The battle for the future of civil liberties and law enforcement funding will be fought with words as weapons.

Civil forfeiture -- the program that allows the government to seize and keep property of people accused of crimes -- stirs police, prosecutors, lawmakers and civil rights experts to sling verbal arrows pro and con.

Some attack a program that can cost owners their property even if they're never convicted of a crime. Others defend it as a deterrent, a way to make people think twice before breaking the law.

But in Georgia, there's no way for one side to triumph because neither has statewide data about civil forfeiture. Neither side can provide concrete facts to support their arguments.

Next year, though, the weapons will be sharper. The Georgia Legislature unanimously passed a civil forfeiture reform bill this session that requires the state's law enforcement agencies to announce every time they take stuff from a citizen.

By the end of every January, the agency will have to post a form online showing what items they seized in the previous year, what crimes the property owners were charged with and how the agencies used the items they took.

Members of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Institute for Justice say this law will let them gather data from every law enforcement agency in the state, crunch numbers and prove their key point: Civil forfeiture lines law enforcement's pockets with cash at the expense of poor people, usually minorities.

If they can prove that, these civil rights groups will pressure lawmakers to weaken the police's power to seize property, if not kill civil forfeiture outright.

"You needed to have this," said Marvin Lim, a lobbyist for the ACLU of Georgia. "Otherwise, nothing was going to get passed."

Law enforcement leaders say they will use the data to prove that civil forfeiture is necessary. Advocates argue that rather than preying on poor minorities, civil forfeiture attacks rich leaders of criminal enterprises.

"This is the most effective crime-fighting tool we have in our state," said Terry Norris, executive director of the Georgia Sheriffs' Association. "People don't get prison time anymore. They serve probation. This is the one thing that makes a difference to criminals. You take their assets, you have hurt them."

Will it work?

Researchers already are supposed to have access to statewide forfeiture data. In 2010, the Legislature passed a law mandating that a report from each agency "shall be electronically transmitted" to the University of Georgia's Carl Vinson Institute for Government website.

