In the 19th century, the Mississippi Valley suffered a number of yellow fever epidemics. Named for a jaundicing of the victim's skin, the disease caused fever, chills, hemorrhaging, severe pains and, near the end of life, a black vomit.

Its cause was unknown until after the Spanish-American War when it was discovered to be mosquito-borne. Waves of infection frequently came to New Orleans from the Caribbean or West Africa and spread up the Mississippi River with the river traffic.

Memphis was struck in 1828, 1855, 1867 and 1873. The last episode caused an incredible 2,000 deaths in the Bluff City. A combination of a mild winter, long springs and hot summers set the stage. The pestilence usually raged until the first frost of fall suppressed the mosquitoes.

In late July and early August of 1878, Memphians were once more afflicted. In the space of two weeks, about 25,000 people fled the city. Of those remaining, more than 5,000 died. Despite efforts at quarantine, Tennessee towns along the various rail lines leading out of Memphis were stricken. Germantown, Moscow, Milan, Collierville, Paris, Brownsville, Martin and LaGrange all had large death rates.

Like many other communities, Chattanooga citizens sent financial aid to the stricken areas. Local health care workers volunteered to go, and some heroically died.

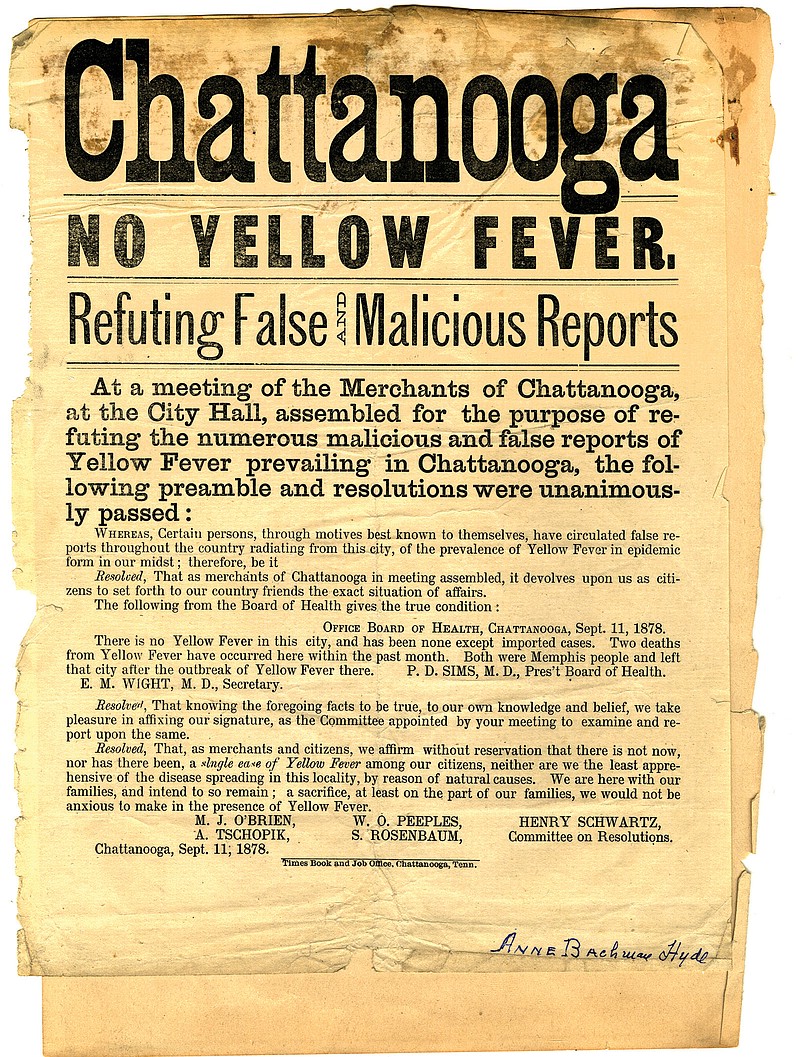

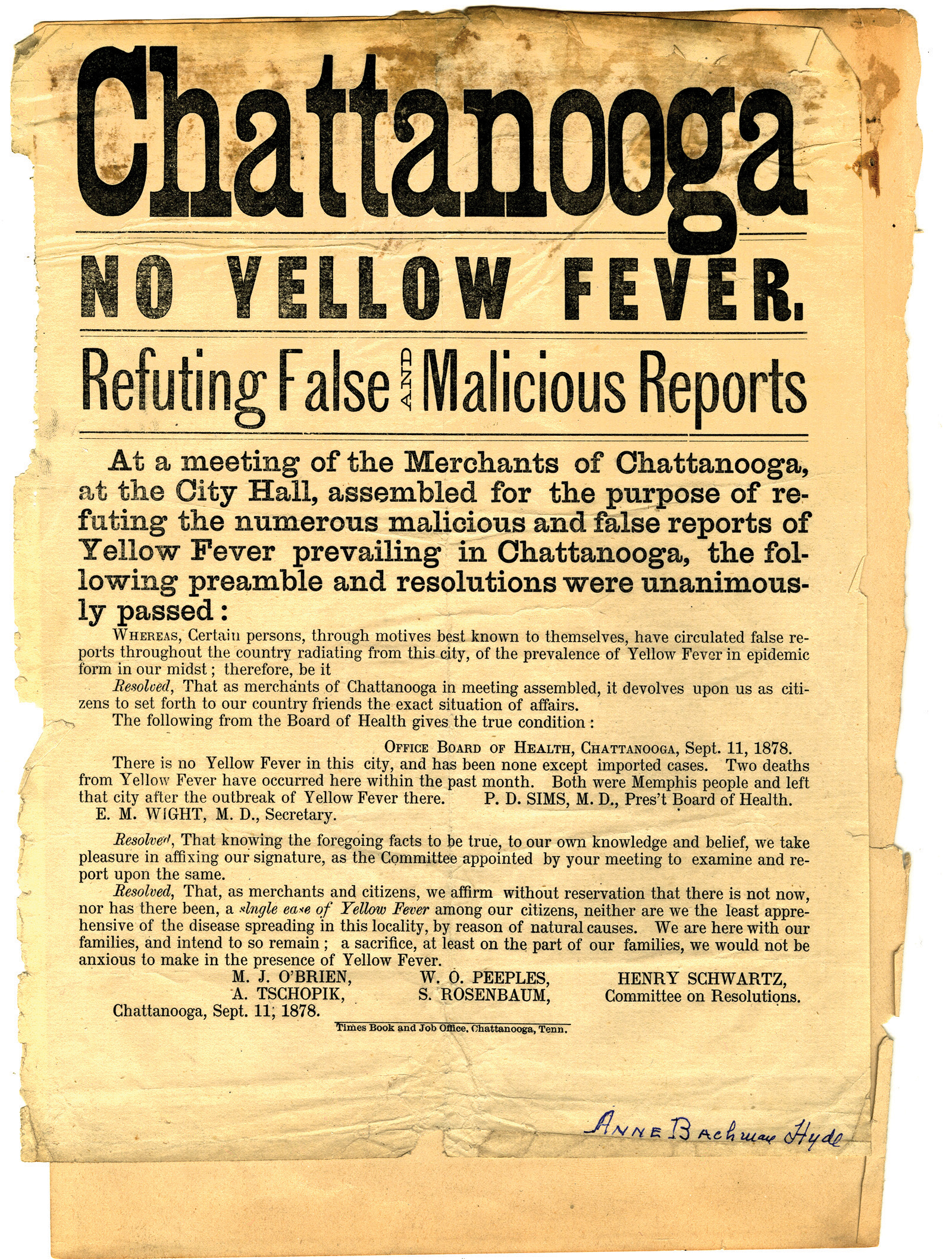

On Aug.14, 1878, Jeanette Swartzenburg arrived in Chattanooga from Memphis. Three days later, she fell sick and died. Another Memphis refugee, William Griffin, was stricken on Sept. 3 and died Sept. 6. Both were staying in a low-lying area, south of Eighth Street and west of Market. Notwithstanding these deaths, rumors of yellow fever in the city were belittled in The Chattanooga Times of Sept. 17 and 19. Prominent Chattanooga citizen, Mrs. L.H. Corey, died of the fever on Sept. 19, four days after her infant son.

The disease spread rapidly, reaching its fullest extent on the week ending Oct. 11, when 144 new cases were reported. Then 33 deaths came at the end of the following week. Of the city's 12,000 residents, as many as 10,000 fled, some to the tops of Lookout and Signal mountains.

