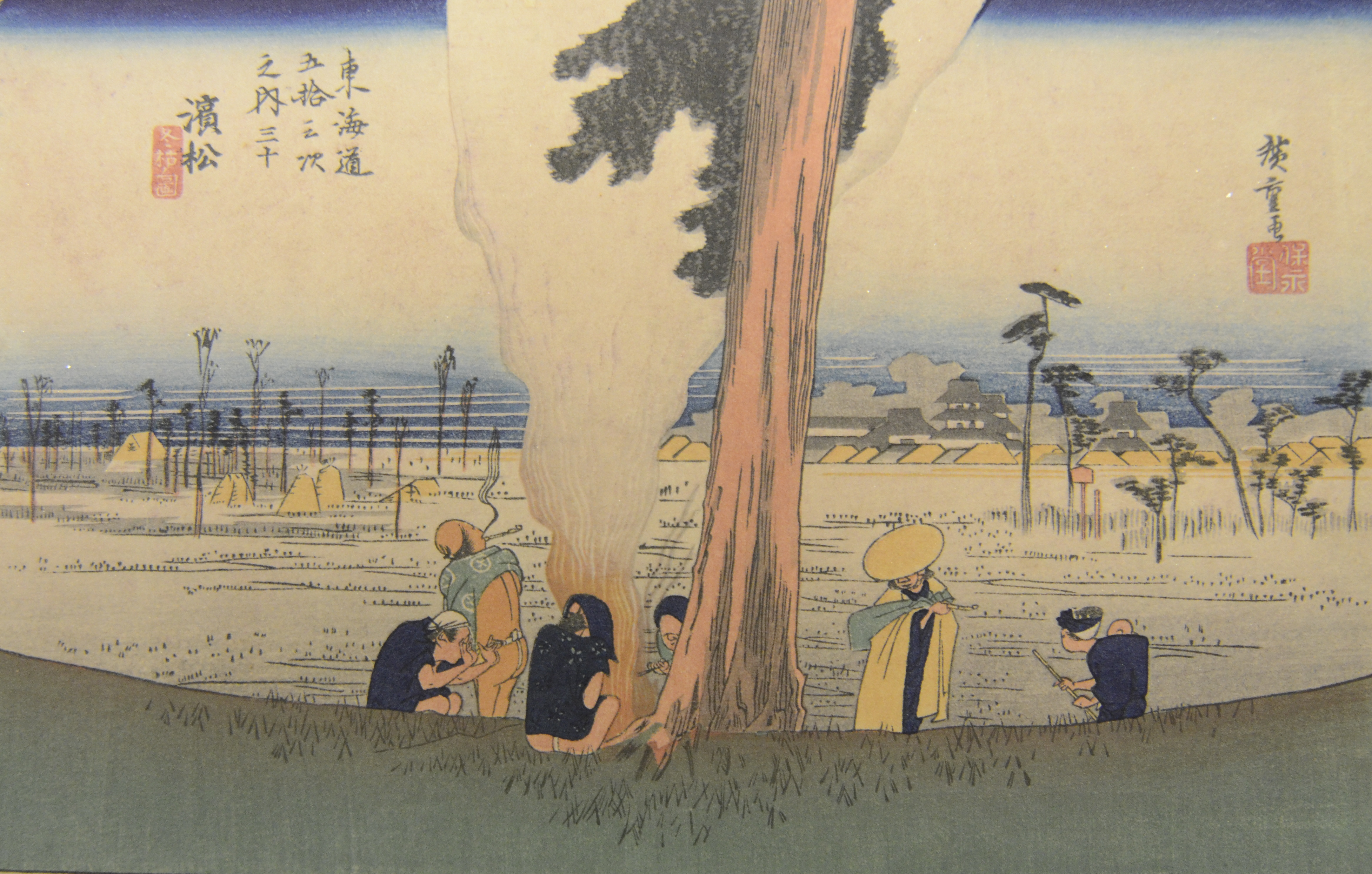

MYSTERY ARTWORK1. Unknown Asian artistUntitled (Landscape with panda), ink on paper2. Unknown Asian artistUntitled (Landscape), ink on paper3. Unknown Asian artistBlue and red porcelain plates on stand, late 18th-early 19th century4. Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III) 1786-1864Portrait of a Courtesan, circa 1859Colored woodcut5. Eishi HosodaCourtesan Kisekawa from the House of Matsubaya, c. 19th century, woodblock image6. Unknown ArtistPair of 20-inch-high Asian vases, ormolu mounted, polychrome enamel, covered7. Ando Hiroshige? (1797-1858)Hamamatsu Station on Tokaido RoadEmbossed wood print8. Margaret Traherne (1919-2006)Vandyke, circa 1972Stained glass window

Around 1859, the Japanese artist Utagawa Kunisada made a graceful woodcut print of a woman kneeling in a flowing blue kimono, head bent over a scroll of parchment.

Last year, the portrait was pulled out of its acid-free folder in the storage rooms of the Hunter Museum of American Art and examined, as the museum weighed whether to remove the print from its collection.

What happened in the roughly 150 years in between?

It's unclear -- the story of the portrait of the woman in the blue kimono is lost. No one on the museum's staff -- past or present -- is sure how long the print has lain tucked away in the Hunter's storage chambers, or how it got there in the first place. There is no paper trail. On the folder that held it, the labels for "Donor" and "Date" are blank.

The portrait of the Japanese woman is one of eight pieces of long-stored art for which the Hunter is trying to fill in the blanks. The museum is trying to find the owners of the pieces, which it has stored for more than 20 years.

"We've never really been forced to do this before. We have a folder on every single item in our collection," said chief curator Ellen Simak. "This is an exceptional situation."

The mystery pieces include a motley collection of Asian ink drawings, ornamental plates, a woodblock portrait and a pair of large porcelain vases.

The Asian artwork is joined by a large stained glass window made by British artist Margaret Traherne in 1972.

The works likely entered the museum sometime before the Hunter defined itself as a specifically American art museum, says Simak.

When the museum was founded in 1951, it featured art from a wider swath of eras and nationalities. It's probable that several, if not all, of the pieces were actually donated to the museum, but records either were never made or were lost.