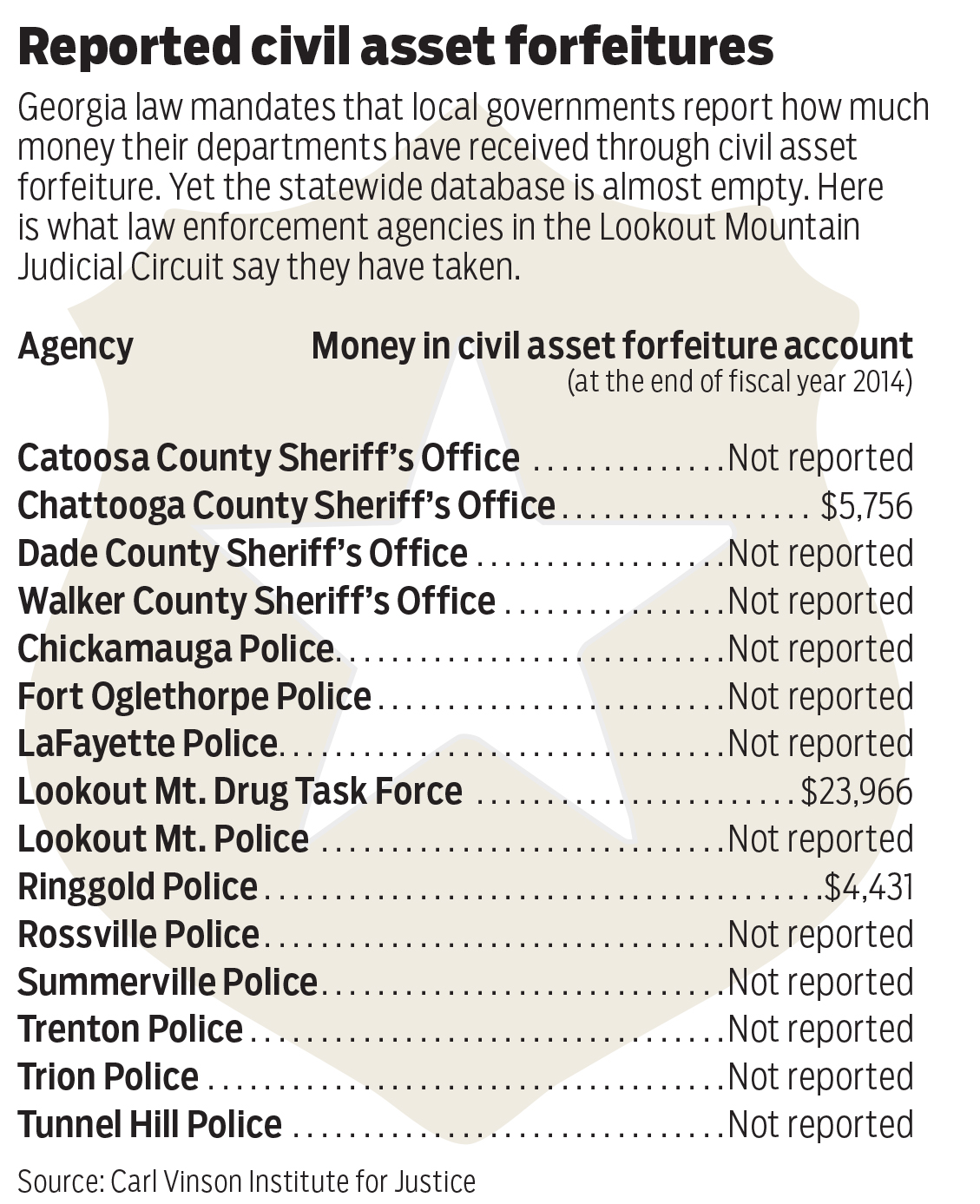

But few reports are actually available there. For example, there are 15 law enforcement agencies in the Lookout Mountain Judicial Circuit, but only three civil forfeiture reports on the website.

Police say the current law is vague -- it doesn't say who is supposed to upload the report, just that somebody has to do it.

Catoosa County Sheriff Gary Sisk and Walker County Sheriff Steve Wilson said they didn't post their report online. Instead, they gave them to their local commissioners' offices when they submitted budget applications, as mandated by a separate law. Both believe the commissioners' offices were supposed to post them online.

The new bill clarifies the process, putting the burden on the police agency. To help agencies remember, the law says that if the reports aren't on the website within 60 days of the deadline, the agency legally cannot seize any more property.

What happens next?

Critics of civil forfeiture hope to use statewide data to reduce police use of the program. A similar effect happened in Minnesota earlier this decade.

In 2010, the Minnesota Legislature passed a bill requiring agencies to provide details about every use of civil forfeiture. Two years later, a state auditor revealed that the average seizure was worth only $1,200.

Lee McGrath, legislative counsel for the Institute for Justice, believes Georgia lawmakers will see similar data.

"That revelation will be different from the myth that seizures and forfeitures are only used on large criminal syndicates," he said.

Last year in Minnesota, legislators passed a bill saying police can't keep forfeited property unless the accused person is convicted of a crime. McGrath wants a similar law passed in Georgia.

He also wants to shift the burden of proof with the program. Right now, prosecutors have to prove by "a preponderance of evidence" that the seized property is connected to a crime, like any other civil case. McGrath wants the prosecutors to prove this beyond a reasonable doubt.

Norris, of the Sheriffs' Association, said the burden of proof standard has been upheld in several court cases to be constitutional. If the law were changed, people would challenge it, creating several more court cases.

"There was no need, in the opinion of the sheriffs and prosecutors, to change," he said.

Contact staff writer Tyler Jett at tjett@timesfreepress.comor at 423-757-6476.