Writing to his father on Oct. 16, 1878, C.S. Crofut described how the disease suspended business in the city and reported that people "are dying like sheep." Essential services began to break down -- there was essentially no fire service and little police protection. Headed by E.A. James, a relief committee of prominent citizens in some ways supplanted the city government and let it be known that looters would be hanged. Slow construction of a gallows seemed to retard the growth of larcenous activity.

Just as Chattanooga had sent aid to other areas, donations came in from near and far. Public-minded citizens donated bread, butter and coal. Several wagonloads of food and 500 chickens came from Soddy. Funds came from as far away as Paris, France, and New York City. Financier J.P. Morgan sent $1,000. The most substantial aid came from Atlanta, which sent doctors, nurses and funds to establish a hospital.

Among those who died tending the sick were the local Catholic priest, Father Patrick Ryan, physicians Dr. R.N. Barr and Dr. Edwin Baird, and a young teacher from Michigan, Hattie Ackerman.

Perhaps the most colorful character who met his doom during the epidemic was Harry Savage, a 35-year old Englishman who made his living as a professional gambler. He opened his home to children left without care due to sick or dead parents and provided them with food, clothing and medicine. Then he too was struck down by the pestilence.

Among the last victims was Mayor Thomas Carlisle, who came to Chattanooga as a Federal soldier. Of Carlisle, who worked tirelessly, Judge Lewis Shepherd wrote that there "was something of the Horatian spirit in these last days of his."

Cold weather eventually broke the epidemic. Although some accounts indicated that the fever killed 366 people in Chattanooga, a careful count showed that there were actually only 140 deaths.

Life returned to normal. The surviving members of the relief committee met for the last time in 1916 to dispose of a small amount left in its treasury.

Local attorney and historian Sam D. Elliott is author or editor of books and essays on Tennessee in the Civil War era. For more information, visit chattahistoricalassoc.org or call LaVonne Jolley at 423-886-2090.