Payments to professionals*

Scroggins & Williamson: $1.2 millionGuggenheim Securities: $1.1 millionGreenberg Traurig: $990,000Hunter, Maclean, Exley & Dunn: $860,000Ronald Glass: $515,000GGG Partners: $470,000Healthcare Management Partners: $430,000GlassRatner: $360,000*Approved Thursday

What providers are owed (and what they are offered)

CHI Memorial Hospital: $490,000 ($115,000)Parkridge Medical Center: $285,000 ($65,000)Erlanger Health System: $250,000 ($60,000)Serve You Custom Prescription Management: $200,000 ($45,000)Hamilton Medical Center: $170,000 ($40,000)

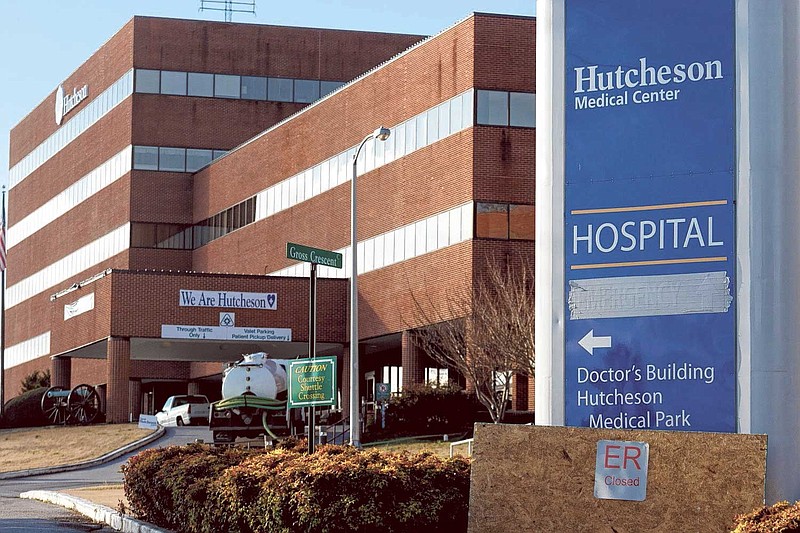

In the rubble left after Hutcheson Medical Center's crash, nobody who worked with the hospital is getting what they're owed.

But the lawyers and financial experts who guided Hutcheson through its final days are getting a better deal than the hospitals that treated Hutcheson's employees. How much better? Almost four times as much.

On Thursday, a bankruptcy court judge approved the final payments for seven law firms, financial advisers and a trustee who handled the hospital's final preparations before an Atlanta company bought Hutcheson in May. Combined, the groups are getting about $6 million - 90 percent of what they are owed.

Compare that to a deal the bankruptcy court judge approved earlier this month for the health care providers that treated Hutcheson's employees. While those groups submitted bills for about $2.8 million, they will split $650,000. That is 23.4 percent of what they're owed.

The disparity comes down to leverage. Also, some help from the U.S. Congress, which created laws dictating which types of workers get paid first. Typically, lawyers and financial advisers are close to the front of the line.

Farrell Hayes, Hutcheson's CEO through its final days, criticized the arrangement, saying he pushed the lawyers to set aside more money for health care claims. In December, when Hayes lost his job, many Hutcheson employees had been turned over to collection agencies, asking for the money that the hospital's self-insured plan wasn't covering.

"It is beyond hypocritical that [bankruptcy trustee Ronald] Glass pays himself millions while refusing to pay the employee health care claims," Hayes wrote in an email Thursday.

Glass did not pay himself millions, as a judge approved a plan that gave him $515,000 and his company another $360,000.

Rob Williamson, one of Hutcheson's bankruptcy attorneys, said the lawyers and financial consultants were vital to salvaging what they could from the hospital. For example, they brokered a deal with a company in New York to buy Hutcheson's nursing home.

"We would have had to shut down the nursing home and ship 110 elderly, frail residents into other nursing homes and close the nursing home at the time if there wasn't a mechanism to make sure the professionals were compensated to keep things moving," he said.

"That's just the way it is," Williamson said. "That's how these Chapter 11 [bankruptcy] cases are able to go forward."

Usha Rodrigues, who teaches corporate law at the University of Georgia, agrees: The bankruptcy system is set up to benefit lawyers and other financial experts more than most people. She said that is a market force. There needs to be an incentive to bring these people to the table, and they won't work hundreds of hours on a case like this without knowing they will get paid well, she said.

"It looks bad, right?" Rodrigues said. "The lawyers get paid, and these people don't get paid. That's just a harsh result of bankruptcy."

Spokespeople for Erlanger Health System and Parkridge Medical Center, two of the companies looking at the 23.4 percent deal, declined to comment for this story.

Why does it work like this?

In a bankruptcy case, the first groups to get paid are usually secured creditors. These are companies that have some documents guaranteeing them some sort of payment. For example, Hutcheson owed Regions Bank $26 million.

As part of a loan, Regions had the legal right to foreclose on Hutcheson's ambulatory surgery and cancer center, get payments from insurance providers for work done at Hutcheson and foreclose on another 65 acres of Hutcheson property. That is, of course, if Hutcheson couldn't pay Regions back the $26 million.

When Hutcheson filed for bankruptcy, Regions held a higher position than most other creditors - the ones without any sort of legal documents guaranteeing them payment. Those are unsecured creditors.

But even among that group, there is a pecking order, which is supported by a federal law. The bankruptcy judge doesn't have wiggle room to change that order without the creditors' approval. The group with the first priority are people waiting for some sort of domestic payment - single mothers needing child support, for example.

That group didn't exist with Hutcheson's bankruptcy. The next group did, though: The lawyers and financial advisers who helped the bankruptcy process flow. Federal lawmakers gave these people such a high priority because, without them, a bankruptcy case like Hutcheson's would never move forward.

"They're supposed to get some sort of incentive," said Summer Chandler, a bankruptcy law professor at Georgia State University.

Where do the health care claims fit?

Under federal law, health care claims are usually the No. 5 priority, meaning they will get a smaller cut of Hutcheson's money. But Hutcheson's case is slightly more complicated.

Hutcheson is self-insured, but the hospital's administrators fell behind on paying employees' health care claims before filing for bankruptcy in November 2014. By how much? About $2.2 million, according to bankruptcy court records. (Multiple former employees have said an employee of the U.S. Department of Labor is now investigating exactly how that happened.)

But after filing for bankruptcy, Hutcheson fell behind on health care claims by another $650,000. Chandler said that chunk of the payment would probably be considered an administrative expense like that of the lawyers - because this $650,000 is part of the money required for Hutcheson's day-to-day business.

So the $2.2 million before November 2014 doesn't have a high priority. But the other $650,000 does. That may be why Regions agreed to "carve out" $650,000 for health care claims.

Health care providers have received the 23.4 percent offer. If the provider agrees to the deal, the provider can no longer pursue money from former Hutcheson employees - some of whom say debt collectors are still waiting for their money even though they were supposed to have insurance.

Contact staff writer Tyler Jett at 423-757-6476 or tjett@timesfreepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @LetsJett.