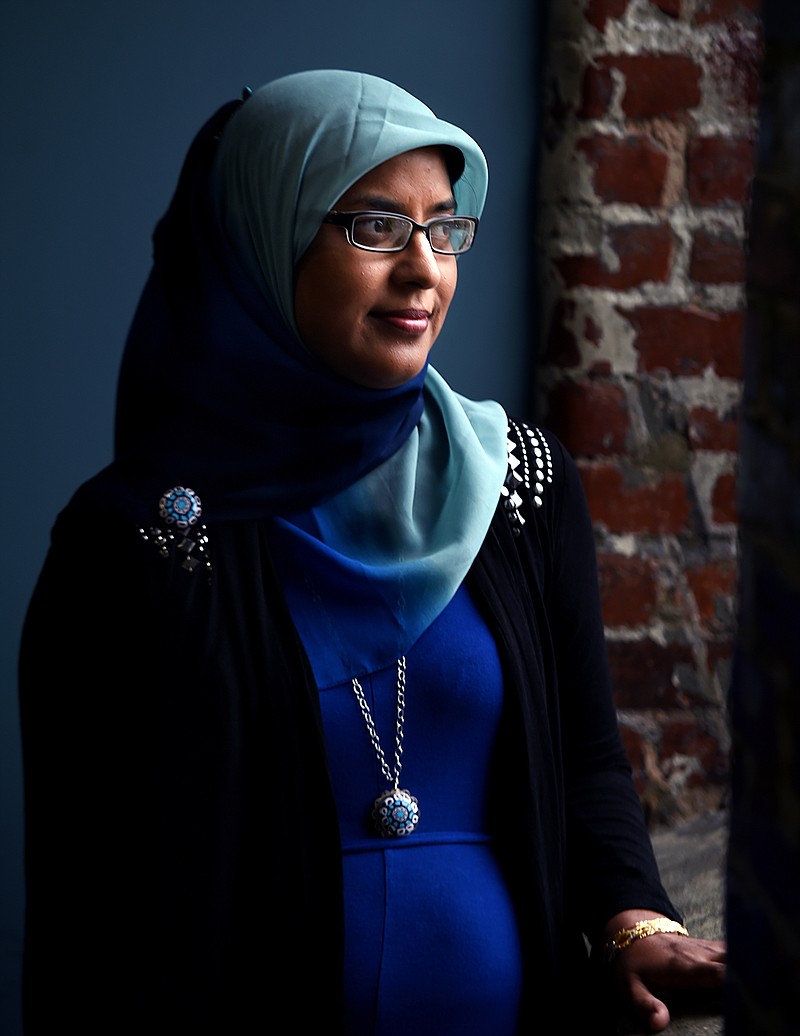

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) - Dozens of jeering protesters faced down Sabina Mohyuddin at a community meeting, but she stood strong at the podium.

Mohyuddin, in a clear, firm voice, told the crowd in Manchester that Muslims often face disrespect, vandalism and violence in Middle Tennessee.

"In 2007," she said, "a mosque was burned down in Columbia, Tennessee."

Many in the crowd erupted into cheers.

"Shame on you!" she fired back, loudly.

Mohyuddin, wearing a scarf around her head, continued with her presentation at that meeting two years ago, keeping her voice loud to be heard over the heckling.

She wasn't afraid or even agitated: U.S.-born Mohyuddin, 43, has been standing up to people for most of her life - even her mother.

Her parents are from Bangladesh and were brought together in an arranged marriage. They came to the U.S. so her physician father could do his residency.

Mohyuddin wasn't always a fighter. As a child, she remembers standing out as a brown girl in a white school, the now-closed Brookmeade Elementary School in Belle Meade.

"In December all the kids are singing Christmas songs and I'm lip-synching," she said. "I met Jewish kids who said they did the same."

"I didn't want to say anything. I don't want to be that one kid who's complaining."

But her Islam faith was strong: She remembers praying together as a family every night, and her father reading from the Koran.

"I would never schedule something that I would miss that evening prayer. If a friend said, 'Let's watch a movie,' I'd say, 'That's during sunset prayer. I can't go.' "

Despite piety, the women in her family never wore scarves or hijabs that many Muslim women do to signal modesty.

Her mom didn't wear one, her aunts in Nashville didn't wear them, even most of her family in Bangladesh didn't wear scarves. There was a notion that educated women didn't wear hijabs.

Just before sixth grade, Mohyuddin's family visited friends in Missouri, and a girl Mohyuddin's age wore a scarf to school. Mohyuddin was entranced by the guts that took.

"That floored me," she said. "You're going to have to explain everything; you'll be questioned about it. I saw her and the courage it took."

Mohyuddin was a pretty modest girl anyway, often wearing long sleeves and long pants to school, so that aspect appealed to her. Plus, Mohyuddin's maternal grandmother wore a scarf.

So, when Mohyuddin went to John Trotwood Moore Middle School in Green Hills, she did so wearing a scarf.

"It felt right, it felt natural, and if I'm doing something to please God, then I'll be at peace."

One person who resisted the move: her mother, who ironically, helped give Mohyuddin the confidence to wear the scarf because she has worn a sari every day she has lived in the U.S.

But her mother asked her daughter not to wear the scarf to school.

That awakened her inner rebel: "Somebody tells me what to do, I don't listen."

"I try to do what's right. If I'm doing what I think is right, I don't care what anyone else thinks."

And that's why Mohyuddin became a Muslim activist, and more than 20 years later, found herself at a 2013 community meeting in Manchester, facing down anti-Muslim activists.

It happened just after a Coffee County commissioner posted a Facebook cartoon of a man with one eye looking down the sights of a shotgun, with the caption, "How to wink at a Muslim."

The U.S. attorney for the area called the meeting to talk about hate speech and to try to better relations between Muslims and Christians.

Instead, anti-Muslim protesters from outside the area showed up and turned the meeting combative.

"It was a circus," Mohyuddin said.

She was particularly on edge because the man who has run the Islamic Center of Columbia, Daoud Abudiab, was in the audience.

When Mohyuddin declared the mosque had been set on fire and the people cheered? She snapped.

"They're cheering and he's right there. That's why I said, 'Shame on you.' Do they understand there are real people involved here?

"Sometimes people need to be told things to their face."

___

Information from: The Tennessean, http://www.tennessean.com