per year.

"When we get together, it's just to update each other on what's going on with our own segments," Johnson says.

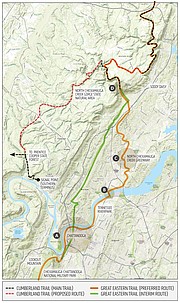

The Chattanooga segment will span 26 miles, from the Georgia-Tennessee state line on Lookout Mountain, through downtown, to Soddy-Daisy. The focus for this local stretch is to complete the few missing links to connect Cloudland Connector Trail to the Cumberland Trailhead in Soddy-Daisy.

The Chattanooga Segment

Traveling north from Georgia, the Clouldland Connector Trail currently ends along Nick-a-jack Road. From there, it is 1.5-mile road walk to Lula Lake Land Trust, where, in December, crews began construction on a 2.9-mile connector trail that will link Lula Lake's trails to Convenant College's trails – which take hikers into Tennessee.

Then, the GET picks up on Lookout Mountain's National Park Service trail at Point Park, continues on the Guild-Hardy trail, then travels down into St. Elmo on the southside of Chattanooga.

The first missing link in the Chattanooga segment is a path to connect St. Elmo to the southern end of the Tennessee Riverwalk, which begins on Middle Street in the South Broad District. The city has already assured work to connect these two points, says Linda Hixon, chairperson of GET: Chattanooga, the committee of the Cumberland Trails Conference tasked with planning and building the local stretch of the GET.

The GET then follows the Tennessee Riverwalk all the way to the C.B. Robinson Bridge, which carries Dupont Parkway. The second missing link is the crossing of that bridge. The challenge, says Hixon, is to make that bridge more pedestrian-friendly – an issue being examined by the Tennessee Department of Transportation.

Once across the bridge, the GET travels along the northside of the river to the Chickamauga Dam, then to the North Chickamauga Greenway. The largest missing link in the Chattanooga segment is the stretch between the North Chickamauga Greenway and the Cumberland Trail.

A sub-committee of GET: Chattanooga responsible for that specific segment has identified a preliminary path, Hixon says. But she adds, "We still have to have conversations with property owners and find out their level of interest."

From Soddy Daisy, the GET travels along the Cumberland Trail for 245 miles.

Robert Weber, chairperson of the Cumberland Trails Conference, says the CT is about 90 percent complete, taking hikers from Signal Mountain to the Tennessee-Kentucky state line. But, naturally, it, too, has already been thru-hiked by a few ambitious hikers.

Balancing Recreation and Conservation

Eventually, the CT will stretch over 300 miles along the eastern edge of the Cumberland Plateau. Currently, about 200 of those miles are open for hiking - though that may depend on how one defines "hiking."

According to Chris Pickering, who thru-hiked the CT with Ethan Alexander in 2016, many of those miles were more akin to bushwhacking. That's because parts of the trail do not see enough traffic to require upkeep, says Pickering, an art student at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and a veteran of long-distance trails.

In addition to the CT, Pickering has thru-hiked the 2,200-mile AT and 1,600 miles of the 2,600-mile Pacific Crest Trail which traces the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains.

The AT and PCT are two of the most popular distance trails in the world. Between the two, the estimated number of annual visitors ranges from 100,000 to over a million.

"The AT and the PCT are nice social experiences," Pickering says.

But inevitably, all that traffic leaves an imprint on the landscape. According to a 2003 report published by the Appalachian Trails Conference, three of the biggest problems along the AT are litter, human waste and erosion, problems compounded by hikers who do not follow the rules.

For instance, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy promotes leave-no-trace ethics, meaning what is packed in should be packed out. Human waste should be buried in an 8-by-6-inch "cat-hole" located at least 80 steps away from campsites, water sources or shelters. Tents should be pitched on the already-impacted areas of campsites, and hikers should never shortcut switchbacks, which causes the loss of ground cover, damage to tree roots and erosion.

