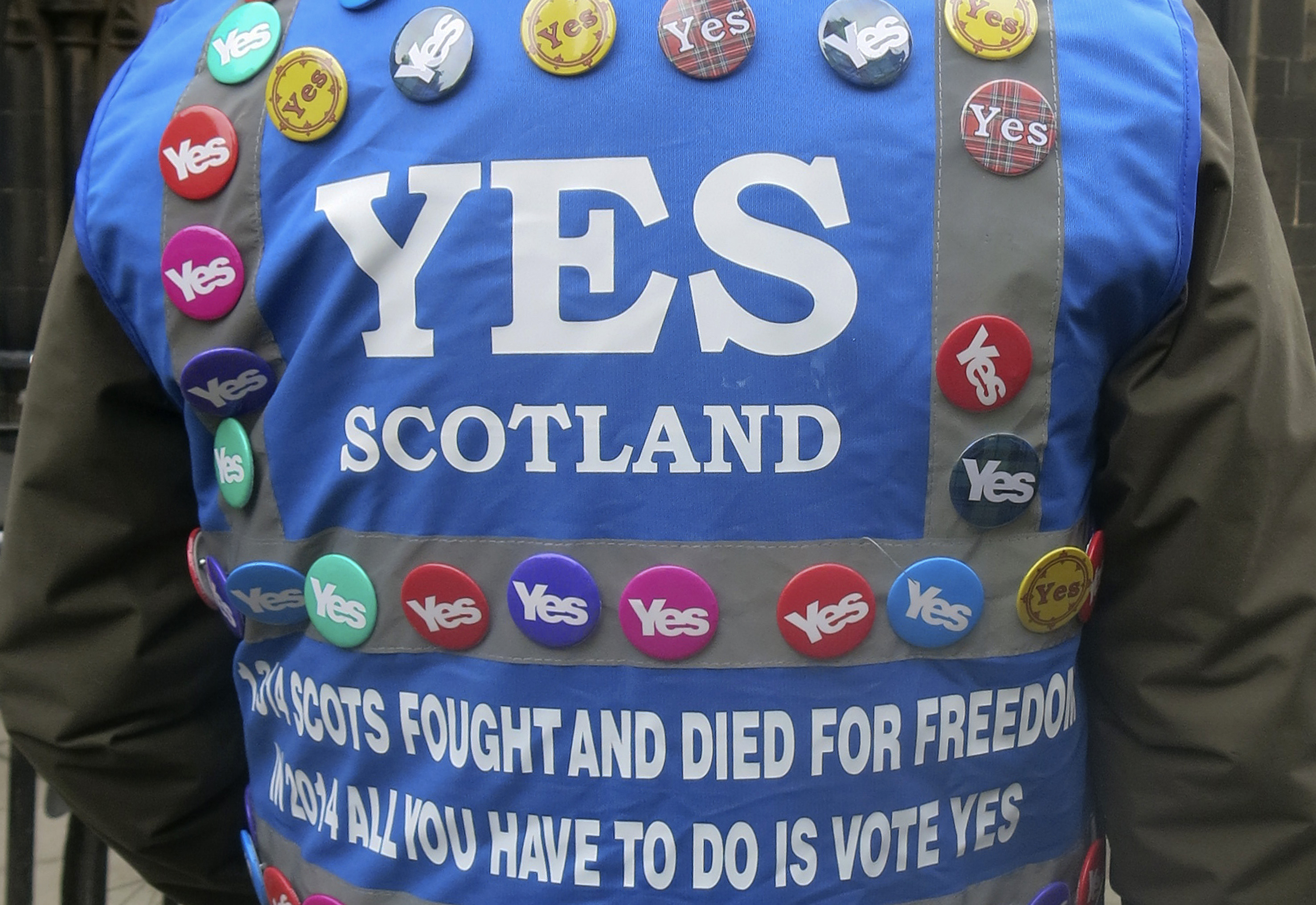

A man wears a multitude of "yes'"campaign badges during a pro-independence march in Edinburgh, Scotland, for the upcoming vote on Scotland's independence from the United Kingdom. Scotland's swithering "middle million" has Britain's future in its hands. "Swithering" means wavering, and it's a word you hear a lot in Scotland right now. Six months from Tuesday, Scottish voters must decide whether their country should become independent, breaking up Great Britain as it has existed for 300 years. Faced with the historic choice, many find their hearts say "aye" but their heads say "why risk it?" Polls suggest as many as a quarter of Scotland's 4 million voters remain undecided, and their choice will determine the outcome. Many long to cut the tie binding them to England, but fear the risks - and the financial fallout.

A man wears a multitude of "yes'"campaign badges during a pro-independence march in Edinburgh, Scotland, for the upcoming vote on Scotland's independence from the United Kingdom. Scotland's swithering "middle million" has Britain's future in its hands. "Swithering" means wavering, and it's a word you hear a lot in Scotland right now. Six months from Tuesday, Scottish voters must decide whether their country should become independent, breaking up Great Britain as it has existed for 300 years. Faced with the historic choice, many find their hearts say "aye" but their heads say "why risk it?" Polls suggest as many as a quarter of Scotland's 4 million voters remain undecided, and their choice will determine the outcome. Many long to cut the tie binding them to England, but fear the risks - and the financial fallout.EDINBURGH, Scotland - Scotland's swithering "middle million" has Britain's future in its hands.

