View other columns by Mark Kennedy

Ernest Jackson is like a human slot machine. Shake his hand and stories fall out.

For a few days, I knew Jackson only as a name on a yellow Post-it note taped to my computer. It read: "Ernest Jackson. Army Reserve building grave site. Willow and 23rd streets."

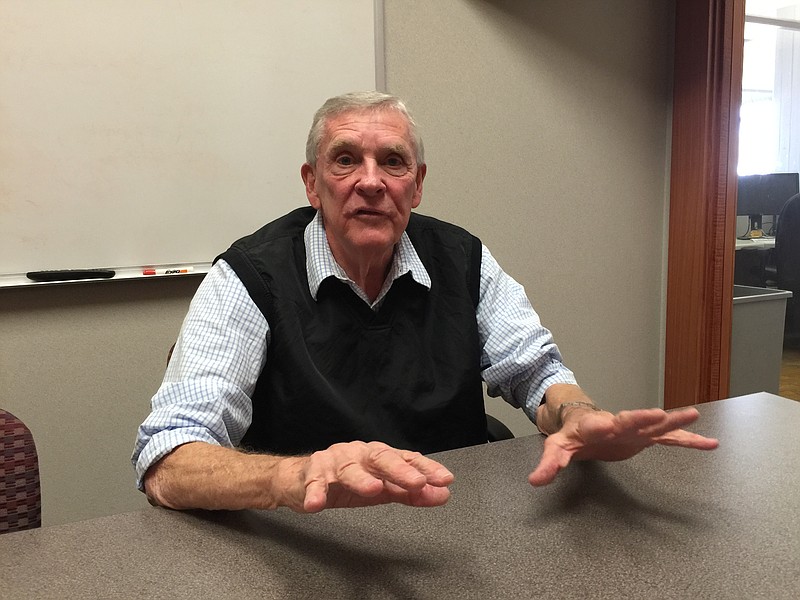

Eventually, we talked and, afterward, I felt like I knew him better than some of my aunts, uncles and cousins. Storytelling is a gift, a dying art really, and Jackson, 76, is a master raconteur.

Every story he tells is followed by an apology. "I hope I'm not boring you," he'll say as a segue to his next vignette. Or, "One more thing, and then I'll shut up."

When he dropped by for an interview one day this week, Jackson launched into the story about a "graveyard" near the intersection of Willow and 23rd streets in the Oak Grove neighborhood.

Only, it wasn't actually a graveyard, he explained. At least not a traditional one. There were no gravestones or markers, only an underground grid of brickwork that Jackson dug up as a boy and associated with dead people.

The kids of Oak Grove had been warned to stay away from the empty field, he said, which their parents told them was the site of an early 20th century pest house - a place where people with deadly contagious diseases were quarantined. A quick search of historic documents shows several mentions of a pest house in Chattanooga, including in the context of a yellow fever outbreak in 1878 and a smallpox scare in 1900.

But once Jackson and I realized the details of the pest house story were likely lost to history, he shifted gears and began telling me random stories about his life.

Somehow, I came to know

' There were 25 boys and four girls in the Oak Grove neighborhood in the 1950s, a ratio Jackson appreciated until he hit puberty. "I was in pig heaven," he said.

Back in the day, the Oak Grove boys played "king of the hill" on a mountain of dirt near the neighborhood playground. One day, Jackson said, he took a borrowed bow and arrow and launch a high-arching shot from the top of the dirt mound that traveled the length of a football field before accidentally hitting a neighborhood boy in the face.

The boy was bloody, but ultimately OK, Jackson remembers, and his parents were only mildly concerned. Today, the story would likely lead local news websites: "Boy hit by arrow in Oak Grove."

Another time he shot a ball bearing out of a steel pipe and disabled a transformer. Another time he stole valve stems off cars in a school parking lot, and later got paddled by the principal as a result.

' One of the boys in the neighborhood was taunted when his parents called him in to practice his piano, Jackson remembers. The boy, Harold Newman, grew up to be president of Shorter College in Rome, Ga.

' Jackson's older brother, Joe B. Jackson, was a football standout at Middle Tennessee State University who later went on to become mayor of Murfreesboro, Tenn. He has a whole boulevard, Joe B. Jackson Parkway, in the midstate named after him.

' Once, Jackson and his young buddies were flying down a hill on bicycles in a local cemetery when he missed a turn and went flying into a gravestone.

A local mechanic straightened out his bike frame with a sledgehammer, and Jackson limped home with his wobbly bike.

' Jackson met his future wife, Marge, while working in the toy department at the old Miller Bros. department store downtown. She was an elevator operator there, and he assembled swing sets.

The two hit it off quickly and their romance intensified when Marge discovered she could stop the express elevator between floors, Ernest explains with a wink.

' On their wedding day, Ernest and Marge stopped at the Teddy Bear Motel in Cleveland, Tenn., but were turned away when the clerk asked for a marriage license and determined that it was unsigned.

Ernest told his bride, "Stay here," and rushed back to Chattanooga to get the preacher's signature.

When you spend time with a natural storyteller, their life stories just sort of spill out in dollops.

Thanks for sharing your memories, Mr. Jackson. To me, our rambling talk was two hours well spent.

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@ timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6645.

Follow him on Twitter @TFPCOLUMNIST. Subscribe to his Facebook updates at www.facebook.com/mkennedycolumnist.