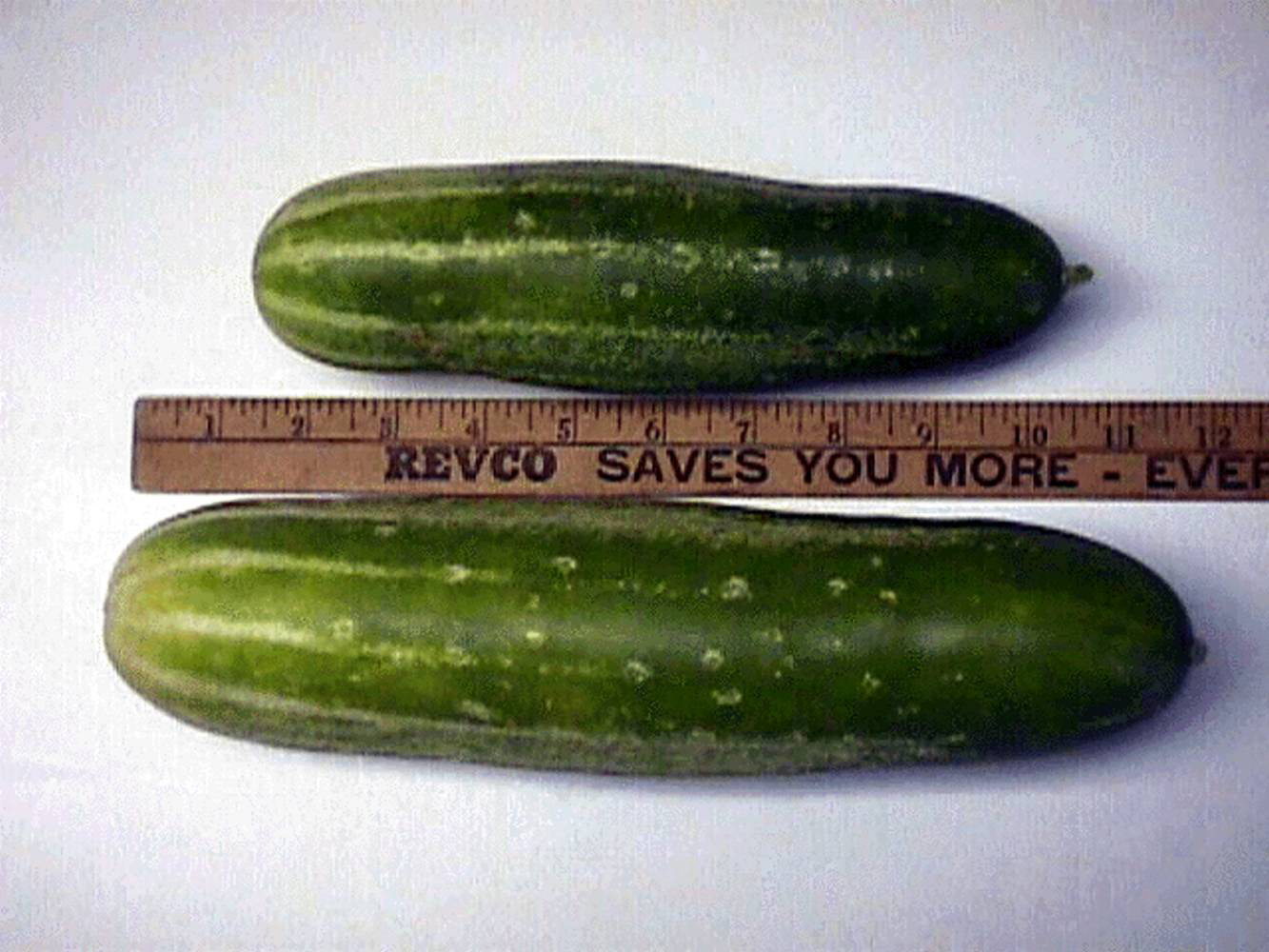

Eggplants the size of footballs. Spinach with leaves so broad they dwarf a grown man's hand. Tomato plants that tower to the height of a two-story house. Pumpkins that pack on pounds faster than a couch potato.

To most gardeners, these probably sound like Big Veggie Tales, if not outright fibs. In a book released last December, however, green thumb inventor Jon Dewey of McMinn County details a series of techniques he says can help backyard gardeners grow vegetables by the bushel with a minimum of fuss.

"This method I'm trying to teach people is designed to grow the most food possible in the smallest amount of space possible with the least amount of work," Dewey says. "I figured out several years ago that plants need vitamins and minerals just like people do. If you give them the right ones, they'll grow huge and you'll get lots of vegetables, too."

