Dr. Raymond Brown was outstanding - too outstanding, as it turned out, for his own good.

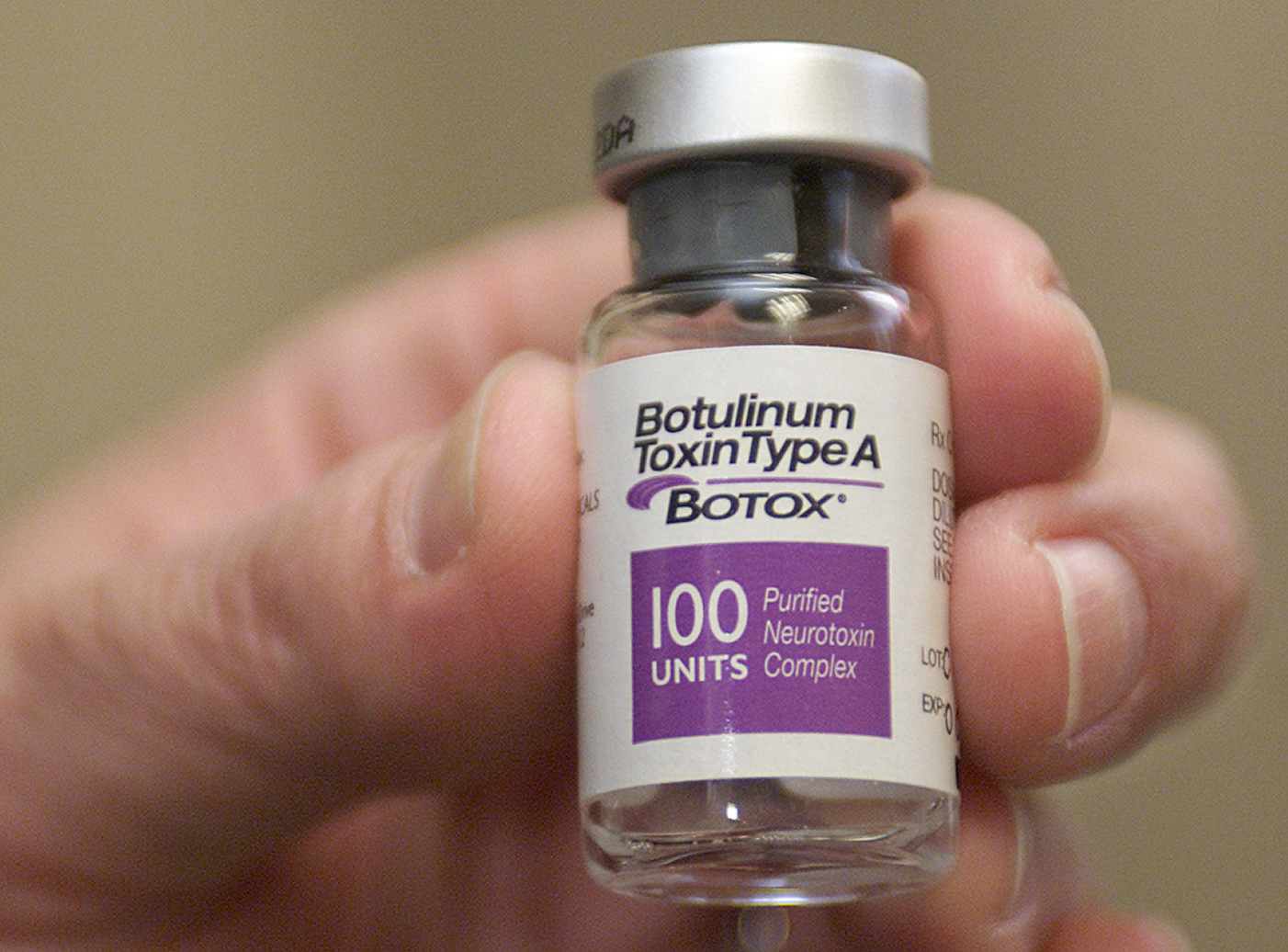

A fraud investigator for the federal Department of Health and Human Services' Office of the Inspector General, while searching a computer database to see which doctors billed Medicare the most for Botox injections, found the Cleveland, Tenn., doctor's name right at the top.

Brown billed Medicare for 17,000 vials of Botox in one year, the most of any doctor in the United States.

Federal investigators did the math. If the doctor had seen one patient every 15 minutes for 10 hours every day for six days a week, he still wouldn't have used 17,000 vials.

When they obtained a search warrant and checked the doctor's office, they discovered he had actually only purchased 254 vials of Botox, according to Richard Haines, special agent in charge of the Nashville office of HHS' Office of the Inspector General.

Brown pleaded guilty to defrauding Medicare and was sentenced last year to 20 months in prison. The government was able to seize $6 million from his bank account as reimbursement for the fake billings, Haines said.