"Swithering" means wavering, and it's a word you hear a lot in Scotland right now. Six months from Tuesday, Scottish voters must decide whether their country should become independent, breaking up Great Britain as it has existed for 300 years.

Faced with the historic choice many find their hearts say "aye" but their heads say "why risk it?" Polls suggest as many as a quarter of Scotland's 4 million voters remain undecided, and their choices will determine the outcome.

Many long to cut the tie binding them to England, but fear the risks -- and the financial fallout.

"I'm swithering a bit," said Sarah Kenchington, an artist from Balfron in central Scotland.

"It's getting really right-wing down in England and it would be quite a good thing to separate from that. But then, politics can be quite a temporary thing -- and this is a very permanent split."

Overcoming such doubts is the challenge faced by Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond and the "Yes Scotland" independence campaign backed by his Scottish National Party. Salmond has appealed to Scots' patriotic hearts, painting the referendum as a choice between starkly different economic and social models: English austerity and Scottish social democracy.

Salmond is critical of Britain's budget-cutting, Conservative-led government, and says an independent Scotland will follow a different path, using its resourcefulness and North Sea oil revenues to create a dynamic economy and a strong social safety net.

He says Scotland will be a "northern light" to balance the "dark star" of London's economic and political dominance -- a vision that strikes a chord with many Scots.

"I'm just looking forward to a different kind of government that has the interests of the Scottish people at heart," said Jeannette Wiseman, an art student from Oldmeldrum in northeast Scotland. "I think the Scottish people deserve a government they vote for. We've ended up with a Conservative government we didn't vote for."

The anti-independence campaign, backed by Britain's three main national political parties, stresses the uncertainties an independent Scotland would face. It warns businesses will flee and thousands of shipbuilding jobs for the Royal Navy will head south. Scots will forfeit the pound currency and could face passport checks at the English border.

Britain could even lose its nuclear-power status if Salmond carries through with his threat to evict the country's fleet of nuclear-armed submarines from their base at Faslane in western Scotland.

Salmond dismisses such warnings as scaremongering, and has even compared the situation to the conflict over Crimea. He said Sunday that the British government's threats to Scotland meant it forfeits the "moral authority" to criticize Russia and the region's snap referendum.

Heated rhetoric is nothing new in this debate. The Scottish and English have always had a complicated relationship -- and long memories. In June, Scotland is planning a 700th-anniversary reenactment of the Battle of Bannockburn, in which Scottish King Robert the Bruce defeated the army of England's Edward II.

The two countries united in 1707 to form Great Britain, with a shared monarch, currency, and a London-based government.

It has always been a lopsided relationship -- England's population is 10 times Scotland's 5.3 million.

But opponents of independence stress that Scotland already has considerable autonomy, with its own parliament, established in 1999, and separate legal and educational systems.

They wonder how independent Scotland will afford to fund schools, universities, health care and social programs, and accuse Salmond of glossing over difficult details. He says Scotland will remain a member of the European Union, but EU leaders have said the country could face lengthy negotiations to get back into the bloc. Edinburgh and London disagree on what share Scotland should get of Britain's North Sea oil money -- and of its trillion-pound national debt.

"I think the Yes campaign is largely based on emotion," said Murray Ogston, a retired accountant from Edinburgh. "I'm a passionate supporter of Scotland, but I think it's a step too far.

"At the moment we have the best of both worlds. We're part of a bigger entity in the U.K., but also have a large degree of control over our own affairs."

Most polls show the anti-independence side ahead by 10 points or more, and long-term trends suggest only about a third of Scots are firmly committed to independence.

University of Edinburgh history professor Tom Devine said the No side's negative campaigning had dented support for independence. He said a warning from British Treasury chief George Osborne that an independent Scotland wouldn't be able to keep using the pound -- as Salmond has long promised -- had exposed the lack of a "plan B in the nationalist camp."

But Devine said the pressure could backfire. "Scots don't like to be bullied, and especially don't like to be bullied by creatures like Osborne," an aristocratic Conservative from the south of England.

Despite its poll lead, the No campaign is nervous. Salmond is a canny leader who is widely regarded as Britain's most skillful politician. The Yes side also has a strong grassroots campaign that is targeting younger voters through social media and music gigs.

Ironically, the preferred option of many voters is a compromise that's not on the ballot -- more autonomy, but not full independence.

Cameron endorsed that idea last week, saying "a vote for 'No' is not a vote for 'no change.'"

But there will only be two options on Sept 18: In or out. Few people are willing to predict the outcome.

"The Yes campaign's narrative, its aspirations, its aims, really do speak to many aspirations and disgruntlements that Scots have had in recent decades," said John MacDonald, director of the Scottish Global Forum think-tank.

"The polls consistently point to a No vote, but I wouldn't be surprised to see a Yes vote."