"The 20 Foot Tomato Plant: How to Grow More Vegetables Than You Ever Imagined Using the Waterstick Grow System" ($7.69, Amazon), is now available as an e-book. The book provides step-by-step instructions for building the Waterstick, Dewey's patented device that delivers water directly to a plant's roots through a feed tube buried in the soil.

This method, he says, allows gardeners to use one-quarter as much water and grow roots that are bigger and spread deeper. In the book, he also provides instructions for mixing his fertilizer blend, which he calls Super42Vitalizer, and for making Bug Juice, an organic insect repellent. Both the repellent and the fertilizer can be delivered to the plants' via the Waterstick.

In a compact, 12-by-4-foot, raised-bed garden next to his home in Etowah, Tenn., Dewey, 54, has used his gardening system to grow such a profusion of vegetables that he and his wife, Theresa, almost never have to visit the grocery's produce section most of the year.

In the course of three plantings in 2013, Dewey's garden yielded 287 pounds of Better Boy tomatoes, 169 pounds of cherry tomatoes, 184 pounds of bell peppers and so many pounds of acorn squash, sugar snap peas and potatoes, he says he didn't even bother keeping count.

"If you see the size of these things, they were just massive; everything was massive," he says.

Hamilton County Extension Agent Tom Stebbins says one of the main benefits of Dewey's system could be its ability to curtail over-fertilization by focusing the food where the plant needs it.

"By fertilizing at the root level and keeping it in a container, it's not getting away, so the roots will extend in the water and take up fertilizer," Tom Stebbins. "If you're in a more urban environment where you'd like to be careful about over-fertilizing, that's a plus."

Dewey's book is named in honor of what he calls his greatest gardening success story, a tomato plant that grew 20 feet 8 inches tall in 1995. The plant yielded 372 pounds of tomatoes in a seven-month growing season, he says. It was so colossal, he couldn't reach the topmost branches, even when standing on top of a 10-foot stepladder placed on boards laid across the bed of his pickup truck.

Eventually, the massive plant toppled in the high winds brought by Hurricane Opal. When they dug it up, he says, the combined weight of so many tomatoes had bent the galvanized steel pole he'd used to support it.

"When it died I was sad but, at the same time, I was relieved because I wasn't going to have to get back up on that ladder," Dewey admits, chuckling. "It wasn't the safest thing in the world."

Despite his mad-scientist-like enthusiasm for growing enormous vegetables, Dewey says the experience of climbing that rickety ladder taught him to check his "bigger is better" mentality. He now limits himself to growing tomato plants that top out at "only" 12 feet, but he says he's still a compulsive inventor and tinkerer, a skill set he developed as a necessity growing up on a small farm in rural Pennsylvania.

"When you're raised on a farm, you get used to inventing things because things break and you have to come up with ways to make them work," he says. "I'm always trying to invent things. It never stops. Once I get an idea in my head, it won't go away until I do it."

The irresistible itch to experiment has given birth to more than just the Waterstick. Dewey also has developed a number of hybrid vegetables, including "bowling ball" acorn squash and garlic spinach. Techniques for growing these cross-breeds are included in the book in a chapter titled "Fun Experiments."

"I get bored and try and think of things," Dewey says, his voice betraying an impish enthusiasm. "One year, I crossed jalapenos with tomatoes just to see what would happen. They're interesting to grow and fun to mess with your friends' minds."

When Dewey first developed the Waterstick in 1995, the invention attracted the attention of an investor in Gulfport, Miss., who paid $35,000 in 1999 to produce a mold and begin manufacturing it. The device was only available for a few months, however, before Dewey suffered a work injury that left him with five herniated spinal discs. The Waterstick mold sat on the backburner at the Gulfport factory for several years until 2005 when, Dewey was physically able to begin promoting it again.

Then Mother Nature threw a wrench in the works.

"Hurricane Katrina finished the job by destroying the factory where our mold was," he says, laughing ruefully. "That was the end of it."

For several years, Dewey says, he felt sorry for himself at this lost opportunity to sell his inventions. Two years ago, however, he decided he would rather share his secret to bounteous produce, even if it meant losing out on profits from mass manufacturing then device. Even a mad scientist wants to leave behind a legacy.

"Everything in my book works," Dewey says. "We don't have any children, so I don't have anyone to leave this to. I don't want all my ideas and inventions to go away when I'm gone.

"I want people to be able to use them. That's one of the reasons I invented them."

Contact Casey Phillips at cphillips@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6205. Follow him on Twitter at @PhillipsCTFP.