No one seems to know how much health care fraud by medical professionals costs U.S. taxpayers and consumers. But given that overall health care expenses are estimated at around $3 trillion each year, fraud accounts for at least several billion dollars. The U.S. government recovered $2.4 billion in judgments in health care fraud cases in 2015, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. In Tennessee alone, fraud investigators recovered $38 million, and no one is suggesting they caught all of the wrong-doers, because they are hard to detect.

Unlike conventional thieves, doctors and other medical professionals who steal use the click of a mouse instead of a gun or knife.

How does it work?

Doctors may bill for services that were never performed, as in Brown's case. In another case, investigators used a hidden camera to prove that a Tennessee social worker who billed the government for 30 minutes of counseling was often spending only five minutes with patients. She was sentenced to probation and ordered to repay $80,000.

Or doctors or hospitals will bill for services that were not needed. In one of the most-watched local cases, the Justice Department is accusing Cleveland, Tenn.-based nursing home giant Life Care of instructing staffers to perform unneeded physical therapy on nursing home patients and padding bills to Medicare by millions of dollars. Life Care has denied the charges.

In April, two lab professionals from Bristol, Tenn., were convicted of health care fraud in a scheme involving urine tests for substance abuse treatments. If the patients were paying their own bills, they were charged $25 and given a simple test, prosecutors claimed. But if they were covered by Medicare, Medicaid or private insurance, they were told they needed additional, more expensive tests. The total bill for unnecessary tests was more than $14 million, prosecutors said.

Fraud charges are also a weapon in the law enforcement crackdown on so-called "pill mills" that prescribe addictive painkillers for people who do not need them and who often re-sell them illegally. The Justice Department in late March charged a Lenoir City chiropractor and a doctor of osteopathy from Manchester with prescribing unneeded pills and then billing Medicare and TennCare.

Another type of fraud involves listing a procedure incorrectly in order to get reimbursement from an insurance company. Instead of listing a nose job as plastic surgery, for example, which isn't covered by insurance, a doctor records it as surgery to repair a deviated septum, which is covered.

The fight against health care fraud is a joint effort among private insurance companies and the state and federal government. In Tennessee, the feds have five investigators based in Nashville, working for HHS's Office of the Inspector General, as part of a team of 34 staffers spread across the Southeast. They handle Medicare cases.

Since Medicaid is delivered through the states, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation has its own Medicaid Fraud Control Unit, with seven offices throughout the state (including two investigators in Chattanooga). The staff of 39 includes 24 investigators, a nurse, a computer programmer and two auditors.

Both the OIG and the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation work with fraud units at BlueCross BlueShield and other private insurers. BlueCross BlueShield has a staff of seven investigators, checking into private health insurance claims as well as Medicaid claims, on behalf of the state.

The insurance companies are on the front line, taking in complaints via a hotline, phone calls, or emails, or their own investigations.

Often a complaint starts with the consumer, who gets a notice in the mail explaining what his or her health insurance paid for.

"Somebody calls us and says they got an Explanation of Benefits. 'It says a doctor saw me on this date - I didn't see the doctor,'" said William Benson, manager of the Special Investigation Unit at BlueCross BlueShield. "Sometimes we've found out they didn't get the service and that was abuse or fraud, or sometimes it's a billing error."

One of the most powerful weapons investigators have are whistleblowers, medical staffers who turn in their bosses for fraud. Under federal law, they can receive a portion of any cash settlement against their employer.

For example, a nurse who worked for Alive Hospice was awarded $263,000 last September after reporting that Alive was over-billing Medicare and TennCare. Alive paid the federal government and the state of Tennessee more than $1.5 million to settle the case.

Whistleblowers are particularly useful because they can provide insider information as to who gave the orders to perform a particular activity, making it easier for investigators to determine if the problem was a one-time-only incident or something that was done repeatedly and in more than one facility.

"We rely on the goodness and honesty of practitioners out there, who when they come across something will come to us and tell us what they have been asked to do," said Norman Tidwell, the special agent in charge of the TBI's Medicaid Fraud Control Unit.

Investigators often look for how closely a doctor was working with a facility such as a pain clinic or home health care service which is billing Medicare or Medicaid.

"They are being paid as medical director for a home health care company and all they are doing is signing orders for patients they never see and with whom they have no legitimate patient relationship," the OIG's Haines said.

Fraud investigators all emphasize that most doctors and medical professionals are honest.

"The vast majority of providers are trying to do the right thing," said BlueCross BlueShield's Benson. "We're talking about a small minority of players out there who can make everybody look bad."

Investigators know they are not catching all of the fraud.

"I believe we do make an impact, but unfortunately there is enough of it out there that it keeps us extremely busy," said OIG's Haines.

What is baffling to Tidwell is why some medical professionals commit fraud.

"You have a physician making $350,000 legitimately and yet he wants to bill for another $200,000 he is not entitled to," he said. "That's a hard pill to swallow."

Contact staff writer Steve Johnson at 423-757-6673, sjohnson@timesfreepress.com, on Twitter @stevejohnsonTFP, or on Facebook, www.facebook.com/noogahealth.