KEEPING TABS

The questions of the artwork's history bubbled up as Simak and other museum staff started the process of "deaccessioning" -- removing artwork from the museum's collection -- last year.

The museum has about 5,000 drawings, sculptures, paintings and other pieces in its growing collection. Some no longer fits in with the museum's mission, and so it can be cleared out and sold to make room for more.

That process is rare; Hunter hasn't deaccessioned since the 1990s, says Simak. Museums have strong guidelines directing deaccession.

"Collection stewardship requires planning, resources and professional acumen to ensure the maintenance of a dynamic collection that supports the museum's mission," guidelines from the Association of Art Museum Directors spell out. "Deaccessioning is practiced to refine and enhance the quality, use and character of an institution's holdings."

Any profits from a work that is sold must be used only for acquiring other art -- never for operating funds, the association says. Original donors or their heirs should be consulted, if possible.

What if, in a case like Hunter's, that isn't possible?

Tennessee has a law to deal with such dilemmas. The Tennessee Cultural Property Abandonment Law requires museums to give public notice and wait 65 days before they legally acquire ownership of the property in question.

If no one comes forward in the Hunter cases, Simak says the museum will pursue selling the pieces. She does not know the value of the artwork.

"We are not deaccessioning because of value," she said. "They just don't belong in the collection anymore."

Hunter officials say they are working with a lawyer to determine what exactly will help them determine proof of ownership if anyone comes forward to claim the pieces.

Meanwhile, the museum's current standards for recordkeeping seem almost Draconian.

Today, the museum has layer upon layer of recordkeeping. There are receipts filed for each artwork that comes through the doors. Museum registrars create a file and identification card for each piece, plus photos. All the information is compiled in an electronic inventory.

But each step is crucial to avoid finding more mystery artwork 20 years from now, Simak says.

"Do we have any more pieces like this in storage right now?" she says, raising her eyebrows. "Oh, I hope not."

Contact staff writer Kate Harrison at kharrison@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6673.