D.R. Fraley says he was blindsided when his daughter's teacher was removed from her public school classroom. Administrators couldn't provide answers. His daughter, who thrives on consistency, regressed so much and became so agitated that he pulled her out of school.

His pain was joined by disappointment as he was unable to reach the man with absolute power over the school system.

For weeks, he begged county commissioners to put him in contact with Superintendent Rick Smith.

There was little they or state legislators could do, Fraley was told.

But Fraley and Smith spoke last week. More than once. For hours.

In the month since Fraley's public appeal, dozens of parents have come forward to commissioners and media outlets with stories about the education and treatment of their children -- some of the school system's most vulnerable students.

Fraley said he has noticed a few common threads, including communication issues, tough-to-reach decision-makers and trouble getting certain services.

While some complaints have been as serious as to allege abuse, advocate Kim Hayes said communication is likely the root of many of the problems.

Hayes taught special education in Hamilton County for three decades. And any issues she ever had with parents, she said, were usually resolved at the building level, not central office.

She said parents feel voiceless. And sometimes programming decisions are driven by money, not always what's best for each individual student.

"They don't have to provide the best. The law says they have to provide an appropriate program for each kid. It doesn't say they have to provide the best program," Hayes said. "I think sometimes the spirit of the law and the letter of the law are misused."

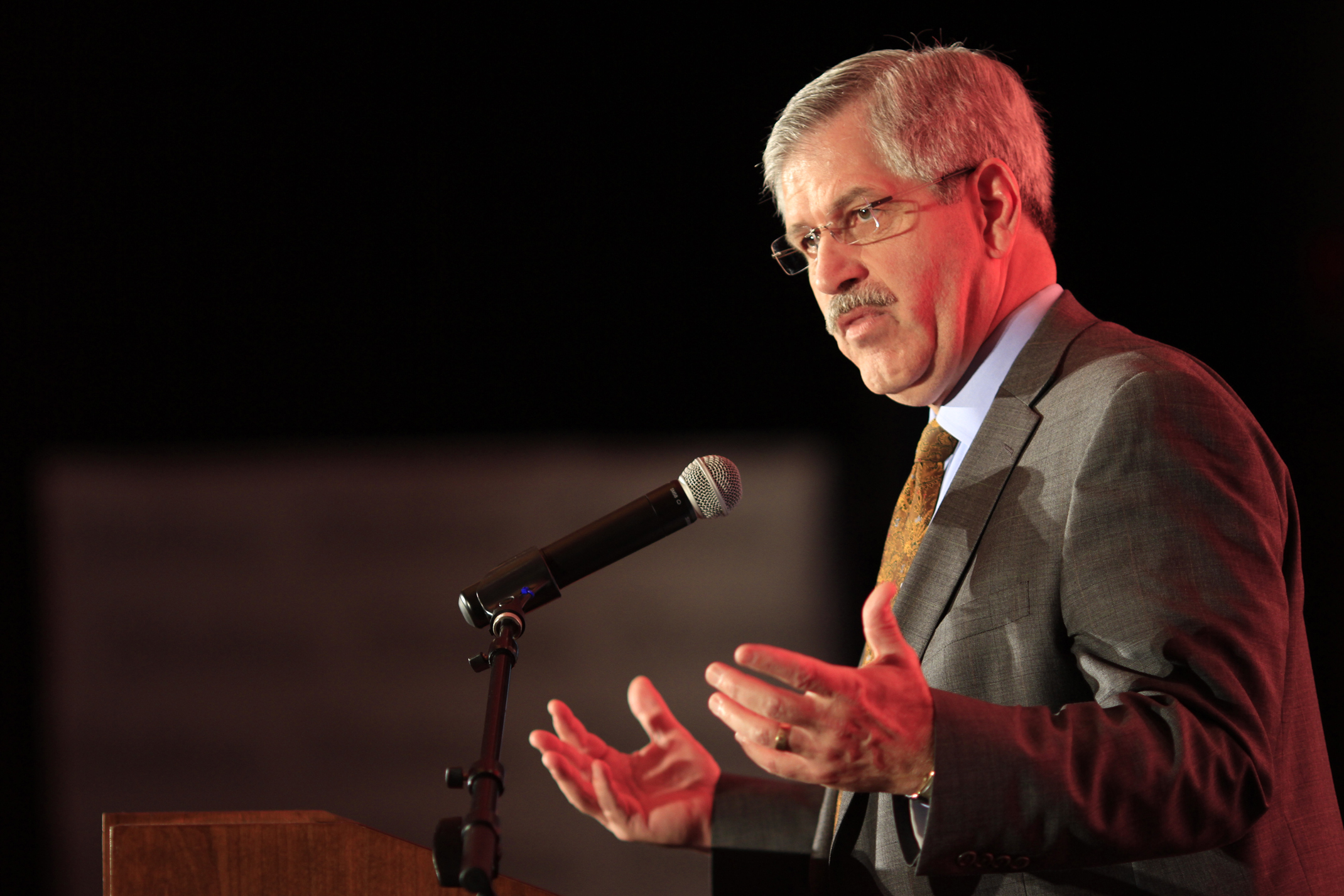

Smith and Fraley still disagree on some issues. The superintendent says, for example, that he "absolutely disagreed" with the parents' public showing at the courthouse and that he stands by the district's special education staff.