Some of these issues have become so serious along the AT's northernmost 15 miles that Baxter State Park officials are threatening to reroute the trail off Mount Katahdin, Maine's highest peak and the grand finale for northbound thru-hikers.

"It was frustrating seeing people [on the AT] who have barely hiked before. They bring like 70 pounds worth of stuff and have no idea how to be responsible in the woods," Pickering says. But, he adds, long-distance hikes are a great way to teach a person about sustainable living.

In the 1940s, the decade when Earl Shaffer, grandfather of the GET, first thru-hiked the AT, a total of three people made that trek. Since 2010, 4,019 people have thru-hiked the AT.

What makes the AT and the PCT special, Pickering says, is that they are community-driven. But what will make the GET special, he says, is its feeling of undisturbed wildness.

That chilly morning, as I trudged along my 14-mile section of the GET, I found a stillness so profound it was broken only by the squawk of that woodpecker; a wild, prehistoric sound that shook the treetops. But with each step I took, the sound faded until becoming just an echo, and the forest returned to silence.

The GET's first thru-hikers

On Jan. 9, 2013, Jo "Somebody" Swanson and Bart "Hillbilly" Houck embarked on an 1,800-mile walk from Alabama to New York. Six months and 10 days later, they became the GET's first thru-hikers. Along the way, they blogged about their journey, which, of course, had its highs and lows. Here are a few excerpts from their blog about their journey through the Chattanooga area.

"Georgia magic"

» posted January 28, 2013

What an unexpected day!

We awoke with the dream of another 20-mile day. A few miles into the day, my ankle voiced its extreme displeasure with that plan. We hiked 10 miles to Lyerly and 4 miles down the road, my ankle was sending me a message that cannot be repeated in a public forum. I sat down in the grass, in pain and stressed about where we could [spend] the night. (roadwalks are tricky)

Then like magic Ramar showed up, who invited us to stay in his yard. He brought me an epsom salt bath and kept us company. Then Angie came home and she cooked us huge hamburgers! It was an absolutely magical evening with them and their stories. We have so much new brain candy floating around in our heads. Thank you for being our trail angels!

Thanks to extra rest and care, my ankle is much better and I am cautiously optimistic that we can make it to Chattanooga on Friday. We did 14.5 miles today.

Thank you Ramar and Angie (and Dixie Dog)!

"Sick in Chattanooga"

» posted Feb. 3, 2013

Lots of amazing happenings in Chattanooga, but I am stuck in bed with some kind of illness. I will spare you the details. (Trust me, you're welcome.) Updates coming when I have recovered a bit. -Jo

"Thank you, Chattanooga"

» posted Feb. 6, 2013

What I love most about hiking isn't the trees or waterfalls or scenic vistas. It's not getting into town and eating too much ice cream. It's not the feeling of satisfaction after an 18-mile day, or the feeling of getting the tent set up five minutes before it starts to rain. I love all of that, but the very best part of hiking for me is that every time I go on a long hike, I have my faith in humanity restored.

It seems like everywhere we've hiked, Bart and I have encountered wonderful people who ease our journey and give more of themselves than we can believe. Chattanooga went above and beyond...

...I cannot thank Richie & Shannon and family enough for their hospitality here in Chattanooga. ...It's no fun being sick like I was, but if I had to be sick, I'm so grateful I was with you guys. ...I swear, I'm not always that much of a punk. Bart and I have felt so welcomed here. We really did plan on hiking out today now that I feel halfway human, but it is 11:30 already. We'll see what happens.

Thank you, Chattanooga!

"What a day"

» posted Feb. 8, 2013

What can I say about our first day on the Cumberland Trail? Bart's suggestions:

» we're alive

» Jo's slow

» Jo complains too much (I do not!)

» believe it or not, the rivers are cold in February!

» my kneeeee

» my Gregorian chants through the canyons are much appreciated

» Ali should bring up a 17 pound rock

» at least we have yogurt-covered pretzels.