KRAKOW, Poland (AP) - When Pope Francis arrives in Poland this week for World Youth Day, he will meet a nation still deeply committed to its conservative Catholic traditions and to the memory of St. John Paul II, who inspired this country's successful struggle against communism in the 1980s.

But Francis will also find a nation under international censure for backtracking on some of its democratic gains, and a clergy deeply entwined with a ruling right-wing party that analysts say is out of sync with his philosophy of humility and mercy.

"The (Polish) Church is a bit uneasy about this visit," said philosopher of religion, Zbigniew Mikolejko. "On one hand it would like to use the visit to strengthen its importance. On the other hand it is anxious because Francis' attitude is radically different from that of the Polish Church leaders, who want to have authority over the people's conscience and to have real power."

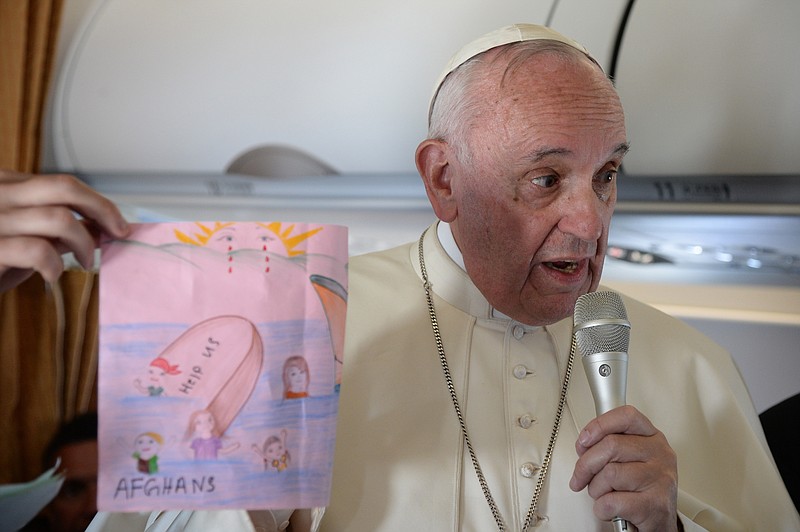

Francis will find himself even more at odds with the nation's political leaders, who have shut the doors to refugees from the Middle East and Africa, arguing they need to ensure Poland's security. Ruling party leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski, though Catholic, warned last year that migrants arriving in Europe are a danger because they carry "parasites and protozoa." Messages like those mark a stark contrast to appeals by Francis for Europeans to welcome people fleeing war in the Middle East. The government is also at odds with Francis on climate change, bowing to Poland's powerful coalmining lobby. On the other hand, it has taken steps to help families and the poor, aligning with Francis' priorities in that area.

The attitude of Poland's church, with a focus on doctrine, its attempts to fight Western secular values and its support for the ruling party's polices, has repelled some of the faithful.

"We think that only we, in the lay, pagan Europe have preserved a vibrant Christianity," Father Leon Wisniewski, a Dominican Friar, recently wrote in an article critical of the Polish church in the progressive Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny.

Francis is coming to the heart of this faith, to Krakow, in southern Poland, where the Rev. Karol Wojtyla served as priest and bishop before becoming John Paul II. Through Sunday, Francis will be holding meetings with hundreds of thousands of young people as they celebrate World Youth Day, an event launched by John Paul.

But Francis may not be able to avoid the issues of Poland's political and church life: his very first meetings after arrival Wednesday at Krakow's John Paul II airport are with Poland's President Andrzej Duda and with the bishops, at the historic royal Wawel Castle and at the Wawel Cathedral, which holds relics of St. John Paul II.

Poland' Catholic Church recently celebrated 1,050 years of Christianity in Poland, marked by the baptism of a medieval king, a crucial religious and political event that tied the nation to Rome and to Latin, Western culture.

Over 90 percent in this nation of 38 million declare themselves as Catholic, though not all are regular churchgoers. The Church enjoys a special position because of the key role that it played in preserving the nation's identity and culture during almost two centuries of partitions, two world wars and through decades of oppressive communist rule, when there was no independent political power in Poland.

Under these circumstances, many Poles equate being Polish with being Catholic, which can have troubling implications for ethnic and religious minorities in the country.

"Linking Catholicism to being Polish is an obstacle that prevents us from taking a respected place among the European nations which are pluralistic," Wisniewski wrote in Tygodnik Powszechny.

Poland's traditional attachment to the Church and to religion is something that Francis is well aware of.

"You are a nation that throughout its history has experienced so many trials, some particularly difficult, and has persevered through the power of faith, upheld by the maternal hands of the Virgin Mary," the pontiff said in a televised message to Poles last week. "I am certain that my pilgrimage to the shrine of Czestochowa (on Thursday) will immerse me in this proven faith and do me so much good."

In a vivid sign of the nation's attachment to the Church, Poland's leading adventurer and explorer, Marek Kaminski, will scale one of the highest peaks in Poland's Tatra Mountains, Giewont, with stone slates bearing the Ten Commandments and will unfurl the World Youth Day's flag as Francis flies overhead into Poland on Wednesday.

Poland's Catholic Church has long been a player in Poland's political life but this status grew in last year's presidential and general elections, when it encouraged the faithful to support Poland's traditional Catholic values, against European liberalism. That contributed to the victory of the pro-Church Law and Justice party, whose members declare attachment to Catholicism and listen to the bishops in their social policy.

In recent months, Prime Minister Beata Szydlo has praised a civic initiative aimed at a total ban on abortion and has introduced bonuses to encourage couples into having many children. In his recent message to Poland, Francis praised its pro-family policy.

But the government also turns a blind eye to church services being offered to far-right nationalist organizations, whose motto often is: "God, Honor, Motherland."

"Many bishops have become ideologues of the ruling party," Mikolejko, a professor at Poland's Academy of Sciences, told The Associated Press.

But that will herald trouble for the Church when the party eventually loses power, he said.

The Church also risks being drawn into the government's conflict with its opponents in Poland and with some Western leaders and institutions over the Constitutional Tribunal, a top court recently paralyzed by the ruling party's efforts to gain control of it. Some Western leaders have said that Poland's rule of law is threatened and the European Commission has opened scrutiny procedures, while tens of thousands of Poles have marched against the government's policy.

"To many Poles the Church is no longer a spiritual leader, though years ago, under communism, it was the mainstay of truth and justice," Wisniewski wrote in the Catholic weekly.