But for the first time in weeks, Fraley is optimistic, and said he believes other special education parents have reason to be as well.

The superintendent has looked into Fraley's particular problem and says he plans to review the cases of any other parents who contact him.

But Fraley's hope is grounded in something more fundamental than that:

Smith has been in his shoes.

•••

Key players in the central office say they plan to review the cases of parents who voice concerns. In response to some parents' concerns, Smith said the district made a personnel change at the school Fraley's daughter attends.

But district officials insist that the special education department is providing appropriate services and education to the thousands of students with special needs. And Smith said he sees no evidence of widespread problems within that department.

In fact, the district is providing more special education services and programs than ever before, said Special Education Director Margaret Abernathy. More students are graduating with regular education diplomas and more are going on to find competitive employment, she said.

She said the special education experience is generally very positive for families, which is why the sudden uproar at the county courthouse came as a surprise.

"We feel like we're almost being blindsided," she said.

Her department has meetings set up with concerned parents in the coming weeks, Abernathy said, but some parents went public with their problems before bringing them to the school system.

The county spends about $50 million on salaries, benefits, supplies and programs to serve about 8,600 Hamilton County students who qualify for some special education services or accommodations. That's about 20 percent of the county's 42,000 public school students.

But those figures include 2,257 students in gifted programs and 1,600 more with learning disabilities who usually are cared for in regular classrooms.

Not all families have had problems. Even the most vocal of recent critics have said that they also have many positive stories of caring teachers and wonderful programming that led to marked improvements in their children.

At last week's commission meeting, one parent even praised the special education department.

"These people probably ended up at County Commission because of a lack of response," said Jerry Jensen, president and CEO of the Siskin Children's Institute, a nonprofit that provides research, health care, education and services to children with special needs.

But if the concerns of parents aren't dealt with soon, they could escalate, leading to potential involvement by state or federal agencies or even lawsuits, Jensen said.

"And that's not in anybody's best interest," he said. "There's really no reason to have to go down that path."

Fraley said he has purposely kept lawyers out of it and has made an effort to work out his problems through proper channels.

He insists he's not trying to make the county look bad. In fact, he's been impressed with his daughter's teacher, who for two years fostered significant improvement in the child. That's why he was so stunned and upset with the teacher's removal from the classroom.

Now, he's encouraged that the superintendent is examining his situation. But he said the problem has become much larger than just his concerns about his daughter's education, with parents of special-needs students coming forward from several different schools.

"I think we have an opportunity to step forward and say, 'You're right. Maybe some of these things aren't being done in the best interest of these special ed kids. Maybe we could create a better system,'" Fraley said.

•••

Fraley and Smith spoke for a couple of hours in just one of their conversations last week. Fraley appreciated the time and consideration. But he was struck by the superintendent's own stories of raising a daughter with special needs.

One of Smith's 32-year-old twin daughters has cerebral palsy. Fraley's 14-year-old has multiple diagnoses, including cerebral palsy.

"He knows that I know what he's going through," the superintendent said in an interview.

And Smith's own experiences as a parent have informed his decision-making in the superintendent's office.

For instance, he is adamant that he will not discuss issues of special education students in large, public venues -- like the County Commission chamber. Having felt uncomfortable as a parent in special education group meetings in the past, Smith said he's now much more keen to work through issues with parents privately.

While he knows what it means to parent a child with special needs, Smith questioned the methods of parents who have shown up at commission.

Smith said his office has heard few complaints from special education parents. And board members hadn't heard about the problems before last week's public meetings.

For parents who have concerns and feel they have exhausted options at the school and central office, he said he's willing to investigate.

"But we've got to know where the problems are," Smith said. "We can't expect to get those from the news. We need to get those firsthand from the parent."

Smith also knows from experience that parents won't always get the answers they want. And he said he won't let parents dictate school decision-making.

Even with the recent hubbub, Smith said he trusts the school district's special education staff. That too, has something to do with his own experiences as a parent.

"I know how they do business. I was a parent myself in Hamilton County Schools," Smith said. "My daughter was a student here, graduated here. I have confidence in them."

And if nothing else, the shared experience might be one thing Fraley and Smith can build on.

"This is my role for life," Fraley said. "He and I on some level are in the same boat."